Text by BRYAN PERRETT, colour plates by PETER SARSON and TONY BRYAN

BRITISH TANKS in N. AFRICA 1940-42

In his Tobruk Field-Marshal Lord Carver analyses the disastrous defeat in the Gazala/ Knightsbridge battles and mentions, inter alia, the indirect influence of Lawrence of Arabia. Regarded in the inter-war years as the fount of all desert wisdom, and specifically endorsed in 1935

Some armour was shipped to the Middle East still in UK livery, with unmodified radios, engines and filters and required tropicalising. Here HMS York looms behind A10s and A13s of 2 RTR, newly landed in October 1940, still in 3rd Armd. Bde. markings with BEF '0046' mobilisation serials. 2 RTR and 3rd Hussars were rushed out to reinforce 7th Armd. Div. for Operation 'Compass' even by Liddell Hart, Lawrence's writings stressed the analogy of desert warfare as resembling sea warfare. Mobility, independence of bases, the ignoring of fixed directions and strategic areas, fluidity, dispersal, mystification of the enemy - these were the themes developed by Lawrence, the supreme 'Irregular'. But the desert armies of the Second World War were organised and trained along strictly Regular lines, and the philosophy of the virtually self-sufficient camel-raid served them ill. The Deutsches Afrika Korps did not practice dispersion, and although it suffered occasionally from the consequent vulnerability to air attack, its concentration all too often made it the stronger contestant at the point of contact. Those British commanders who formed their judgements in the light of historical precedent found Allenby a more rewarding source than Lawrence.

Two further generalisations were that the desert war was 'a tactician's paradise and a quartermaster's hell'. The first is only partly valid. While there were areas of hard, level going, the desert also contained a wide variety of landscapes limiting to the freedom of mechanised forces: treacherous salt marshes, deep wadis, boulder fields, shifting dunes, and the ancient sea cliffs which formed escarpments. Certain areas were of prime importance: El Alamein, where the Qattara Depression and the coast cut the available frontage to 40 miles; Halfaya Pass and Solium, which provided a means of climbing the escarpment from the coastal plain; and the deep-water harbour of Tobruk, possession of which eased the logistic burdens of either side. It was in these areas that the majority of the decisive fighting took place. Particularly significant was the Benghazi Bulge; British possession of its airfields allowed convoys to run through the Mediterranean Narrows to Malta, but the Bulge was easily vulnerable to outflanking via the crosscountry route Agedabia-Msus-Mechili, and was untenable in itself.

As for the desert being a quartermaster's hell, this may well understate the case. The integrity of mechanised armies was totally dependent on a huge consumption of water and fuel. In launching his reluctant invasion of Egypt in 1940 with an essentially marching infantry army, Graziani predicted that a desert defeat would rapidly escalate into a disaster, and so it transpired: beaten at Sidi Barrani, tens of thousands of Italians surrendered rather than endure the horrors of a waterless retreat.

Logistics were of even greater importance in the desert than in other theatres of war. Each side operated from distant bases, and since fuel is a self-consuming load, the further they advanced the less reached them. Victorious armies had their advances terminated as much by supply difficulties as by enemy action; conversely, the closer an army retreated to its source of supply, the more troops it was able to maintain in the field. After Alamein Montgomery could only pursue the enemy with a fraction of the forces that had fought in that battle, and then only by stripping the transport from the formations left behind. After the fall of Tobruk Rommel could advance deep into Egypt only by virtue of captured stores, and captured transport to move them.

Lack of fuel haunted armoured commanders of both sides. The Royal Navy's sinking of a critical Axis supply convoy on the night of 8/9 November 1941 forced Rommel to abandon a major attack on Tobruk and seriously inhibited his conduct of the later stages of the 'Crusader' fighting.

Radio silence was a frequent tactical necessity; here a troop leader resorts to semaphoring the signal 'Advance'. Note sun compass platform on right.

Further naval and air interference left his tanks so short of fuel at Alamein that he strove to avoid a mobile battle which must inevitably lead to the destruction of the DAK. Seeing this, Montgomery embarked on a 'crumbling' offensive, attacking first in one place and then in another, so forcing the Panzers of Rommel's counter-attack force to burn up precious fuel as they moved up and down the front.

The cause of British fuel shortages wras insidious rather than dramatic. In contrast to the robust German 'jerrycans', British fuel was shipped forward in tins that were aptly nicknamed 'flimsies'. Unequal not merely to rough handling but even to the inevitable jostling of supply trucks, they frequently burst at the seams and leaked their contents into the sand. Eventually they were replaced by a direct copy of the jerry can.

The attitudes of the combatants has led to the campaign being described as 'the last of the gentlemen's wars', and at the outset a certain fin de siécle professional courtesy was not unknown. It was initially considered bad form to shoot up a crew escaping from a stricken tank; but before long both sides recognised that trained men were harder to replace than tanks. There were isolated incidents of which neither army had any reason to feel proud; but by and large, once the heat of battle had cooled, each side treated its prisoners very fairly. There was no love lost between them, but rather a mutual respect for men who could stand up to the harsh demands of desert fighting.

For the desert was cruel, and impartial. In the searing heat of noon it was impossible to touch the metal of a tank; in the freezing nights a man might shiver, sleepless, even though he wore every stitch he possessed. There were sandstorms which might last for days. With careful management a man might save enough of his water ration for a cursory wash and shave; nonetheless, after some days in the field it became possible to recognise a companion in the dark by his smell. The desert was far from sterile. Despite strict codes of hygiene, the human waste of large armies inevitably attracted flies in their millions, which swarmed maddeningly around leaguer areas, spreading their filth, until movement or a kham seen brought temporary relief. Most men suffered from desert sores. The inevitable small cuts and grazes were invaded by dirt and flies, and were painful and slow to heal.

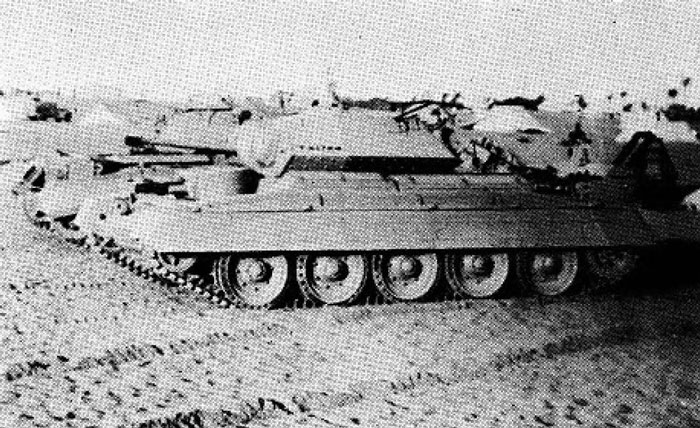

A13 Mk IIs photographed in August 1941. Visible are differing mantlet patterns, a steel helmet used as a headlight cover (right), and a small squadron mark on the turret front (centre) - possibly indicating 2nd Armd. Div., who authorised this practice.

The enforced celibacy was also a trial. In more hospitable climes the British Army, traditionally puritanical, prescribed Cold Showers and Healthy Sport as a panacea for disturbing thoughts. In the desert such remedies were impractical; consequently, formations returning to the Delta or Cairo for rest tended to go hard for the professional ladies of Egypt. The more open-minded Axis armies maintained field bordellos, and one of these establishments actually succeeded in delaying 8th Army's advance on Tripoli. As they stormed along the coast road 40 RTR came across its staff' waiting angrily by the roadside, their transport having been appropriated by their last customers to expedite their own escape. As the regiment paused to comfort these unhappy women, Authority roared up the column to put a stop to the party: the encounter was not, in his opinion, of such importance as to justify a temporary halt in the North African campaign.

In the end it is the shared experience and the comradeship which are remembered. The 8th Army had a personality all its own, and its style and dash were reflected in its vehicles, its dress and even its speech. Those who served in it are justifiably proud of the fact.

Clear study of an A13 of 2 RTR shortly after arrival in Egypt, with straight-edged 'Caunter' camouflage and ED pennants added.

For space reasons, the following notes omit detail of vehicles covered separately in other titles in this series: the M3 Stuart ('Honey'), in Vanguard No. 17, the M3 Lee/Grant in Vanguard No. 6, the Churchill in Vanguard No. 13, and the M4 Sherman in Vanguard No. 15.

During the pre-war years it had been believed that the Royal Armoured Corps1 would require three classes of tank: the Light, for Imperial policing, reconnaissance, and to equip divisional cavalry regiments of infantry divisions; Cruisers, the principal equipment of the armoured divisions; and Infantry tanks, heavily armoured to support infantry assaults on fortified positions. By 1939 all three had been under development for some time, although Infantry tanks were not present in Egypt at the outbreak of war with Italy in 1940.

1Created shortly before the war, the RAC incorporated the cavalry and the RTR. Pre-war, each considered the other a threat to its continued existence; the mutual hostility of 1939 disappeared in the shared experience of battle, though separate traditions were preserved.

Engine 66hp Rolls-Royce, Mks II, III; 88hp Meadows subsequent Marks. Protection 14mm max. Armament 1 × .303 or .50 MG (Mks II-IV), 1 × .303 plus 1 x .50 (V, VI), 1 × 7.92mm plus 1 × 15mm MGs (VIC). Crew Commander/gunner, driver (Mks II-IV); commander, gunner, driver (V, VI). Max. speed 35mph.

Very fast, but so thinly armoured that they were vulnerable to small-calibre AP weapons and even near-misses by HE shells, the Mks II-VI served in the desert. The Light tanks performed their reconnaissance rdle adequately, and were at their best beating up supply convoys; although capable of defeating the wretched Italian CV-33S -little better than tracked MG carriers-they had no other place in the tank battle. It was maliciously hinted by RTR officers that their cavalry colleagues felt at home in the vehicle due to its distinctly equine motion; if driven too fast it suffered 'reversed steering', an unnerving and self-explanatory phenomenon. Decreasing numbers served until late 1941.

Mk I (A9)

Eng. 150hp AEC.Prot. 14mm max. Arm. 1 × 2-pdr., 1 × .303 MG, water-cooled, co-axial; 2 × .303 in subsidiary forward turrets. Crew Commander, loader/operator, gunner, driver, plus two hull gunners if MG turrets manned. Weight 12 tons. Max. speed 25mph.

Originally classed as a Medium to replace the Vickers Medium, the A9 employed the Vickers 'slow motion' suspension. Crew shortages often led to the subsidiary turrets being used only as stowage space. 125 vehicles built. The last Ags to see action fought in Operation 'Crusader'.

Mk II (A10)

Eng. & susp. As A9. Prot. 30mm max. Arm. 1 × 2-pdr., 1 × .303, water-cooled, co-ax.; Mk IIA, co-ax. MG changed to 7.92mm air-cooled Besa, plus second Besa, hull front. Crew C, L/O, G, D; plus hull G in Mk IIA. Wt. 13¾ tons. Max. speed 15mph.

Designed as Infantry tank version of A9, with subsidiary turrets removed and 30mm frontal armour; 175 examples were built, the last being withdrawn from service at the end of 1941. Although classified as a Heavy Cruiser it was too slow for the role, and by 1940 its armour was too thin to allow effective infantry support; the A10 thus fell unhappily between two stools. A few were converted to Close Support tanks by substitution of a 3.7m. howitzer for the 2-pdr.

Mk IV (A13)

Eng. 340hp Nuffield Liberty. Prot. 30mm max. Arm. 1 × 2-pdr., 1 × .303, water-cooled, co-ax.; Mk IVA, co-ax. MG changed to 7.92mm air-cooled Besa. Crew C, L/O, G, D. Wt. 14¾ tons. Max. speed 30mph.

From Mk III onwards British Cruisers adopted the Christie suspension, demonstrated successfully by BT types on Russia's 1936 manoeuvres. The Mk III, apart from the Nuffield Liberty engine and Christie suspension, was very similar to the A10; it did not serve in the desert, but led directly to the A13 which did. The latter had sharply angled and undercut turret sides giving a degree of spaced-armour protection; some 335 were built, the last being withdrawn after Operation

'Crusader' and sent to Cyprus to equip units of 25 Corps' island defence 'Crusader Force'.

Mk V, Covenanter

Eng. 300hp Meadows. Prot, 40mm max. Arm. 1 × 2-pdr., 1 × 7.92mm Besa co-ax. Crew C, L/O, G, D. Wt. 18 tons. Max, speed 31mph.

Over 1,700 were built, but only a handful went to the Middle East, probably limited to training; photos of examples in forward areas may possibly suggest some use in action, if orders of battle included them under the similar 2-pdr. Crusader. The engine cooling system gave problems in this theatre. A logical development of the A13, the Covenanter had a more streamlined turret through better use of angled plate.

Mk VI, Crusader (A15)

Eng. 340hp Nuffield Liberty. Prot. 40mm max. (Mk I), 49mm (Mk II), 51mm (Mk III). Arm. 1 × 2-pdr., 1 × 7.92mm Besa co-ax., 1 × 7.92mm Besa in subsidiary turret (Mk I, part run Mk II); 1 × 6-pdr., 1 × Besa co-ax. (Mk III). Crew C, L/O, G, D, plus hull G if subsidiary turret manned. Wt. 19 tons (Mks I, II), 19¾ tons (Mk III). Max, speed 27mph.

Its five large road wheels and sleekly angled.

Crusader I, T.43744, photographed at an Egyptian base camp. (RAC Tank Museum)

Inside Tobruk, September 1941: an A9 crew of 1 RTR cast off camouflage netting and prepare for action. Forward sub-turrets were often unmanned, due to manpower shortages; and the desperate need for AA weapons in the Tobruk perimeter led to at least one MG being removed from each tank for the purpose.

Wt. 16-17 Max. speed 15mph.

This Vickers Armstrong Ltd. private venture was accepted as a mass-production supplement to the Matilda in 1939; over 8,000 were built, representing 25 per cent of Britain's entire tank production, and after North Africa many were converted to a variety of special roles. It employed the 'slow-motion' suspension which had proved itself on the A9 and A10 ; and was a byword for reliability - by the time 40 RTR reached Tunisia some of its tanks were still going strong after 3,000 - plus operational miles. The two-man turret crew was a disadvantage rectified, by cramped internal re-arrangement, on the Mks III and V. Although armament was as inadequate as in all other British tanks of the period, the diminutive size of the Valentine - height 7ft. 5½ins. - allowed it to obtain a good hulldown position in any convenient fold in the ground. Valentine first saw action with 8 RTR in Operation 'Crusader', and subsequently fought throughout the campaign, a few 6-pdr.-armed models arriving in time for the Tunisian campaign.

Mk IV, Churchill (A22)

Eng. 350hp Bedford. Prot. 102mm max. Arm. 1 × 6-pdr., 1 × 7.92mm Besa co-ax., 1 × Besa in hull front. Crew C, L/O, G, D, hull G. Wt. 39 tons. Max. speed 12½mph.

These figures relate to the Mk III Churchill, of which six fought under direct command of 1st Armoured Div. HQ in an experimental unit, 'Kingforce', at Second Alamein. For details of this and subsequent Tunisian service by this very successful tank, see Vanguard No. 13.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com