J. ARNOLD, S. SINTON, illustrated by DARKO PAVLOVIC

US COMMANDERS OF WORLD WAR II. NAVY AND USMC

Born in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1888, Theodore Wilkinson did not have to travel far to attend the US Naval Academy. He graduated first in his class from Annapolis in 1909 and received a commission two years later. Wilkinson won the Congressional Medal of Honor for leading a landing party during the 1914 invasion of Vera Cruz. During World War One, Wilkinson served as a naval attache in Paris and then aboard American ships in European waters. Prior to World War Two, he commanded destroyers, performed staff work, and commanded the battleship Mississippi. Wilkinson became Director of Naval Intelligence in October 1941 and, thus, became partially involved in the post-Pearl Harbor investigation of intelligence failures. Exonerated, in August 1942 Wilkinson assumed command of a battleship division in the Pacific but saw no action. Next came a brief tour as Deputy to Vice Admiral Halsey.

In July 1943, Wilkinson assumed the role that became the crowning achievement of his professional life: commander of the 3d Amphibious Force. In this capacity, he supervised amphibious landings during both the American drive though the Solomon Islands and General MacArthur's advance in New Guinea. Amphibious planning and implementation were particularly complex operations. Wilkinson met the challenge ably. The 3d Amphibious Force conducted the landings during the Central Pacific campaign. Thereafter, Wilkinson received promotion to rice admiral in August 1944. The following January, he flew to Pearl Harbor to begin planning for the projected invasion of the Japanese mainland. In the event, he instead supervised the landing of American occupation troops in September 1945. Wilkinson received a post-war assignment to the strategic bombing survey of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in January 1946. He drowned the next month, when his car drove off a pier in Norfolk, Virginia.

Wilkinson began his career in a blaze of glory at Vera Cruz. His wartime service required meticulous planning, an essential duty for the American amphibious advance to prosper, but was without the credit attached to fighting sailors aboard carriers, cruisers, and submarines. He died a premature, tragic death.

Born in Hampton, Iowa in 1875, William Leahy graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1897. For the next twenty years, his active duty assignments included service in the Spanish American War, the Philippine revolt, the Boxer Rebellion, the occupation of Nicaragua, the Haiti campaign, and the 1916 expedition against Pancho Villa. In summary, he crammed as much active duty into this period as possible. While commanding the Secretary of the Navy's dispatch boat, Dolphin, in 1916, Leahy met the young Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin Roosevelt. During the course of several cruises, the two became friends. The next year, Leahy commanded the battleship Nevada. In 1927, Rear Admiral Leahy received promotion to the important job of Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance. He next commanded the destroyers assigned to the fleet's Scouting Force. From 1933 to 1935 he was Chief of the Bureau of Navigation. Promoted to vice admiral in 1935, he became commander of battleships. Promoted again the next year to full admiral, he commanded the entire Battle Force. His friendship with Roosevelt led to Leahy's appointment, in 1937, as Chief of Naval Operations.

Leahy was certain that war with Japan would come, so he began preparing strategic plans for coalition warfare that later became the foundation of American global strategy. He participated in secret prewar meetings with the British as part of his coalition-building efforts. Leahy reached retirement age in 1939. Rather than lose his services, Roosevelt appointed him Governor of Puerto Rico. The outbreak of war in Europe prompted the president to recall Leahy and, subsequently, send him to Vichy France as ambassador. Leahy accomplished little in this capacity but his unswerving devotion to Roosevelt's policies impressed the president. Roosevelt recalled Leahy to Washington, in April 1942, to join his inner circle of advisers and return to active duty.

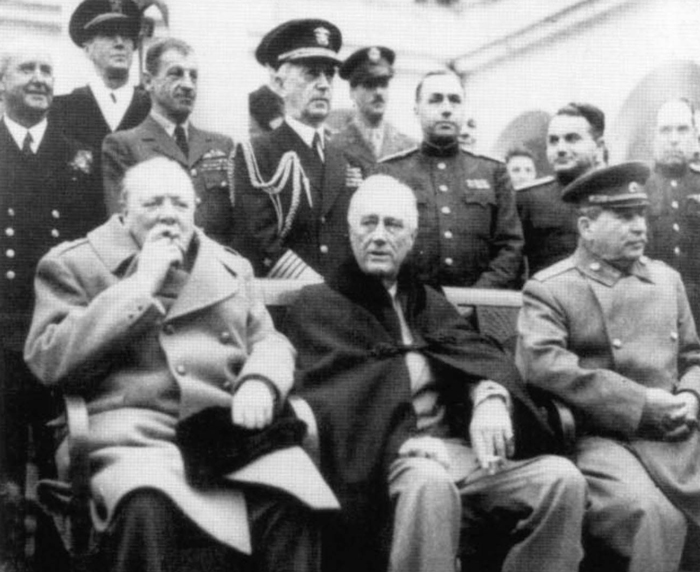

At the Yalta Conference, Admiral William D. Leahy stands behind President Roosevelt, as befitting his position as one of the powers behind the throne. Leahy mastered political-military affairs to a high degree, winning the trust of most of the top-ranking leaders he dealt with. (National Archives)

Leahy spent the remainder of the war working to solve the novel challenges of total war on a world scale. In 1942, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) was a new organization, combining the senior heads of each service. The JCS's task was to advise Roosevelt on military strategy and to implement his decisions. General George Marshall suggested that Leahy be appointed to a special post to provide liaison between the JCS and Roosevelt. Marshall's inspired choice recognized that Leahy was senior in service to the chiefs and was liked and respected by them. Moreover, Roosevelt trusted him. Therefore, he would be an ideal channel between the president and the military. Also, as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Leahy restored a balance to the JCS of two admirals and two generals. In July 1942, Leahy became the first chief of staff to the commander-in-chief.

Leahy now held a powerful position, greatly enhanced by his close relationship with Roosevelt. He met with Roosevelt daily, vetted which military men saw the president and which military issues received the president's attention, and attended most of the major wartime conferences with the various Allies. He was a central figure at the highest level of the military chain of command. Because he invariably sided with Roosevelt, the JCS members came to think of him as "one of them" as opposed to "one of us." Still, they retained their admiration for Leahy. Leahy, in turn, supported the "Germany first" strategy, while also sharing in the desire to put more effort into the Pacific War. This was typical of his altitude of compromise in order to get divergent interests acting in harmony. Leahy opposed the invasion of Japan at the war's end because he believed it would be very costly and that the blockade and strategic bombing would compel Japan's surrender. Leahy labeled the Japanese as barbaric "savages" but was one of very few senior leaders among the high command to oppose the use of the atomic bomb, partially on moral grounds.

Roosevelt successfully urged Congress to create a new rank of five-star admiral and then promoted Leahy to this post. President Truman retained Leahy as chief of staff until 1949, but the two never enjoyed the same warm relationship that characterized Leahy's service to Roosevelt. Leahy died in 1959.

Although Leahy never served at sea or even in the navy during World War Two, his position as senior military adviser to the president made him one of the most, if not the most, influential American military men in the entire war. He seldom contributed original insights into wartime strategy but, rather, harmonized civil-military relations at the highest level so that the war could be effectively pursued.

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania in 1880, Harold Stark graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1903. He served as an aide to Admiral Sims during World War One and an aide to the Secretary of the Navy from 1930 to 1933. Promoted to rear admiral in 1934, Stark was Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance from 1934 to 1937. He rose steadily from commander of a cruiser division to commander of all the cruisers in the Battle Force, and became a vice admiral in 1938, and full admiral in August 1939. At that time, President Roosevelt chose Stark, over more than 50 senior flag officers, for duty as Chief of Naval Operations.

Admiral Harold Stark (center) is shown during an invasion of France inspection tour. To his right is Admiral Kirk and to his left, Admiral John Hall, the commander of the naval forces assigned to Omaha Beach. Stark was the Commander US Naval Forces Europe. Known as London's "oldest American resident," Stark actively participated in all planning for the invasion of France, from early 1942 on. (National Archives)

In November 1940, Stark wrote a memo to President Roosevelt that became one of the most important documents of World War Two. Stark identified four strategic alternatives for the United States: a) to concentrate mainly on hemispheric defense; b) to prepare for an all-out offensive in the Pacific while remaining on the defensive in the Atlantic; c) to make an equal effort in both areas; d) to prepare for a strong offensive in the Atlantic while remaining on the defensive in the Pacific. Stark strongly preferred d, or "dog," in the military alphabet. Stark noted that Great Britain was making a desperate, lonely effort to defeat Germany and that the United States was already strongly supporting the British. Furthermore, Germany was a more deadly military threat to the United States, being both stronger and nearer. His advocacy led to the adoption of "Plan Dog." It was a sharp reversal of the navy's traditional preoccupation with Japan, as described in Plan Orange. Stark's memo led to secret formal talks between American and British service chiefs in January 1941. The chiefs quickly agreed that Germany and Italy must be defeated first. As Chief of Naval Operations, Stark was instrumental in preparing for the expansion of the US Navy into a force capable of fighting in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, a "two-ocean" navy.

Like many naval officers, Stark anticipated that Japanese expansion in the Pacific would lead to war. He did not anticipate the strike against Pearl Harbor. His late November 1941 "war warning" to Pacific commanders proved inadequate in alerting leaders in Hawaii and the Philippines. It later became a source of enormous controversy, with Stark receiving much blame for not sharing intelligence with Admiral Kimmel at Pearl Harbor. Within days after Pearl Harbor, to forestall public and congressional criticism, Roosevelt authorized a major change in the navy's senior leadership. He named Admiral Ernest King Commander-in-Chief of the US Fleet. This decision effectively removed Stark from authority. In March 1942, Stark transferred to London as Commander, US Naval Forces Europe. He held this position until 1945. Stark's duties in London were administrative, rather than operational. His most notable work involved planning for the invasion of France. Stark exhibited good diplomatic skill and was well regarded by the British.

Both the navy and Congress held investigations into Pearl Harbor, compelling Stark to testify' at various times between 1944 and 1946. The initial naval investigation criticized Stark for failing to issue a clear warning. The subsequent congressional investigation was more lenient. In the end, Admiral King changed his negative assessment of Stark's performance. The Secretary of the Navy supported King, and so Stark received formal exoneration. Stark retired in 1946 and died in 1972.

Well-liked and kind, Stark contributed importantly to the key strategic decision to defeat Germany first. His subsequent work in London as a sailor-diplomat also received praise. However, his colossal failure to adequately warn American leaders about the Japanese threat has been roundly criticized by many modern historians. The words of an American lieutenant, who served in the Philippine Air Force, are worth remembering: "Our generals and leaders committed one of the greatest errors possible to military men - that of letting themselves be taken by surprise."

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1888, Alan Kirk graduated from Annapolis in 1909 and received his commission two years later. During World War One, Kirk held a rear area assignment at the Naval Proving Grounds in Dahlgren, Virginia. He served as a naval aide to the president in 1920-21. Kirk graduated from the Naval War College in 1929 and staved on as an instructor until 1931. He was a naval attache in London from 1939 to 1941 and then returned to the United States to become director of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) in March 1941. Captain Kirk tried to make the ONI responsible for both collecting and interpreting intelligence. The Head of the Navy's War Plans, Admiral Richmond Turner, opposed Kirk's notion and succeeded in keeping naval intelligence from becoming centralized. Some historians who specialize in intelligence argue that if Kirk s consolidation had taken place, the navy would have been able to interpret properly the signs of the pending Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. In the event, Kirk escaped blame for Pearl Harbor.

Admiral Alan Kirk watches the D-Day invasion force. (National Archives)

Kirk's first combat assignment of World War Two was as commander of a division of destroyer escorts in the Atlantic Fleet from October 1941 to March 1942. Promoted to rear admiral, he returned to London in March 1942 to serve again as naval attache. Kirk also served as chief of staff to Admiral Stark, the commander of US Naval Forces in Europe. In February 1943, Kirk again assumed an active command when he took charge of the Atlantic Fleet's amphibious forces. He was involved in the planning for Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, and supervised the training of the naval forces that landed American forces on the easternmost beaches of Sicily. Although his task force suffered heavy landing craft losses because of high surf and rock outcroppings, there were very few personnel losses.

Admiral Kirk and General Bradley arrived in the transport area off the American invasion beaches on June 7, 1944. Thereafter, Kirk conducted Eisenhower on a visit to the Normandy beaches. When the minelayer carrying the senior command ran aground off the British beaches, Kirk told Eisenhower that he would make a "kind" report of the incident and, hopefully, the minelayer's commander would escape with a mere reprimand from the Admiralty. Kirk added, "most good officers have a reprimand or two on their records." (National Archives)

Kirk's combination of diplomatic experience in London with his knowledge of amphibious warfare made him the natural choice as commander of US naval forces for the Normandy invasion. He transferred to the United Kingdom in mid-November 1943 and became involved in the planning for Operation Overlord. At this time, many senior British officers, as well as Admiral Stark, believed that Germany would soon collapse and, thus, there would be no need to invade France. This attitude made it difficult to plan seriously to accomplish Kirk's mission as commander of the Western Naval Task Force. Kirk was responsible for bringing American forces across the Channel, providing gunfire support for the assault landing, and defending the assault area from any German naval thrusts. Kirk handled this complex mission well. However, he made the fateful decision to launch the landing craft far out to sea, in many cases 11 miles from the beach. Kirk feared German coastal guns, thought to be in place at Pointe du Hoc. Intelligence officers regarded them as the "most dangerous battery in France.'' In fact, they turned out to be dummies. Meanwhile, the long trip to the beaches sickened soldiers and disrupted landing plans.

Admiral Kirk is aboard a torpedo boat off the Normandy coast in 1944. Ten years after D-Day, Kirk reflected upon the US Navy's contribution and said, "Our greatest asset was the resourcefulness of the American sailor." (National Archives)

Naval gunfire support was enormously useful during operations within the Normandy beachhead. Ten days after the invasion, a German military journal wrote, "The fire curtain provided by the guns of the Navy so far proved to be one of the best trump cards of the Anglo-United States invasion Armies." The US 1st Army relied so heavily upon naval gunfire that Kirk had to warn General Bradley not to become overly dependent on the navy because the naval guns were being worn out by their frequent fire missions and many ships would have to depart soon to support the invasion of southern France. The Western Naval Task Force was dissolved on July 10, 1944. During the Normandy campaign, besides commanding fire support operations, Kirk also supervised the landing of supplies via the artificial harbors. This also proved a difficult technical challenge. In October 1944, Kirk was elevated to command of all US naval forces in France. In this capacity, he supervised the naval forces involved in major river crossings, including most prominently the Rhine crossings in March 1945.

Promoted to vice admiral in May 1945, Kirk served on the navy's General Board until he retired the following March. Thereafter, he held a variety of important diplomatic posts, including Ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1949 to 1951 and Ambassador to the Republic of China (Nationalist China) from 1962 to 1963. Kirk died in 1963.

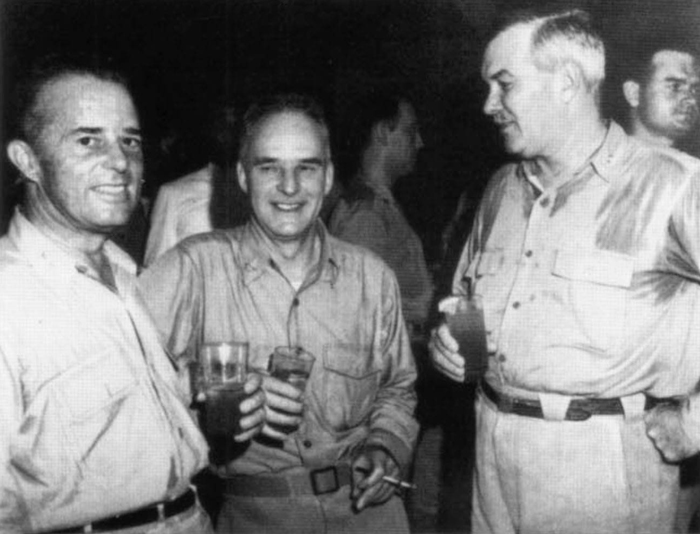

Three cruiser commanders relax between missions. From left to right: Aaron Stanton Merrill, Robert Ward Hayler, and Walden Lee Ainsworth. "Tip" Merrill and "Pug" Ainsworth were particularly prominent as task force commanders during the drive up the Solomon Islands, while Hayler commanded the Honolulu in Ainsworth's task force and conned her through the Battle of Tassafaronga without a scratch. (US Naval Historical Center)

No naval officer serving in the Atlantic was going to shine as much as those admirals serving in the Pacific. Kirk undramatically did his duty with a high level of efficiency. Eisenhower respected his professional ability.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com