RICHARD NATKIEL

ATLAS OF WORLD WAR II

The Axis attack on A lam Halfa failed to achieve its objectives.

Rommel's staff confer as the Allied defense turns into counterattack.

Rommel had to hold the new line of defense or be overwhelmed - he lacked both the vehicles and the fuel for a mobile battle. By the same token he could not retreat. On 6 September, Axis forces were back where they had started, committed to an immediate counterattack for every foot of disputed ground.

In his new command, General Montgomery lived up to his reputation as a careful planner who emphasized both training and morale. Eighth Army had suffered many changes of fortune and command in the North African Theater, and morale had eroded to a serious degree. Failures of co-operation and confidence had resulted in faulty operations, and Montgomery addressed himself to rebuilding Eighth Army into an optimum fighting unit. At the same time, he was amassing a force superior to the Germans' in every respect: troops, tanks, guns and aircraft.

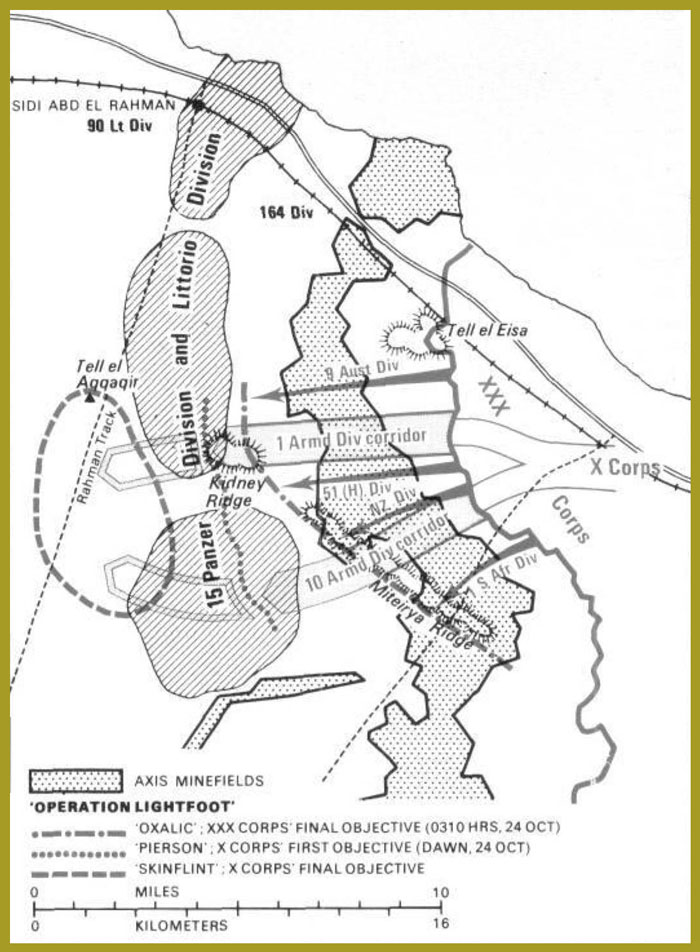

The Germans were well dug in along a line between the sea and the Qattara Depression, and Montgomery's plan was to attack north of the Miteirya Ridge. The infantry of XXX Corps was to push forward to the Oxalic Line and open corridors through the minefields for passage of the X Corps' Sherman tanks, which were finally proving a match for the German Mark IV. Axis forward defenses were manned largely by Italian troops, and Rommel was hospitalized in Germany; he did not arrive until 25 October, when the battle was underway. General Stumme commanded in his absence.

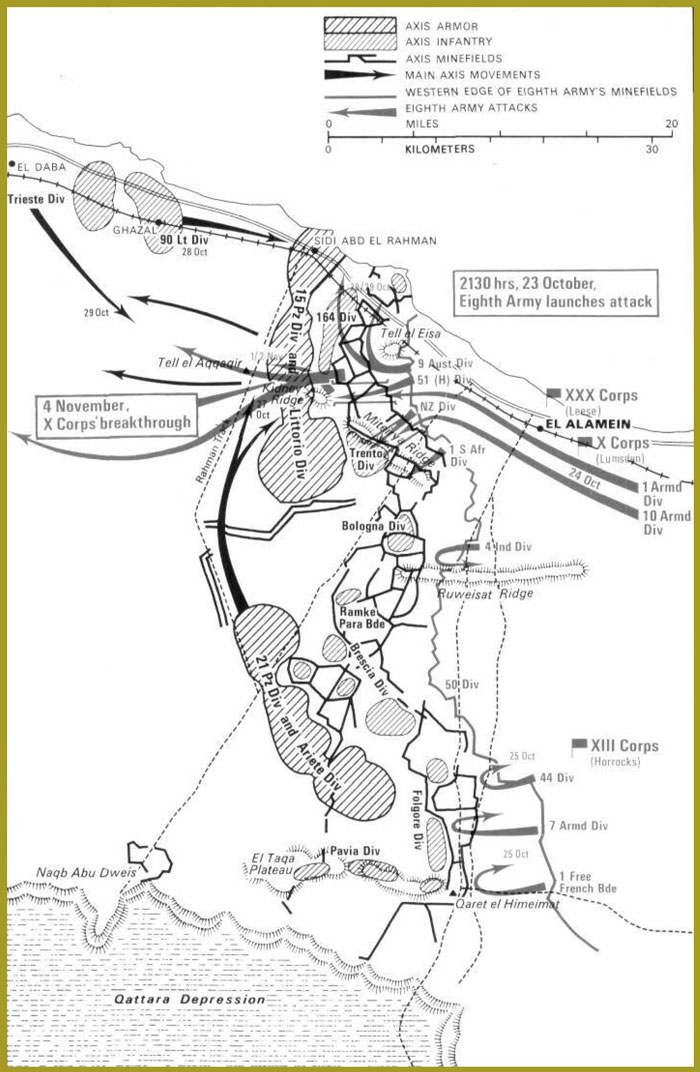

The British infantry made a good start toward its objectives on 24 October, but it proved impossible to move the tanks forward as planned. The German 21st Panzer Division was kept out of the main battle for several days by diversionary efforts from XIII Corps, and the German defense suffered as a result of General Stumme's death from a heart attack during the first day of fighting. The Axis fuel shortage had become critical with the sinking of two tankers in Tobruk Harbor.

When Rommel returned to North Africa, he launched a series of unsuccessful counterattacks that ended on 3 November, when the British armor began to break through into open ground. Hitler at first forbade a withdrawal, but by 4 November Axis losses had made it inevitable. Rommel and his remaining forces made good their retreat.

The attack plan for corridors to be driven through Axis minefields to provide safe passage for Allied tanks.

General Montgomery directs operations at El Alamein. On his right is General Sir Brian Horrocks.

Italian infantrymen in the field at El Alamein.

The second battle saw the Eighth Army repel Axis attacks.

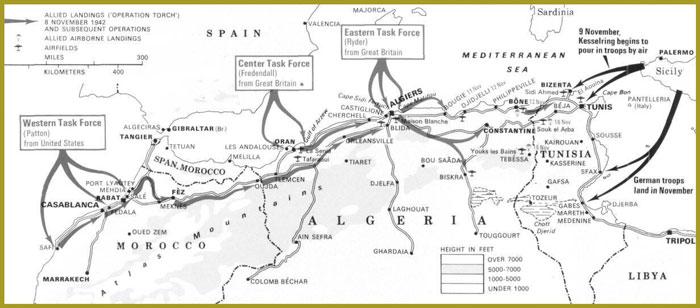

On 8 November 1942, four days after Rommel began to retreat from El Alamein, American and British forces made a series of landings in French North Africa. This operation, code-named Torch, was the first real Allied effort of the war. It was hoped that the numerous Vichy French forces in North Africa would not resist the landings, and the US had undertaken diplomatic missions to local French leaders with this object in view. (Anglo-French relations were still embittered by the events of 1940.) Despite these efforts, sporadic French opposition delayed planned Allied attacks on Casablanca and Mehdia, and two destroyers were lost off Algiers. However, the weakest point of the Allied plan was its failure to occupy Tunisia in the first landings. German troops began to arrive there on 9 November to cover Rommel's retreat and formed a defensive perimeter.

The Allied capture of Vichy leader Admiral Darlan at Algiers helped diminish resistance from French forces; fewer than 2000 casualties were incurred in the three main landing areas. The largest difficulty was pushing the considerable Allied force the 400 miles to Tunis before the Germans could pour in troops and aircraft from Sicily. This they did with great speed, on instructions from Hitler and Commander in Chief Mediterranean Field Marshal Kesselring. Allied forces under General Dwight D Eisenhower, American Commander in Chief of the Torch operation, were stopped short in Tunisia by early December.

US troops march on Algiers Maison Blanche airfield.

The Operation Torch landings.

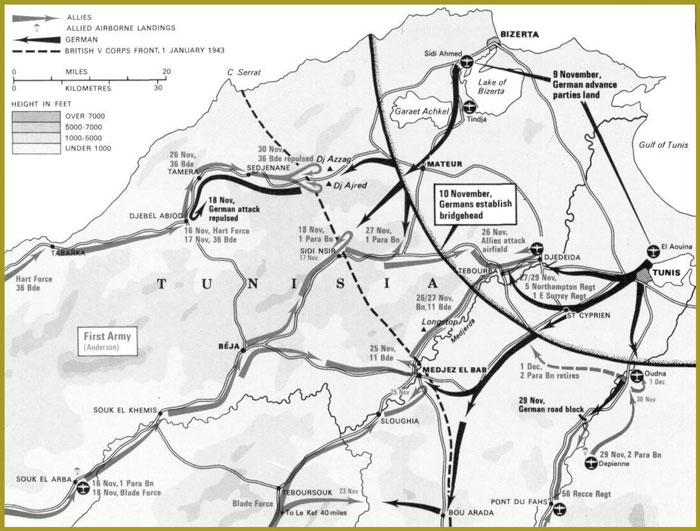

The Allied push into Tunisia.

The Germans reinforce.

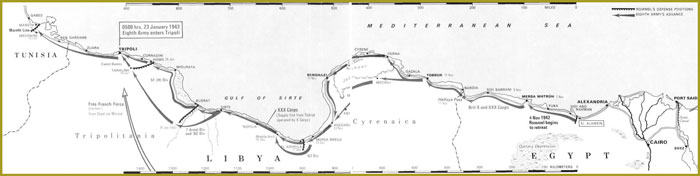

Eighth Army's pursuit of Rommel's forces was hampered by weather and supply problems. It took Montgomery almost three weeks to reach Agedabia (23 November 1942), and he had to halt there until he was resupplied. Soon after, the short-lived German position at El Agheila was outflanked and the race toward Tunisia resumed.

The port of Tripoli offered the British hope of alleviating their supply problems, but the Germans got there first and did as much damage as they could to port installations before pushing on to Tunisia. The British reached Tripoli on 23 January 1943, and it was not until mid- March that the port began to function effectively as a pipeline for British supplies. Meanwhile, Axis forces had consolidated behind the Mareth Line after inflicting 10,000 casualties on Allied troops from the Torch landings at the Battle of Kasserine. Rommel now faced Montgomery's Eighth Army in his last battle in Africa - a bitter fight that raged from 6 to 27 March. Axis forces were outflanked, and by mid-April had retreated up the coast to form a tight perimeter on the hills around Bizerta and Tunis.

Rommel urged evacuation of German and Italian forces from Africa when he returned to Germany, but his counsel was ignored. Thirteen understrength Axis divisions sought to defend Tunisia against 19 Allied divisions that had recovered from their earlier reverses to take on an overwhelming superiority in air power and armor. The Allies had 1200 tanks to the Axis' 130, 1500 guns to the Axis' 500.

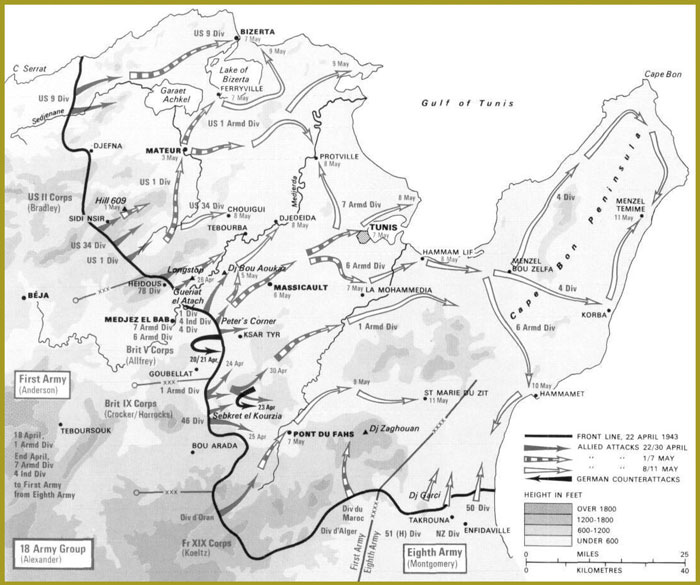

Hill 609 was hotly contested by American forces seeking access to the so-called Mousetrap Valley leading to the coastal plain. British troops made some progress at Longstop Hill and Peter's Corner, which commanded the Medjerda Valley. Then General Alexander switched experienced units from Eighth Army to V Corps, which made possible a decisive victory. Allied troops broke through in early May. Tunis fell on the 7th, ana five days later Italy's Marshal Messe and Germany's General von Arnim surrendered with some quarter of a million troops. These forces would be sorely missed by Hitler when the Allies launched their invasion of Italy.

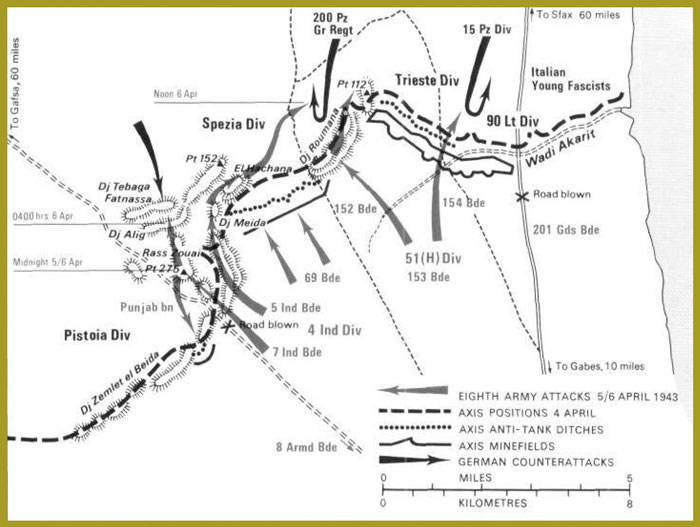

The Eighth Army's attempt to progress up Tunisia's east coast was delayed at Wadi Akarit.

The Allied conquest of Tunisia. Bizerta and Tunis fell on 7 May.

The Eighth Army's progress in the wake of El Alamein.

The Wehrmacht advance with difficulty along a muddy Russian road, 1941.

The Winter War: Finland, 1939-40

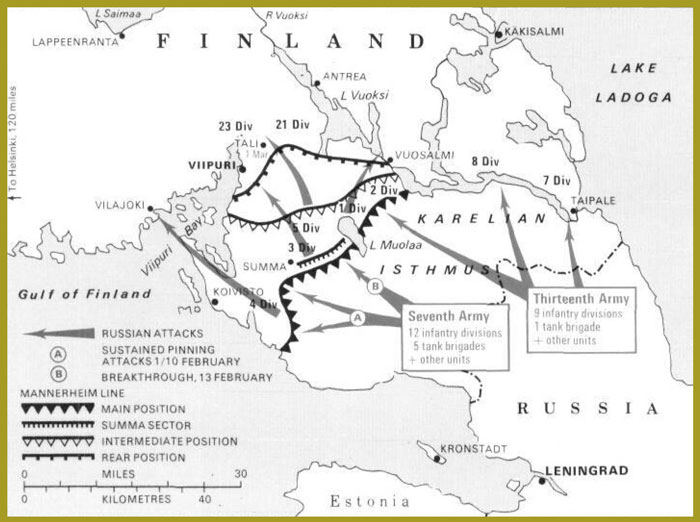

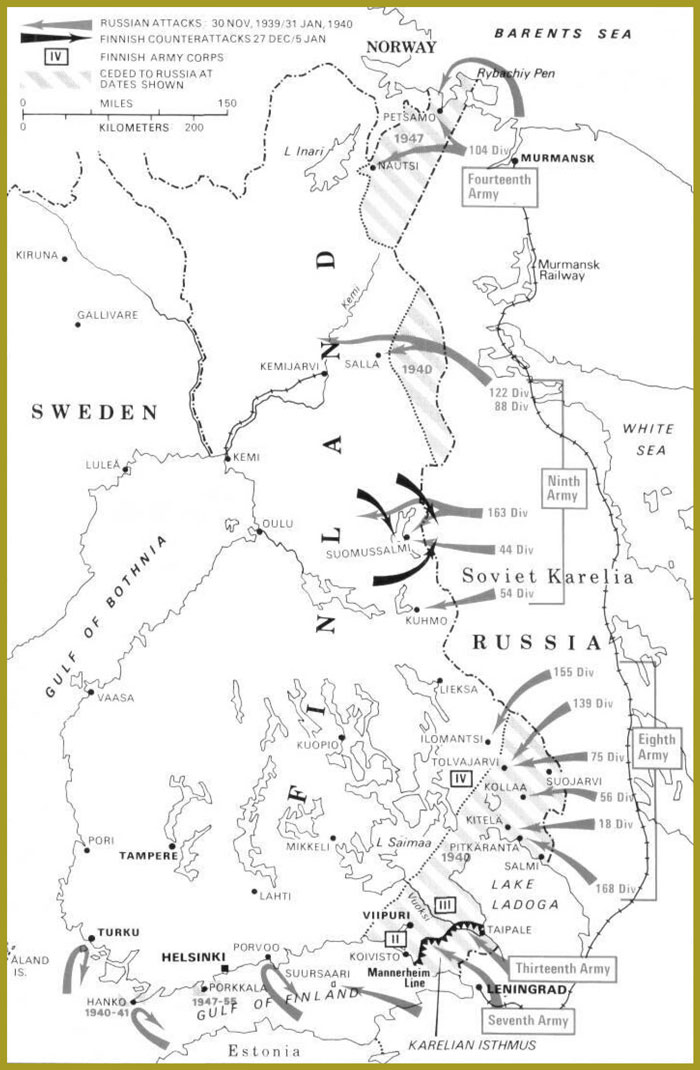

On 30 November 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Finland, after failing to obtain territorial concessions demanded in early October. Five different Soviet armies crossed the Russo-Finnish frontier on four major fronts, but the conquest of this small neighboring nation proved much more difficult than had been foreseen. Deep snow and heavy forest forced Russian tanks and transports to stay on the roads, where they were easy targets for the mobile, well-trained Finnish ski troops. Russian convoys were shot up and separated, and formations were isolated and defeated in detail. The Finns never had more than nine divisions in the field, with few guns and almost no tanks. But their confidence was high, and they had the advantage of fighting on familiar ground with tactics suited to the terrain.

By 31 January 1940, the Russians had made deep penetrations in the north by dint of superior numbers, but the Mannerheim Line, on the Karelian Isthmus, was holding on. The Seventh and Thirteenth Soviet Armies assaulted this line from 1 through 13 February with forces that included six tank brigades and 21 infantry divisions. A massive bombardment preceded these attacks, which achieved a breakthrough in mid- February. The Finns were forced to surrender, and to cede the Karelian Isthmus and considerable territory in the north. They would seek to make good these losses the following year in an alliance with Nazi Germany.

The Finnish fight was solitary and ultimately hopeless, because the British and French Governments feared to arouse Soviet hostility by involving themselves. Nevertheless, the Russo-Finnish War had far-reaching consequences in the international community. As a result of it, the French Government fell due to dissension about helping the Finns, and the League of Nations was thoroughly discredited. Hitler formed a false impression of Soviet inefficiency that probably influenced his decision to turn on his Russian ally. And the Red Army was awakened to deep-seated internal problems that became subject to reform in the months that followed.

The Russians breach Finland's Mannerheim Line in February.

Soviet soldiers dismantle Finnish anti-tank obstacles.

Earlier Soviet penetration in the north and east from November 1939 had met effective Finnish resistance.

Military Balance on the Eastern Front

The German High Command spent almost a year planning the invasion of Russia, code-named Operation Barbarossa. Three different plans were devised, of which the one giving priority to the capture of Leningrad was chosen. German leaders estimated Red Army strength along the frontier at some 155 divisions (in fact, there were 170 within operational distance.) The front was divided in half by the Pripet Marshes. In the north, von Leeb's Army Group North was to aim itself against Leningrad, where it faced an almost equal number of Russian divisions. However, these were deployed so far forward that they were vulnerable to being pushed back against the coast. Von Bock's Army Group Centre, with two Panzer armies, was the strongest German force in the field; facing it was the comparatively weak Red Army West Front. Most Soviet troops were south of the Pripet Marshes, positioned to defend the agricultural and industrial wealth of the Ukraine. Von Rundstedt's Army Group South was to thrust southeast against these forces.

The German plan called for swift penetration deep into Russia in June, to destroy the Red Army long before winter. A massive German buildup began, but Stalin and his advisors were so determined not to give Hitler any excuse to attack that they ignored all the warning signs. In fact, the Red Army was still on a peacetime footing when the invasion began on 22 June. Most units were widely scattered for summer training; others were too close to the western frontier. The reforms that followed upon the Russo-Finnish War were far from complete, and there was almost no Russian reserve to deal with deep incursions. The Germans had good reason to be optimistic about the invasion of Russia.

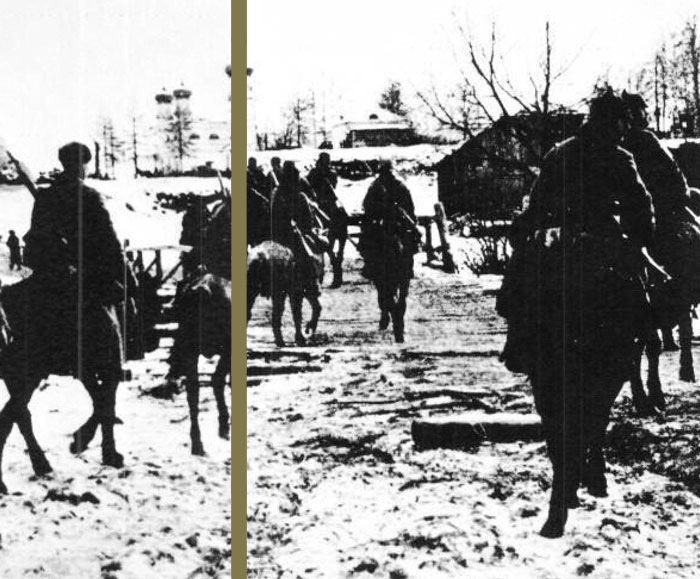

Soviet cavalrymen on the march, 1941. Horse-mounted troops were more mobile than tanks in the severe Russian winter conditions, and were thus more effective than appearances suggested.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com