J. ARNOLD, S. SINTON, illustrated by DARKO PAVLOVIC

US COMMANDERS OF WORLD WAR II. NAVY AND USMC

Born in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1887, Alexander "Archie" Vandegrift came from a military family. Both of his grandfathers had fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. Failing to gain admission to West Point, he attended the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. He received a commission as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps in 1909. Until 1925, Vandegrift spent most of his service time in the Caribbean region, including duty in Cuba, Nicaragua, and the Panama Canal Zone. He participated in the 1914 Vera Cruz expedition and served three tours in Haiti. He was with the Marine Expeditionary Force in China in 1927-29 and again from 1935 to 1937. Vandegrift applied his considerable experience with amphibious landings when he worked on the Tentative Manual of Landing Operations. This document codified valuable theoretical knowledge that the Marine Corps had acquired about amphibious warfare.

The beginning of World War Two found Vandegrift working as an assistant to the Commandant of the Marine Corps. In this capacity, he labored to reform the corps and make it war ready. Late in 1941, Vandegrift took command of the 1st Marine Division. Admiral Ernest King told Vandegrift that his division need not expect to enter combat before 1943. Thus, it was a major surprise for him to learn that his marines had been chosen to spearhead the first American land-sea counter-offensive in the Pacific: Operation Watch- tower, the invasion of Tulagi and Guadalcanal, islands of which he had never heard. His unready troops had a chance for only one brief rehearsal, which Vandegrift later described as "a complete bust," before they sailed for the Solomon Islands in August 1942. The night before the assault, he wrote to his wife, "Whatever happens you'll know I did my best. Let us hope that best will be enough."

The navy's premature abandonment of the landing force meant that the marines on Guadalcanal lacked ammunition and food as well as radar and radios, construction equipment, and even barbed wire. The iron-willed Vandegrift "uttered no complaint and let no doubt enter his mind that the Corps would hold Guadalcanal, with or without help from the Navy." A long, miserable campaign ensued, during which Vandegrift exhibited sterling leadership. Vandegrift's determination and persistence during the Guadalcanal campaign were key ingredients to eventual victory. If necessary, he planned to melt into the jungle with his men and conduct guerilla warfare rather than give up. Vandegrift won both the Navy Cross and the Congressional Medal of Honor for his conduct on Guadalcanal. After four months of hardship on Guadalcanal, a number of Vandegrift's surviving marines were underweight, dehydrated, malarial, or shell-shocked. Many were so weak that they had to be helped up and over the rails of the ships that evacuated them. Of those who were shell-shocked, Vandegrift later said, "There but for the grace of God go I."

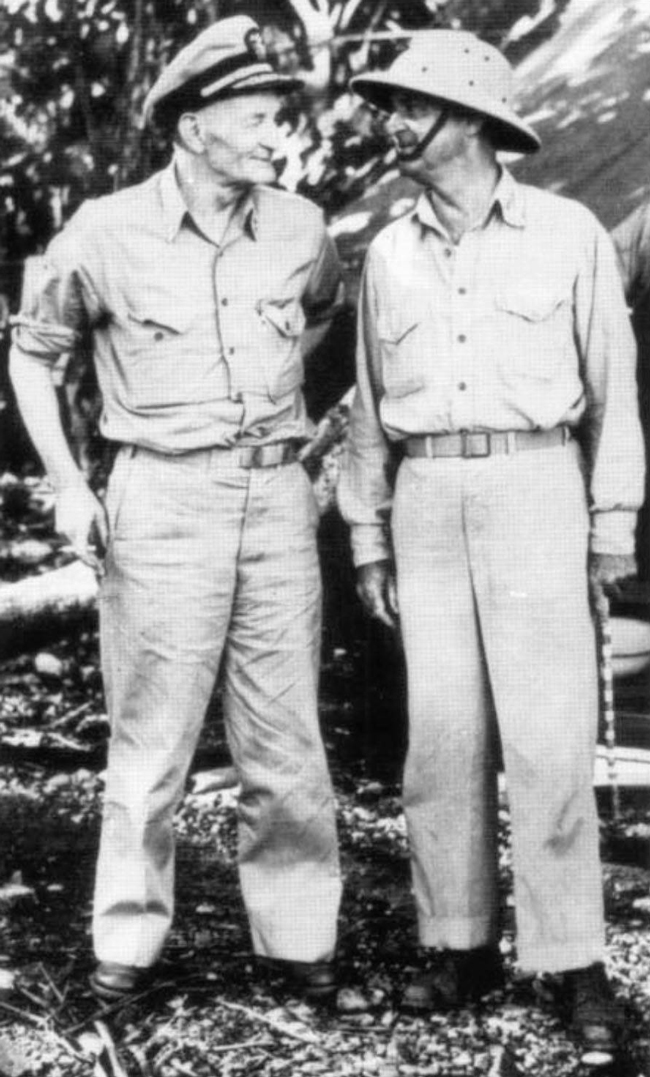

General Alexander Vandegrift (right) confers with Admiral Turner. Command and control struggles with Turner exacerbated the campaign's problems. Turner was Vandegrift's superior and wanted to direct the land campaign. Vandegrift believed that he should have undisputed tactical control. As a result, the marines did not receive much-needed logistical support. Vandegrift appealed up the chain of command until, finally, President Roosevelt personally intervened to order help for the beleaguered marines. (US Naval Historical Center)

Vandegrift (right) is with Admiral John McCain, who helped keep Guadalcanal's "Cactus Airforce" flying. Vandegrift's indefatigable determination to hold Guadalcanal led to victory in this pivotal campaign. A captured Japanese document underscored the importance of the struggle: "It must be said that the success or failure in recapturing Guadalcanal Island, and the vital naval battles related to it, is the fork in the road which leads to victory for them or for us." (National Archives)

Promoted to lieutenant-general in 1943, Vandegrift assumed command of General MacArthur's 1st Marine Amphibious Corps. He directed the landing operations in Bougainville in 1944 until he received appointment as 18th Marine Corps Commandant. In this capacity, he became the first active duty marine to achieve the rank of full general. He had to address serious controversies involving inter-service rivalries. The new commandant wrote from Washington to his friend and successor, Roy Geiger, "Many times have I longed ... for the peaceful calm of a bombing raid on Bougainville."

The uneasy compromise worked out on Guadalcanal, whereby navy commanders exercised undisputed control only during the actual landing, failed to solve numerous problems. Moreover, the bloody amphibious assaults against well-defended Japanese islands such as Iwo Jima, where 21,000 defenders killed 6,000 marines and inflicted 26,000 total casualties, distressed both the American public and its government. Some questioned the competence of the Marine Corps. Vandegrift energetically defended the corps, explaining that Pacific combat against a fanatical, well-fortified enemy inevitably involved heavy cost: "No one realizes more than the Marine Corps that there is no Road Road to Tokyo."

The war's end brought a new challenge to Vandegrift's beloved Marine Corps. As part of a rapid demobilization process, some influential people, including President Harry Truman himself, urged that the corps be merged into a single, unified service. Truman caustically commented that Marine Corps advocates relied upon "the world's second-biggest propaganda machine" in order to exist. Vandegrift skillfully lobbied Congress to retain the corps. His efforts helped lead to a compromise by which the corps remained a separate service within the Navy Department.

General Holland Smith on Saipan in August 1944. Behind his wirerim glasses and craggy, friendly looking features, Smith was an iron-willed marine. He believed that the marines should master the art of "doing the impossible well." (National Archives)

After almost a 40-year-long tour, Vandegrift left active duty in December 1947 and retired in 1949. He died in 1973. His place in American military history is secured by his triumph over great adversity on Guadalcanal.

Born in Seale, Alabama, in 1882, at an early age Holland Smith showed an interest in books about Napoleon and other military leaders. Although he was offered a place at the US Naval Academy, his father demanded that he pursue a law degree instead. Nonetheless, Smith later followed his dreams by enlisting in the marines and receiving a second lieutenant's commission in 1905. During a 1916 expedition to Santo Domingo, he first experienced combat. Here too he began to pay serious attention to the intricacies of amphibious warfare. Smith served with the marines in World War One and won the Croix de Guerre for courage at the Battle of Belleau Wood.

He combined battlefield bravery with brains. He graduated from the Naval War College in 1921. Between the wars, Smith developed new amphibious tactics. He also went against entrenched doctrines by predicting that the next war in the Pacific would depend upon amphibious assaults, rather than decisive clashes between battle fleets. Following a stint at Marine Corps headquarters from 1937 to 1939, Smith received promotion to brigadier-general. In September 1939, Smith assumed command of the 1st Marine Brigade. He began practicing amphibious landings. The experience highlighted the lack of suitable landing craft. Along with boat-builder Andrew Higgins, Smith designed a practical assault boat, its well as an amphibious tractor.

Once war began, Major-General Smith held a stateside assignment directing amphibious training. He wanted a combat command, and in June 1943 persuaded Admiral Nimitz to appoint him to an amphibious command. He served as Head of the Joint Army-Marine 5th Amphibious Corps in the Central Pacific. The horrific assault on Tarawa, in which landing craft ran aground on the coral reef and marines had to wade to shore under heavy fire, angered Smith. He called it a "futile sacrifice of Marines." With characteristic bluntness, he demanded improvements, including more amphibious tractors, better landing craft, and increased naval bombardment.

His prickly personality caused numerous conflicts with fellow officers. It did not help that Smith freely criticized officers who, in his opinion, lacked experience or were too old. He also believed that speed in the attack saved lives and was sharply critical of cautious officers. His criticisms offended many, all of whom agreed with one officer's observation: "General Smith was a sorehead, indignant and griping about everything." He earned the nickname "Howling Mad" Smith.

Smith received his first chance at independent command during the invasion of Saipan. The (altering performance of the army's 27th Division persuaded him to relieve its commander. He knew that this step, a marine general relieving an army general, would cause an inter-service firestorm. Nonetheless, he firmly believed the action necessary, "I know I'm sticking my neck out ... I don't care what they do to me. I'll be 63 years old next April and I'll retire anytime after that." Until this time, five army divisional generals had been relieved of command in the Pacific, so Smith's action had solid precedents. Yet it did cause an enormous controversy. The press also turned against Smith, labeling him a "reckless butcher."

Having distinguished himself in combat in World War One, Holland Smith, shown here bending over to talk with a wounded marine, understood the horrible cost of combat. He labored hard to make their job easier. He later recalled the impact of Tarawa: "I could not forget the sight of Marines floating in the lagoon or lying on the beaches at Tarawa, men who died assaulting defenses which should have been taken out by naval gunfire." (National Archives)

Still, he rose in rank to lieutenant-general and commander of the Pacific Fleet's entire marine force. He commanded the initial assault on Iwo Jima. He had argued for more pre-invasion bombardment. He felt betrayed by the ensuing heavy casualties and requested reassignment in July 1945. For the rest of the war, he supervised training in San Diego. After the war. Smith vigorously continued the war with his pen. He tried to vindicate his own decisions, and the Marine Corps in general, in a series of partisan, controversial articles. As a result, his reputation suffered. Smith died in 1967.

Smith's aggressive leadership and blunt opinions made many enemies. His personality partially obscured his real talents. Admiral Raymond Spruance called the invasion of Tinian "the most brilliantly conceived and executed amphibious operation of the war" and gave Smith full credit. Smith's absence was fully felt during the invasion of Okinawa. Here, the army's slow progress frustrated Spruance. He doubted whether the army's methodical approach really saved lives and commented, "There are times when I get impatient for some of Holland Smith's drive." No single man did more to advance amphibious doctrine. The eulogy at his funeral accurately portrayed Smith as the "father of amphibious warfare."

Born in Middleburg, Florida in 1885, Roy Geiger did not attend the US Naval Academy but instead earned a law degree from Stetson University. He joined the marines and went through Marine Officers' School at Parris Island in 1909. At this time, he met and befriended "Archie" Vandegrift. Geiger served in Nicaragua and the Philippine Islands in 1912-13 and in Peking from 1913 to 1916. He became one of the first marines to qualify as an aviator and commanded Squadron A, 1st Marine Aviation Force in France during World War One. During the interwar years, Geiger graduated from both the Command and General Staff School and the Army War College. He was head of Marine Corps aviation from 1931 to 1935. Holding the rank of brigadier-general, Geiger served as assistant naval attache for air in London from 1941 to 1942. His acquaintance with Admiral Ghormley and aviation experience made him a natural choice to take command of the mixed force of navy and marine aircraft, the "Cactus Airforce," operating from Guadalcanal.

Promoted to the rank of major-general, Geiger assumed command at Guadalcanal in September 1942. The "Cactus Airforce," officially redesignated as the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, supported both ground operations on Guadalcanal and, more decisively, interdicted Japanese naval efforts to reinforce the island. During this period, Geiger had to contend with numerous problems, ranging from a severe shortage of aviation fuel to keeping the airfield operable amidst frequent Japanese attacks. Through it all, he carefully deployed his scarce resources for specific objectives. Working closely with his friend Vandegrift, Geiger performed flawlessly during the late October battle for Henderson Field. In a remarkable ten-day period, October 16-25, his aviators shot down 103 enemy aircraft, sank a Japanese cruiser, and provided close support for the Marine Infantry. Relieved on Guadalcanal on November 7, Geiger returned to the headquarters of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing on Espiritu Santo. Subsequently, this wing supported the advance in the Solomon Islands.

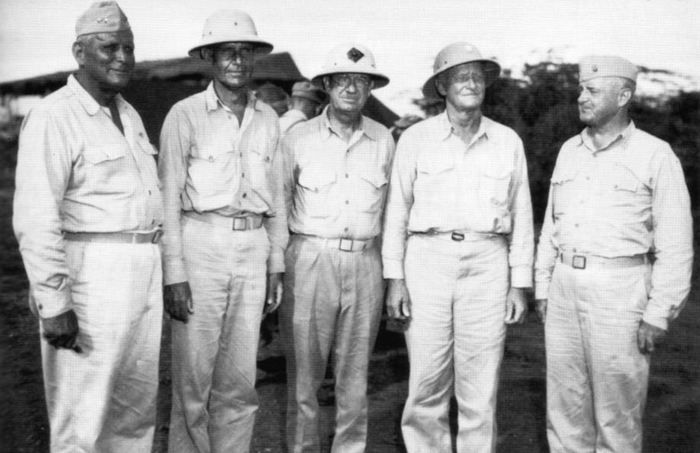

Photographed on Guam in August 1944, from left to right are: General Roy Geiger, Admiral Spruance, General Holland Smith, Admiral Nimitz, and General Vandegrift. Geiger commanded the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing on Guadalcanal. After Japanese battleships savagely bombarded Henderson Field, knocked out half the "Cactus Airforce," and destroyed most fuel supplies, Geiger was told that there was no gas to fill his planes. He replied, "Then by God, find some!" Fuel was even siphoned from disabled aircraft so that a handful of Geiger's planes could fly the ten miles to the target area where Japanese transports unloaded reinforcements. (US Naval Historical Center)

In November 1943, Geiger relieved Vandegrift as the commander of 1st Marine Amphibious Corps, when Vandegrift departed to serve as the Marine Corps Commandant. At this time, the marines were fighting on Bougainville. Geiger subsequently commanded the 1st Marine Amphibious Corps in landings on Guam, Peleliu (by which time it had been redesignated 3d Marine Amphibious Command), and Okinawa. Before the invasion of Guam, Geiger broadcast a speech over loudspeakers on the troop transports: "The eyes of the nation watch you as you go into battle to liberate this former American bastion from the enemy. Make no mistake; it will be a tough, bitter fight against a wily, stubborn foe who will doggedly defend Guam against this invasion. May the glorious tradition of the Marine esprit tie corps spur you to victory. You have been honored." Like all marines, Geiger believed in front-line leadership. At Peleliu, he came ashore to look things over on the first day, before the beachhead was secured. He had to be talked into returning to his ship by anxious subordinates. Promoted to lieutenant- general, Geiger briefly took over command of the 10th Army from General Buckner in 1945, when that army officer was killed on Okinawa. He thus became the first US marine ever to command a field army. Having succeeded Holland Smith as Commanding General Fleet Marine Force Pacific, Geiger was the only marine general present at the Japanese surrender ceremony on board the battleship Missouri. Geiger continued as Fleet Marine Commander until 1946. He died the next year while still on active duty.

A big bear of a man, Geiger is best remembered for his valuable service during the Guadalcanal campaign.

Born in 1885 in Elkton, Maryland, Julian Smith did not attend the Naval Academy but, rather, received his undergraduate degree from the University of Delaware. He joined the Marine Corps and received a commission in 1909. After service in the Panama Canal Zone, he participated in the action at Vera Cruz in 1914 and at Santo Domingo the following year. He was an instructor at Marine Corps Schools from 1918-19 and, thereafter, commanded a machine gun battalion in Cuba. He performed various staff and training duties between the wars, including director of operations and training division at the Marine Corps headquarters from 1935 to 1938. He continued in training assignments through May 1943. Holding the rank of major- general, he then assumed command of the 2d Marine Division.

Smith led the division in the assault on Betio, the two-mile-long island that commanded the Tarawa Atoll. The navy promised to "obliterate the defenses on Betio." Believing the navy was being too optimistic, Smith reminded planners, "Gentlemen, remember one thing. When the Marines meet the enemy at bayonet point, the only armor a Marine will have will be his khaki shirt." The day before the assault, he sent a message to the troops: "What we do here will set the standard for all future operations in the Central Pacific Area ... Our people back home are eagerly awaiting news of victories ... your success will add new laurels to the glorious traditions of our Corps. Good luck, and God bless you all."

General Julian Smith is shown aboard the Maryland during the Tarawa landing. Smith's 2d Marine Division had a three-day fight to capture Betio. When a senior general inspected the island's 291 acres of ruined fortifications, he said with shock, "I don't see how they ever took Tarawa. It's the most completely defended island I ever saw." Looking at the survivors, the general added, "I passed boys who had lived yesterday a thousand times and looked older than their fathers. Dirty, unshaven, with gaunt almost sightless eyes, they had survived the ordeal, but it had chilled their souls. They found it hard to believe they were actually alive." (US Naval Historical Center)

Confronted by an incredible array of defenses, including British 8-inch artillery captured at Singapore as well as defenders determined to, in the words of their leader, "withstand assault by a million men for a hundred years," the assault foundered. By noon of the first day, November 20, 1943, the marine loss rate had climbed over 20 percent. Reports from the beach said, "Issue in doubt." Smoke obscured Smith's view of the assault from the deck of the Maryland. Smith and Admiral Turner held an emergency staff meeting. In the uncertainty over whether the requested reinforcements would arrive, Smith planned to lead ashore an emergency force composed of his headquarters personnel. In the event, this proved unnecessary when a late afternoon report came from the commander ashore, "Casualties many. Percentage dead not known. Combat efficiency: we are winning!" According to official records, the three-day campaign to capture Betio's 291 acres was "the bitterest fighting in the history of the Marine Corps." The loss of 1,300 Americans killed shocked everyone.

Smith went from divisional commander to command the expeditionary forces of the 3d Fleet from April to December 1944, and then returned to his training duties as commander of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island from 1944 to 1946. He was a lieutenant-general upon his retirement at the end of 1946 and died in 1975.

Mild mannered but determined and decisive, Julian Smith will forever be associated with the terrible battle at Tarawa.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com