RICHARD NATKIEL

ATLAS OF WORLD WAR II

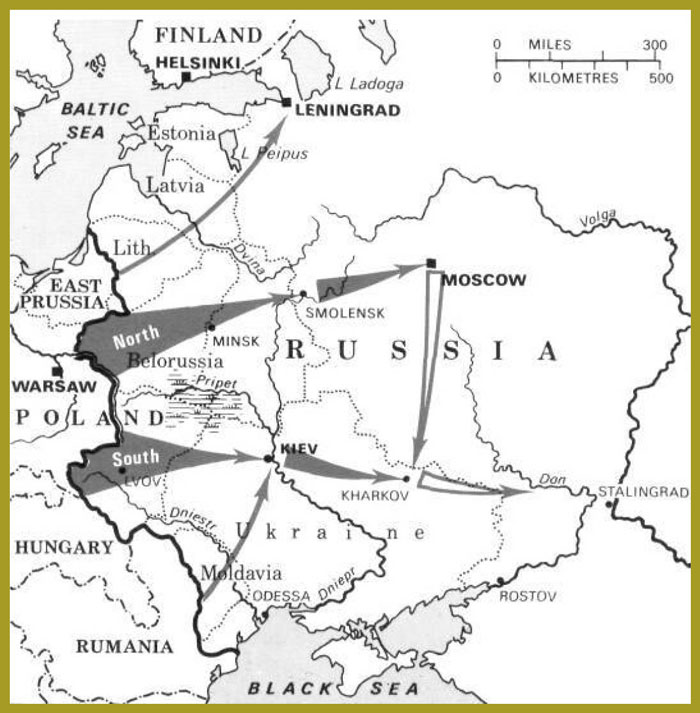

The initial German thrusts to Moscow and Kiev.

A northern attack was later added to the original two-pronged assault plan.

Hitler finally identified Leningrad as the prime target, and it was this plan of attack that was selected.

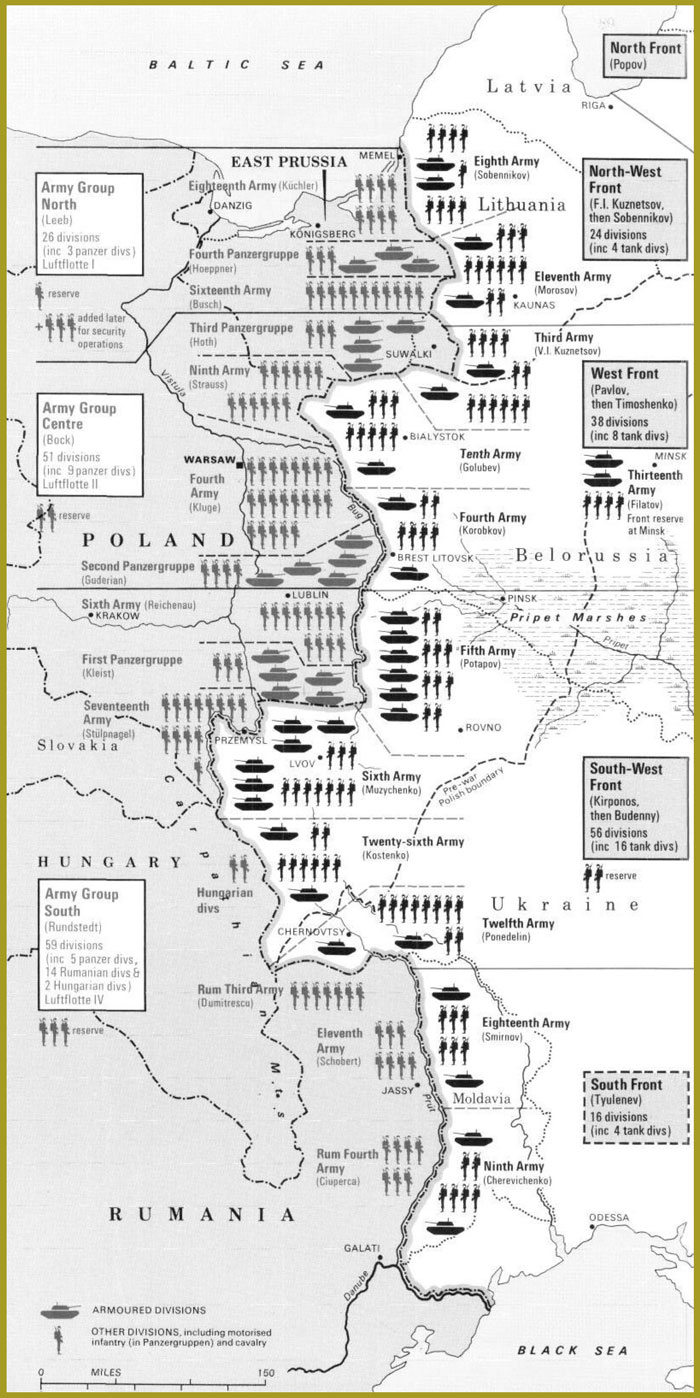

The Eastern Front from the Baltic to the Black Sea, showing the relative strengths and dispositions of the two protagonists.

German forces achieved almost total surprise in their 22 June invasion of Soviet territory, which was preceded by a devastating air attack that all but wiped out the Red Air Force. Fourth Panzer Group took a series of northern objectives that brought it to the Luga by 14 July. Army Group Centre sealed off Russian forces at Bialystok and Gorodische, taking 300,000 prisoners and 2500 tanks in a week's operations. Army Group South faced the greatest resistance in the Ukraine, where the Russian Fifth Army counterattacked on 10 July to prevent an assault on Kiev.

This development incited Hitler to divert Army Group Centre from its attack on Moscow via Smolensk into the Ukraine offensive. Second Army and Heinz Guderian's Second Panzer Group were ordered south to destroy the Soviet Fifth Army and surround Kiev. Guderian was radically opposed to abandoning the Moscow offensive, but he turned south on 23 August as ordered. An unsuccessful Russian counteroffensive failed to halt the German advance north of Gomel, and the Soviet South-West Front suffered heavy losses every time it gave battle. Many divisions were trapped in pockets and destroyed piecemeal, while at Kiev alone, half a million Red soldiers were captured.

By mid November the Germans had seized Rostov and the Perekop Isthmus, which commanded the Crimea. In the center, their victories at Smolensk and Bryansk had enabled them to capture Orel, Tula and Vyazma. The Baltic States had been occupied, and the Finnish alliance had helped open the way to Leningrad.

The crew of a German Panzer attempt to free their tank from frozen mud by lighting a fire.

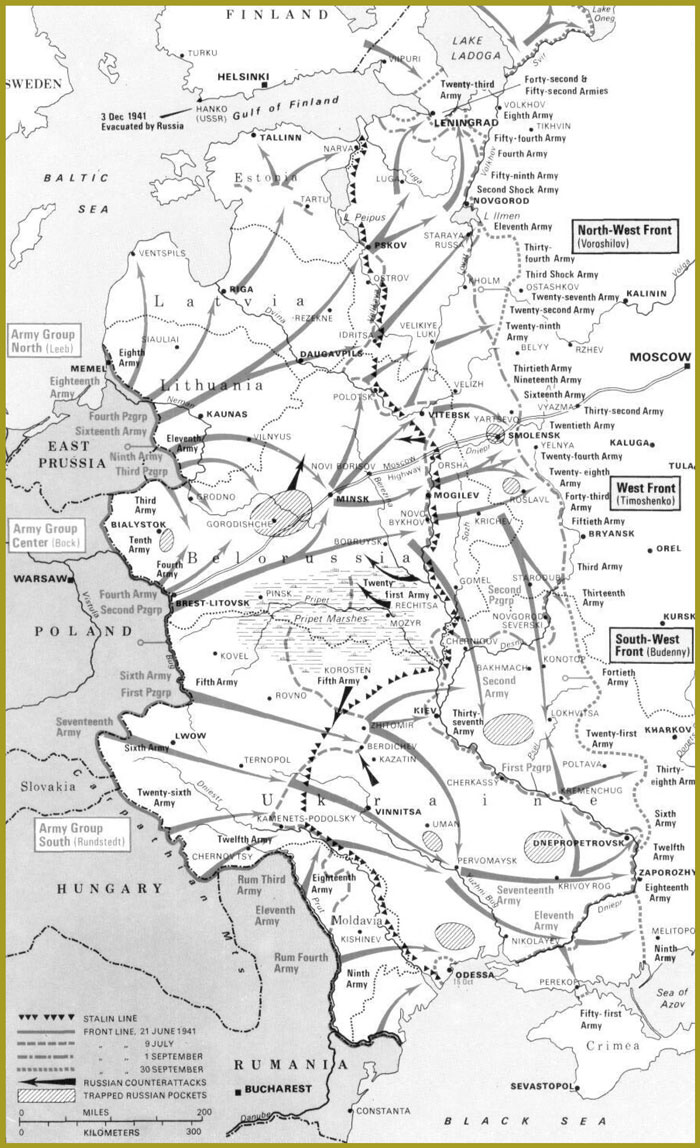

The frontline moves progressively eastwards as German pressure forces Russia to yield.

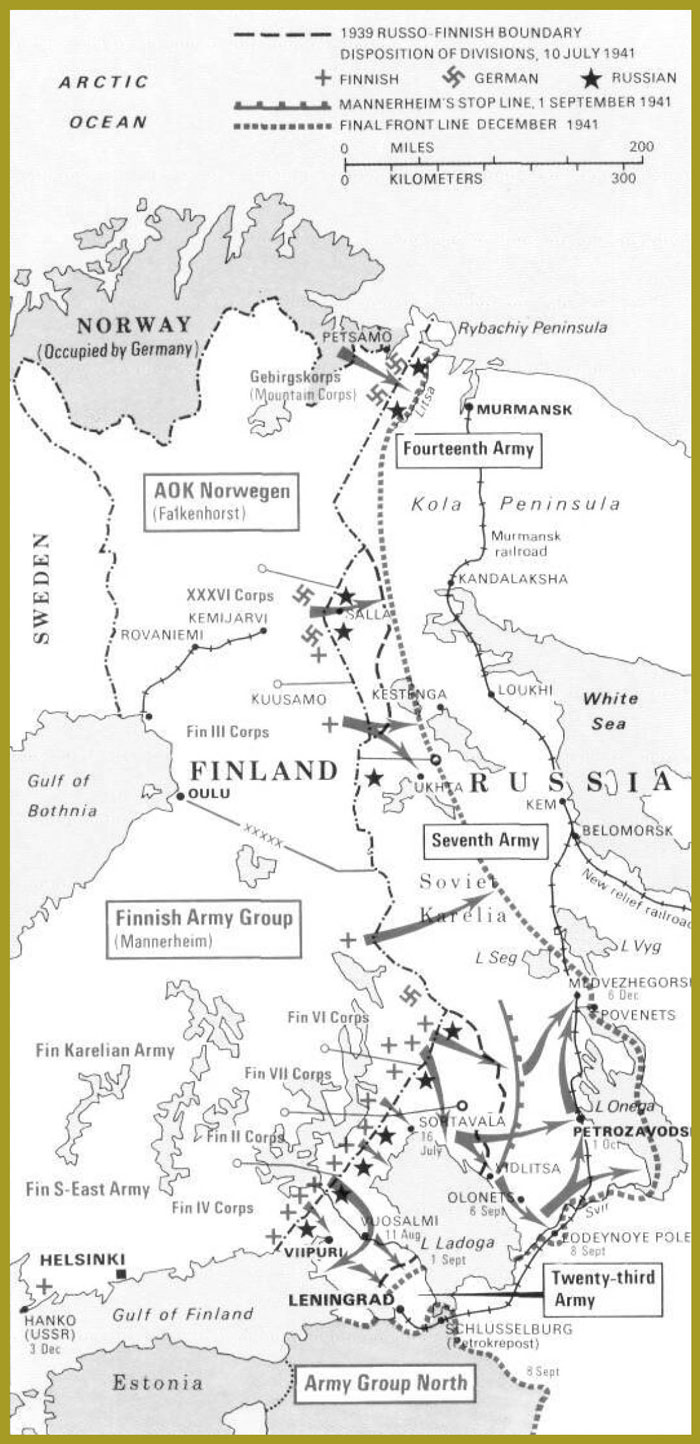

The 1941 alliance with Germany brought significant improvements in Finland's forces. Mobilization and training systems were revamped, as the Finns prepared to regain the territory lost to Russia the previous year by expediting the German assault in the north. Marshal Carl von Mannerheim, hero of the Russo-Finnish War, would lead first the army and then the state for the balance of World War II.

Joint German-Finnish attacks began on 19 June 1941, with early successes around Lake Ladoga. The Russians were outflanked there and began to withdraw by water, until the Finns had pursued to a point near their former frontier (1 September). On the Karelian Isthmus, another attack reached Vuosalmi on 16 August, but was stopped short of Leningrad by a second Russian retreat. At this point Mannerheim called a halt: having regained the territory lost in the previous year, he was reluctant to become more deeply involved in the attack on Russia.

Offensives did not resume until several days later, when attacks north of Lake Ladoga and against the Murmansk railway achieved their objectives. Then the Russian resistance grew increasingly stronger, and by early December the Finns were on the defensive. The front line stabilized along an axis east of the 1939 Russo-Finnish boundary.

With German assistance, the Finns established a front line to the east of their 1939 border.

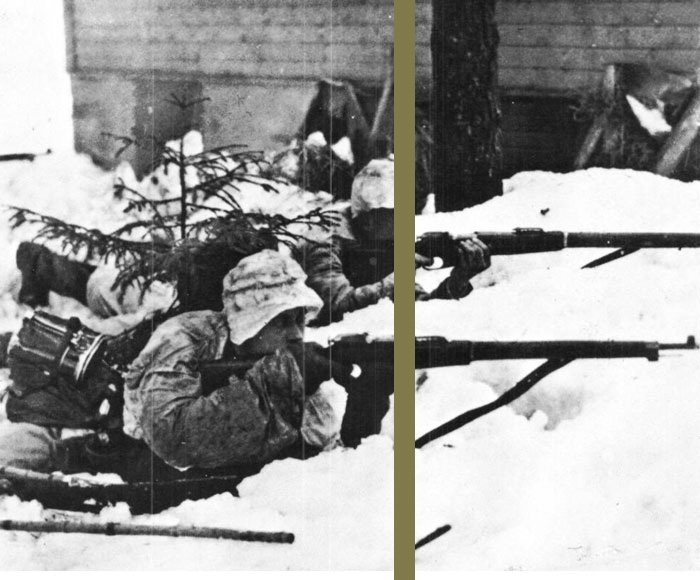

Finnish infantry adopt defensive positions on the Mannerheim Line as Russian pressure increased.

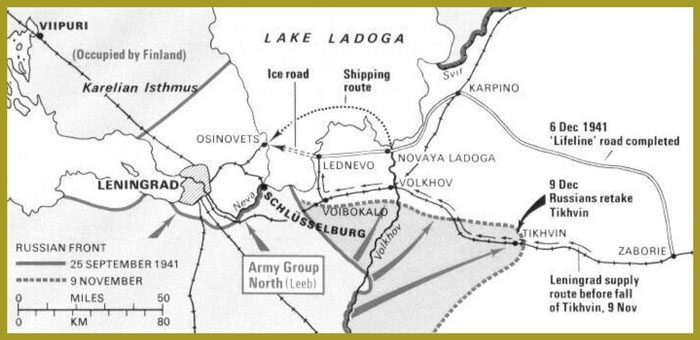

German Army Group North, commanded by General Wilhelm von Leeb, arrived near Leningrad on 1 September 1941. The Germans had decided not to storm the city, but to isolate it and starve out its defenders. Artillery bombardments began immediately, and within two weeks Leningrad had been cut off entirely from overland communication with the rest of Russia.

The city had only a month's supply of food - heavily rationed - and starvation set in by October. The following month, 11,000 died of hunger. Meager supplies continued to come in by barge across Lake Ladoga in the early fall, but on 9 November the Germans took Tikhvin, the point of origin, and ice on the lake made navigation impossible. Four weeks later, the Russians opened a new 'Life line' road from Zaborie to Lednevo, but winter weather and difficult terrain slowed supply trucks to a crawl.

Thousands more had succumbed to starvation in Leningrad by early December, when the Red Army's counteroffensive began to make itself felt. Tikhvin was recaptured, and the Germans were pushed back to the Volkhov River. The Russians repaired the railroad and opened an ice road across the lake, which was now frozen solidly enough to bear the weight of trucks. By Christmas Day, it was possible to increase the bread ration in Leningrad. But relief came too late for many: on that same day, almost 4000 died of starvation.

Supply routes to the besieged city of Leningrad.

Finnish members of the Waffen-SS in action.

Moscow - Strike and Counter strike

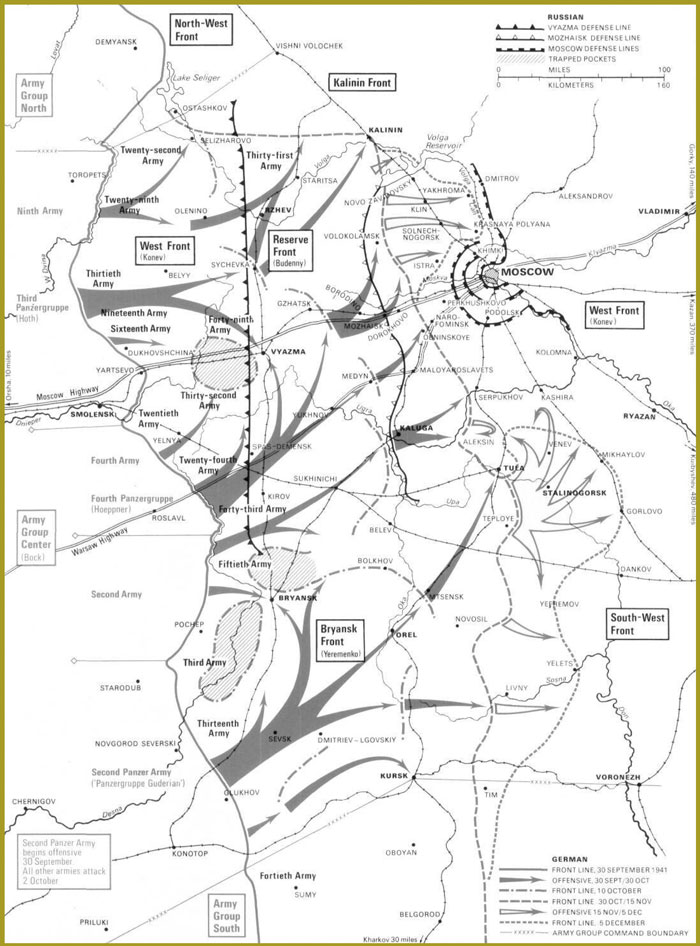

After capturing Kiev, the Germans redeployed their forces for the assault on Moscow. They had a superiority of two to one in men and tanks, three to one in the air. Fourteen Panzer divisions were involved in the attacks that converged on Russia's capital beginning 30 September.

By 7 October large pockets of Soviet troops had been cut off around Vyazma and Bryansk. They were systematically destroyed in the next two weeks, after which heavy rains put a serious check on German mobility. The Mozhaisk defense line offered increasing resistance, and by 30 October German forces had bogged down miles from Moscow. Many men and tanks were lost in the frustrating advance through a sea of mud.

When the weather changed, it did little to help the German cause. The freeze that set in hardened the roads, but German soldiers found it difficult to adapt to the extreme cold, which also created new problems with their vehicles. By 27 November, units of the Third Panzer Group finally reached the Volga Canal, 19 miles from Moscow center, but they lacked the support for a frontal assault on the city. Elements of the Second Panzer Army had gotten as far as Kashira, but they had to fall back for the same reason.

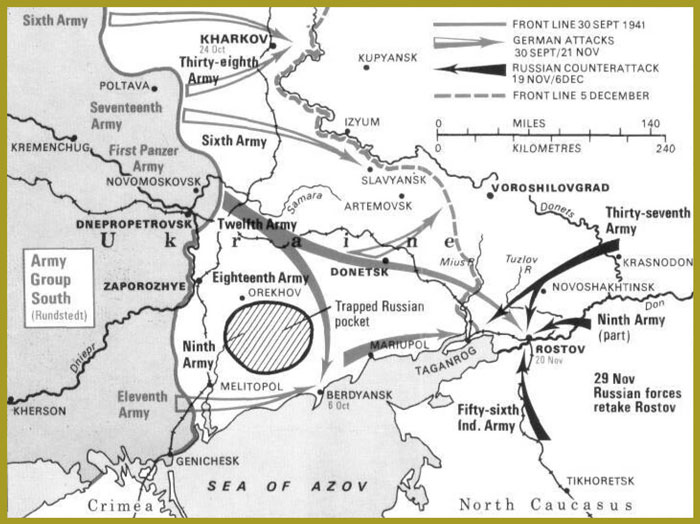

The German Army Group South pushes to capture the Ukraine, but is forced to withdraw to the Mius River.

Muscovites dig defense lines around the capital, 1941.

The German assault on Moscow.

By 5 December the Germans realized that they could go no farther for the time being. Valuable time has been lost in the capture of Smolensk, whose courageous defenders had helped delay the German advance on Moscow until the dreaded onset of winter. Now the capital could not be completely encircled, and heavy bombing did not offset the failure to close Moscow's window on the east. Fresh Soviet troops began to arrive from Siberia even as the Germans faced temperatures that plummeted to 40 degrees below zero.

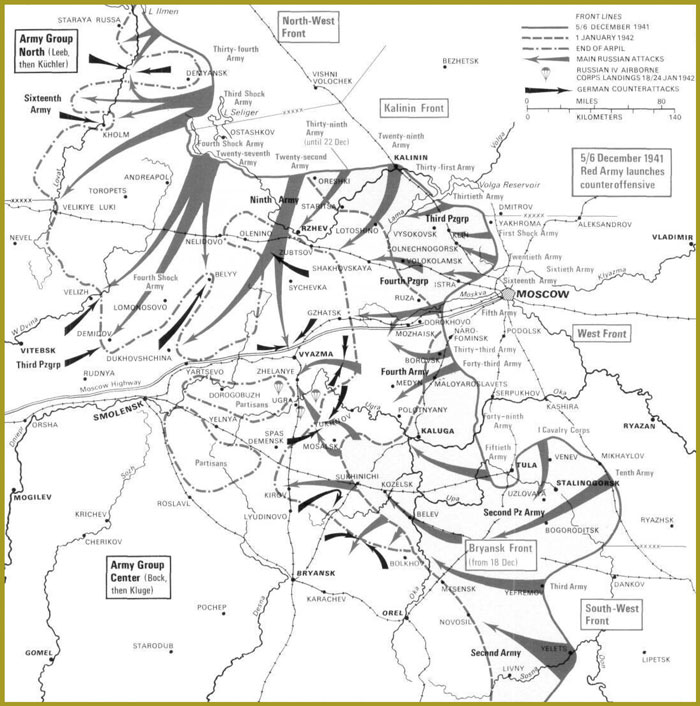

On 8 December Hitler announced a suspension of operations outside Moscow, but the Soviet High Command was not listening. Employing the reserves it had gathered in previous weeks, the Red Army launched a great counteroffensive that recalled the winter of 1812, when Napoleon's forces came to grief on the same ground. Avoiding German strong- points, the Soviets advanced by infiltration-passing over fields instead of roads, making skillful use of Cossack cavalry, ski troops and guerrilla forces. The Germans were harried from flank and rear, forced from one position after another.

Tanks and planes became inoperable in the extreme cold, and supply lines were tenuous or nonexistent.

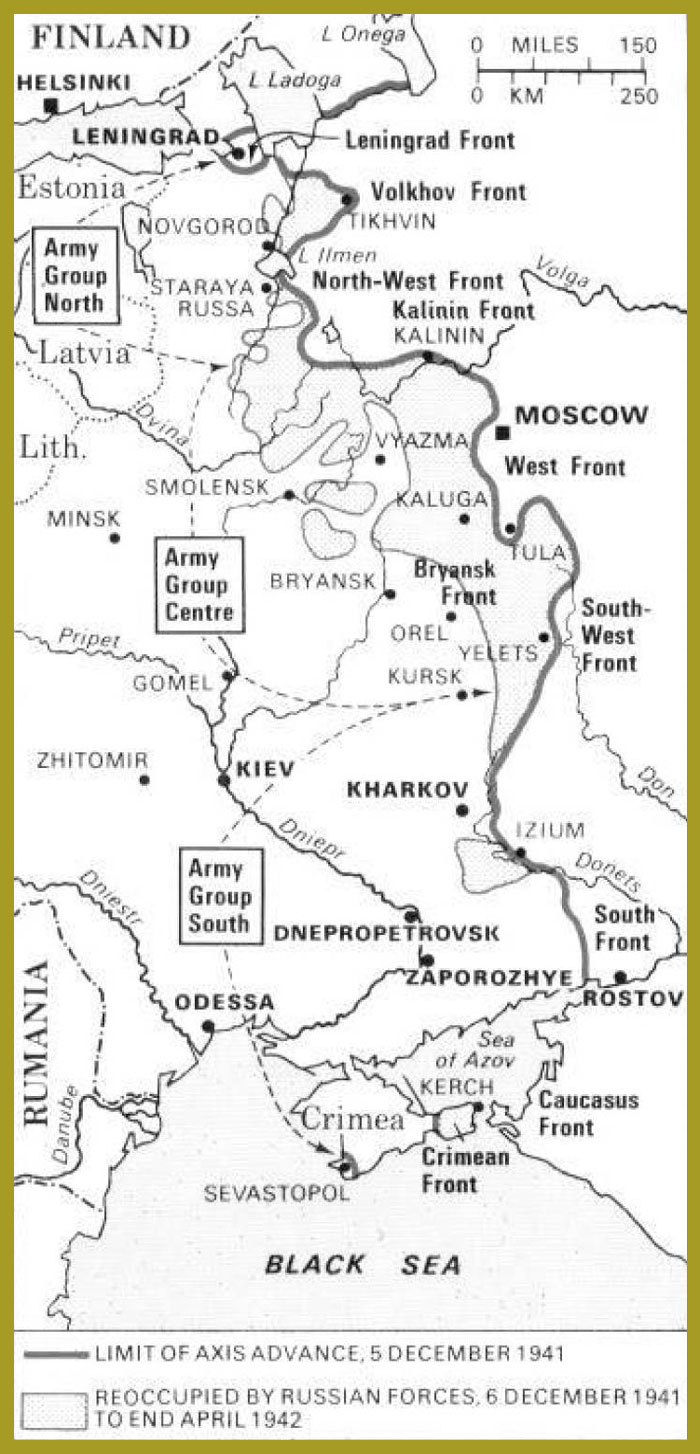

With the recapture of Kalinin and Tula, the Russians removed the immediate threat to Moscow. Their offensive drove on into late February, and German troops took refuge in strongly fortified defensive positions (called hedgehogs) in hope of holding out until fresh troops could arrive. Hitler had ordered 'No retreat,' and airborne supplies kept many enclaves going through the winter. But Operation Barbarossa had foundered in the snowfields of Russia. The Soviets were regaining ground from Leningrad to the Crimea.

During the fall of 1941, the Russians were able to evacuate much of their factory equipment and many key workers to the east, where they began to rebuild their industrial machine. Railroad equipment was also evacuated, giving the Soviets an edge in the number of locomotives and freight cars per mile of track. The transportation breakdown foreseen by Hitler did not materialize, and Russian troop reserves were built up in Siberia to replace the great losses incurred on the Eastern Front. At the same time, war materiel from the West began to reach Russia via Archangel, Murmansk, Vladivostok and Persia.

Since Operation Barbarossa had been designed to achieve a quick victory during the summer months, German troops had never been equipped for winter warfare. Soviet troops by contrast, were routinely equipped with clothing and vehicles appropriate to the theater of operations. The Soviet Supreme Command (Stavka) had rallied from the shock of invasion to make effective use of the huge army that had been so wastefully deployed in June of 1941.

The Russian counteroffensive that began on 5-6 December saw immediate and dramatic gains on many fronts. The siege of Moscow was broken by the Kalinin, West and South-West Fronts (army groups). Supplies began to reach Leningrad in time to avert universal starvation in the besieged city. In the south, the Kerch Isthmus was retaken and the Crimea re-entered with help from the Red Navy. The Russians had gone all the way back to Velikiye Luki and Mozhaisk before they had to rest and regroup in late February 1942.

The Red Army launches its counteroffensive.

Russian territory regained by the end of April 1942.

A political meeting of the Russian Twentieth Army near Smolensk.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com