MARK R. HENRY, MIKE CHAPPELL

THE US ARMY IN WORLD WAR II. THE PACIFIC

Several service or campaign medals were awarded to Army personnel in World War II. These were given as both the (nil medals (rarely worn) and as ribbon bars. Small metallic devices (appurtenances) were attached to the ribbons to show further service. Army ribbon bars were l⅜in long and ⅜in high, and were worn in rows three or four wide. The mounting bars were originally pinback but by mid-war the modern style pin and clutch began to be used. Ribbon displays sewn on a cloth backing were also used by senior officers. Ribbons were authorised to be worn above the left pocket of service dress coats and sometimes of shirts, but not on combat or fatigue clothing. Gallantry awards were worn first (top), to be followed by (from the wearer's right to left) good conduct awards, campaign medals, and finally foreign awards.

The American Defense Medal was given to soldiers on active service between September 1939 and 7 December 1941; (his medal distinguished the old regulars and National Guardsmen from the new draftees. A 'foreign service' slide was worn on the medal ribbon by soldiers serving overseas (including Hawaii and Alaska) between those dates; a small (3/16in) bronze star on the ribbon bar represented this slide. This medal was authorised in late 1941.

The American Campaign Medal was awarded for one year's service in the Army between 7 December 1941 and 2 March 1946. Any combat service also qualified a CI to receive this medal. It was authorised in November 1942, and almost every soldier out of training would have received it.

The Asiatic-Pacific Medal ('A&P Medal') was authorised for service in that theatre between December 1941 and March 1946, and has precedence over the ETO Medal. A bronze star device was used to represent awards for participation in campaigns in theatre; a single silver star represented five campaign stars. There are 22 campaign stars possible in this theatre. An arrowhead device was used to mark participation in any amphibious or airborne operation; no more than one arrowhead was authorised for wear by any individual, but this rule was not always obeyed. The A&P Medal was authorised in late 1942.

The European-African-Middle Eastern Medal ('ETO Medal') was authorised for service in theatre between December 1941 and 8 November 1945; it was first issued in November 1942. Campaign stars and the invasion arrowhead were authorised as per the A&P Medal, and 16 campaign stars were possible for service in this theatre.

The Good Conduct Medal (GCM) was awarded to enlisted men who had completed a three-year enlistment with a clean record and superior efficiency. Only service after August 1940 counted. After Pearl Harbor the initial time period was reduced to one year. A tiny metal device shaped as a knot marked each additional award. Officers were not awarded the GCM, as they were always expected to display good conduct, though officers promoted from the enlisted ranks might wear it.

The Purple Heart Medal was awarded for wounds and some injuries received in action. (Frost-bitten feet qualified; trench foot did not.) Additional awards were represented by the use of oakleaf clusters on the ribbon.

The WAC Medal was awarded to Women's Army Auxiliary Corps members who agreed to enlist into the new WAC in 1943. Women joining the WAC after September 1943 were not eligible

The World War II Victory Medal was authorised for all members of the Army who had served between 7 December 1941 and VJ-Day, 2 September 1945.

The previous fatigue uniform of the Army was blue denim pants, shirt and Daisy Mae' - a floppy-brimmed hat nicknamed after a character in the popular hillbilly cartoon strip L'il Abner. In 1938 this was changed to medium weight sage green cotton cloth, woven in a herringbone twill (HBT) pattern. The blue denim remained the fatigue issue until 1941, however. The green of the original HBTs was found to fade quickly in use to an unsuitably light shade. In the Pacific this problem was sometimes remedied by vat-dyeing them en masse to a darker, even blackish colour. In 1943 the HBT manufacture colour was changed to the darker green OD#7 shade.

Most GIs felt that the HBTs were a bit hot and rather slow to dry, but generally pretty good. In North Africa and Europe HBTs were commonly worn as combat clothing alone or over brown woollen uniform for extra protection, camouflage and warmth. One 32nd Division Pacific veteran summed up the question of uniforms with the pithy and convincing comment, 'I don't believe there is any clothing or equipment adequate for jungle fighting'.

The HBT shirts all featured flapped breast pockets and exposed blackened steel '13 star' (or sometimes plain plastic) buttons. The M1942, the first of four patterns, had a two-button waistband with buttoning cuffs and rear 'take-up straps' (tightening tabs); the pleated breast pockets had clip-cornered flaps. The more common M1943 HBT shirt had larger breast pockets, but lost the buttoning cuffs and two-button waistband; it was made in a darker green than the first pattern. The first version of the M1943 shirt had unpleated pockets, while the next had a pinched sort of pleat. The rarely seen last pattern HBT shirt (M1945?) was made with smaller pockets with clipped bottom corners and squared flaps. At the end of the war a new thinner cotton poplin fatigue was just beginning to be issued.

New Guinea, 1942: a battalion commander from the 32nd Division with his staff. They all wear the first pattern HBTs with two-button waistband and pleated pockets (except the visiting Marine officer, who wears USMC pattern utilities with the classic breast pocket stencil). Some of the Army HBTs appear to have been dyed a darker black/green in Australia. The lieutenant-colonel carries a M1928 Thompson SMG.

Rank was rarely displayed on fatigues, though NCO stripes were sometimes inked onto HBT sleeves. According to Capt Edmund G.Love, a 27th Division historian, this formation at one time had coded unit and rank symbols stencilled on the rear of the HBT combat uniform in black - a system copied from the US Marines. The division was identified by an outline parallelogram, enclosing unit symbols - e.g. a T, a 'bar sinister' and an Irish harp shape for the 105th, 106th and 165th Infantry Regiments respectively. Left of this, numbers indicated some ranks (e.g. 8 for sergeant, 15 for captain, etc), and right of it company letters were stencilled. Given the actual conditions of combat, and the frequency with which HBTs had to be replaced, it is doubtful if this complex system was maintained for long. Even in the six Marine divisions, which in 1943-45 seem to have had a thoroughly worked out system of back stencils, it is comparatively rare to see them in combat photographs.

Both HBTs and issue wool shirts commonly featured an extra length of material inside the buttoned closure, intended to be folded across to protect the skin against chemical agents; this 'gas flap' was sometimes cut out by the user. Trouser flys were also made with an extra interior flap of material for the same reason. (In the Normandy landings of 1944 chemically impregnated HBTs and woollens were worn by landing troops as a precaution against chemical warfare.)

The first pattern HBT trousers had sideseam and two rear pockets of a very civilian style. The second pattern (M1943) had thigh cargo pockets and sideseam pockets but no rear ones. The last pattern of the M1943 trousers had pleated thigh cargo pockets.

An HBT one-piece ('jumpsuit') work uniform had been designed in 1938 based on the B1 Air Corps mechanics' coveralls. In 1941, the M1938 was produced in HBT and featured a full buttoning front, an integral bell and a bi-swing/gusseted back; it had two each breast, rear and sideseam pockets. It was intended to be worn loose over other clothing, and the sideseam pockets opened to allow the wearer to reach inside. It was commonly worn by tank crewmen and mechanics but sometimes by other front line troops. It could be cumbersome to take off, and proved uncomfortably hot. A 1943 version was simplified and made in the darker OD colour.

In the field, women initially had to wear men's HBTs and woollens as little else was available. In 1943 one- and two-piece WAC HBT cotton fatigues became available. Both suits had angled flap front thigh patch pockets and used drab plastic buttons. The HBT shirt had two flapped patch pockets. Floppy 'Daisy Mae' hats were worn with HBTs, the special WAAC issue having a slightly longer brim at front than back.

Rendova Island, New Georgia, 1943: GIs wearing M1942 one-piece camouflage uniforms unload a Landing Craft Infantry (LCI). LCIs could carry 200 men; these shallow draft ships would drop anchor, then run aground on the beach, and after dropping their load they winched themselves off by the anchor chain.

The first pattern (HBT) camouflage suits were issued in the South-West Pacific in 1943. This M1942 'frogskin' one-piece zippered suit had a green and brown coloured spot pattern on a pale neutral ground; the outside had a slight green cast to the pattern, and the lining camouflage a light brown cast. Despite this it was not truly reversible, having permanently sewn-in internal suspenders (though many CIs removed these) and pockets only on the outside surface. The suit had pairs of expanding breast and thigh pockets with two-snap flaps, and a gusseted back; the sleeves had a buttoned tab closure. The one-piece M1942 suit was too hot, and its design caused the users problems when responding to an urgent call of nature. The camouflage pattern was effective, but proved to stand out too much when the wearer moved. Some suits were later cut down into shirts worn with HBT pants.

By 1944 an improved two-piece HBT shirt and trouser suit was issued in the same camouflage pattern. It had the same pocket arrangement as the one-piece, although the buttons were concealed. This outfit - which was distinctly different in a number of details from equivalent garments produced for the US Marine Corps - proved more popular than the one-piece suit. Reconnaissance troops and snipers were heavy users of these 'frogskins', but green HBTs were still the most common GI combat clothing in the Pacific. (Camouflage uniforms were experimentally issued to some troops in Normandy in 1944, but were quickly withdrawn due to their dangerous superficial similarity to German Waffen-SS camouflage clothing.)

The 1940 'Daisy Mae' floppy hat was produced first in khaki, then in HBT green for field and motorpool use, and was sometimes worn into combat in the Pacific. In 1941 a short-billed HBT fatigue cap (M1941) was produced, reminiscent of a railroad engineer's cap. The 11th Airborne Division had its own modified khaki version of the M1941 (the 'swing hat') made with a longer bill. These two caps proved popular, and a longer-billed version was produced in 1944.

Philippines, 1944: a team of 1st Cavalry Division long range scouts wear the one-piece 'frogskin' suit, and have painted their soft OD fatigue caps with camouflage colours. All are armed with M1 carbines, the rear centre man with a paratrooper's folding stock version.

The short M1941 (PDQ-20) or 'Parsons' jacket was designed in 1940 by Gen Parsons, and went into production later that year. (The term 'M1 941' is widely used by today's collectors, but was not the contemporary designation; this was simply the 'Jacket, Field, Olive Drab'.) It featured a greenish khaki exterior and a flannel/wool lining, with a buttoned front fly over a zip fastener, an integral rear half-belt, buttoning tabs at the wrists and hips, and two diagonal front 'handwarmer' pockets with buttoned flaps. After several rapid modifications mass production began in 1941 and continued until late 1943. The full production version of the jacket had gussets behind the shoulders, and added epaulettes; the front pocket flaps of the first version were eliminated. It was manufactured in 12 sizes of windproof cotton 'Byrd' cloth or cotton poplin. This jacket was intended for light combat wear, and would be supplemented by the woollen overcoat or the raincoat in seriously bad weather. A thigh-length M1941 arctic or officer's coat similar to a mackinaw was also produced in limited numbers. A women's version of the Parsons jacket was made thigh length with reversed buttoning.

1944: both floppy hats and billed fatigue caps are worn here, with HBT cargo-pocket trousers, by a 4.2in mortar crew; the tube commander (right) still wears the one-piece HBT with 'bi-swing' back. The 4.2in (106mm) mortar excelled at putting down smoke/white phosphorus or HE; it became available in 1943, and units were normally corps-level assets assigned as needed.

Infantrymen were too heavily burdened to carry overcoats and raincoats as a matter of course, so had to rely on the Parsons field jacket for most of their needs; and it quickly garnered a significant body of complaint. It was too short and lightly constructed to stand up to the weather. It showed dirt, and quickly took on a grubby appearance. The jacket's exterior faded to a light khaki drab that could stand out too visibly; on occasion GIs actually wore the jacket inside out to lessen its signature. Soldiers also sometimes removed the collar as too ill-fitting for comfort.

Despite the later issue of the improved M1943 combat jacket, the M1941 stayed in use throughout the war. In Europe, though never particularly popular, its continued wear became a trademark of an old soldier. Ii remained the most common jacket to be seen in the CBI and northern Pacific until VJ-Day.

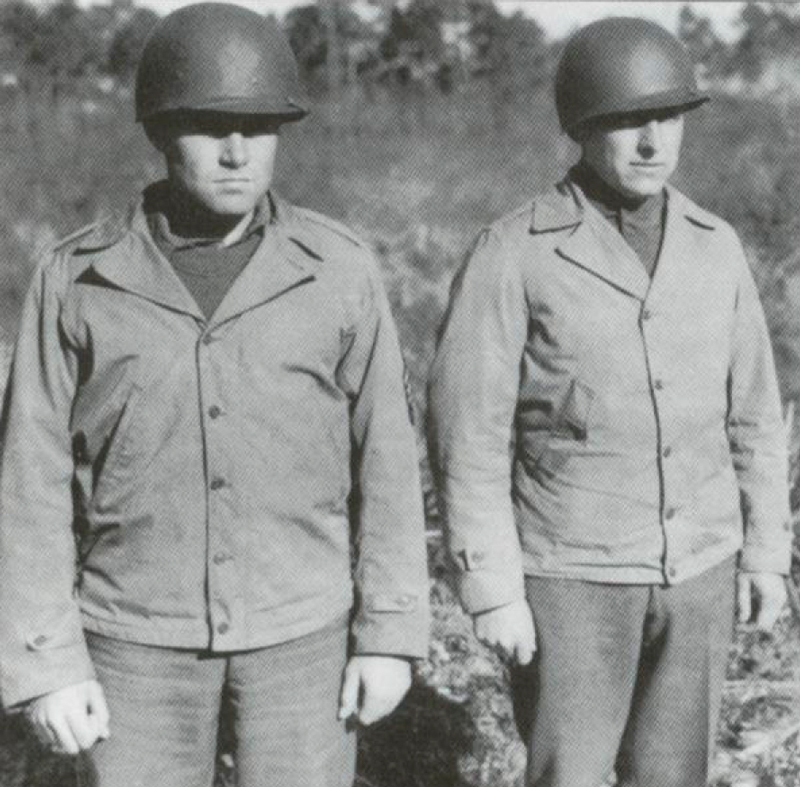

Florida, January 1943: these two sweater-wearing GIs are undergoing amphibious training. At right is the original Parsons jacket with pocket flaps, at left the more common flapless version. Both men wear M1 helmet liners without the steel shell, as was common in garrison and training.

Initially, soldiers used the manganese steel US M1917A1 'dishpan' style helmet, with a rough sand surface and non-reflective OD finish. By mid-1942 large numbers of the M1 steel 'pot' were available. This helmet was to remain in US service until the mid-1980s. The chinstrap attachment brackets were fixed (welded) on the sides of the M1 helmet shell until 1945, when hinged brackets were introduced. Both helmets used a khaki canvas chinstrap with a claw-and-ball fastener.

The unusual feature of the M1 was its light fibre helmet liner which nested inside the steel shell and contained the webbing and leather suspension. The first model liner was thick-edged and made of compressed fibre covered with fabric; a thinner bonded cloth and plastic liner soon replaced this. Both types had a narrow brown leather chinstrap, normally worn up over the front brim of the steel shell. Liners were sometimes worn as separate headgear by GIs away from the front lines.

Okinawa, 1945: lightly equipped GIs of the 96th 'Deadeye' Division look for a place to deploy their Browning M1919 air-cooled machine gun. All wear cargo-pocket HBT trousers and buckle boots. The two-month fight on this island would cost the 10th Army about 7,500 killed and 32,000 wounded.

Some units in the Pacific and Mediterranean painted their helmets in camouflage patterns of large green and brown blotches or smudges. By 1943 helmet netting for the attachment of foliage was available; but as the Japanese used helmet nets, Pacific theatre GIs usually did not. Burlap covers were sometimes fashioned; and in the Pacific, US Marine Corps camouflage covers were also used occasionally. A cumbersome anti-mosquito helmet netting (face veil) cover was later issued. Helmet markings of rank and unit symbols were somewhat common in Europe, but almost unknown in the Pacific. The usual way of wearing a helmet in all theatres was without a net and with the canvas chinstrap pushed up over the rear brim, or left dangling.

The GIs found the M1 steel pot to be a versatile piece of gear; one Army nurse declared that it had 21 uses. Besides headgear, it was most commonly used as a washbasin, entrenching tool, or seat.

Another headgear used by the Army from 1941 was the sunhelmet. This was to be seen early in the war, and was made of a khaki-covered molded fibre; it had numerous grommet airholes and a narrow leather chinstrap. It was later reissued in a slightly darker greenish khaki. The sunhelmet was unpopular and rarely seen in use in the field.

The red/brown 'russet' leather ankle boot (actually termed the 'service shoe') was used by the Army for both garrison and field use in 1941. Called by collectors 'type 1', it was made 'smooth side out' with a toecap and a leather sole. The 'type 2' model of the US ankle boot appeared in late 1941 and featured a composite rubber/leather sole. The 'type 3' boot of 1943 was a 'rough side out' version with an all-rubber sole. In mid-1943 a simplified 'reversed upper' ankle boot was issued; this was 'rough side out' and had no toecap. The 'type 3' and 'reversed upper' boots were for field use only and were heavily treated or dubbined for weatherproofing.

The M1943 or 'buckle boot' began to be seen in both the Pacific and ETC) in late 1944 and rapidly became a favourite. It was made of rough-out leather, and its 16in (40.6cm) height, incorporating an ankle piece closed by straps and two dull steel buckles, obviated the need for leggings. It replaced both the ankle boot/leggings combination and the paratrooper boot as the standard Army-wide footwear.

The Army issued OD green socks of cotton and synthetic mix. These were usually made with extra material woven into the sole area for extra cushioning. Such socks are still issue in the current US Army. Off-white woollen winter or civilian socks were also used.

Light green/khaki M1938 canvas leggings were issued to be worn over the issue ankle boot, to keep out the dust, mud and bugs. Once they were in, the leggings kept them in - and also prevented water from draining away after wading. The standard pattern made of #6 duck canvas used nine brass hooks on the side for lacing, while later versions had eight hooks; each hook had two facing eyelets, so getting the leggings on or off was a time-consuming chore. In both the Pacific and Mediterranean theatres leggings were sometimes cut short or simply dispensed with. In hot weather trousers were commonly worn hanging unbloused over the leggings or boots.

On board ship en route for New Guinea, late 1942: GIs of the 32nd Division armed with a mix of Garands and Springfields - the latter probably for rifle grenadiers only. Note locally-made cloth helmet covers, and first pattern HBTs with buttoned cuffs. Their kit is stowed in general purpose barracks bags.

In the Pacific, the coral sand and rocks and the sodden jungle floor abraded or rotted the soles off boots in a matter of weeks if not days No real solution was found for this problem, though Australian-produced hobnailed GI boots provided better traction. (Hobnailed GI boots were also made in England in small numbers, and used in the ETO.)

Standardised in August 1942, a specially designed jungle boot began to be issued in the South-West Pacific late that year. It was essentially a canvas tennis shoe with the ankle extended to a height of 11 ins (28cm) The sole, welt and toe were rubber, moulded directly to a green canvas upper and leg. Above the ankle the laces passed through hooks instead of grommets, for speed; and there was a full-length sewn-in bellows-type tongue behind the lacing. The jungle boot was light, dried quickly, and was good for quiet work; unfortunately it lacked support for the foot and , ankle. 1 he high top chafed the leg, and was often cut short. The jungle boots were only a limited success; but after the standard shoe they did not go unappreciated - one admiring Merrill's Marauder described the feel of them as like 'walking barefoot over the bosoms of maidens'. By 1945 a leather and canvas jungle boot not unlike the modern US pattern was developed, but it was too late to see wartime service.

Officers might wear any number of boots for field use, from the issue low- quarter to paratrooper boots. Special three-buckle, high- topped cavalry buckle boots I were sometimes worn by senior officers.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com