MARK R. HENRY, MIKE CHAPPELL

THE US ARMY IN WORLD WAR II. THE PACIFIC

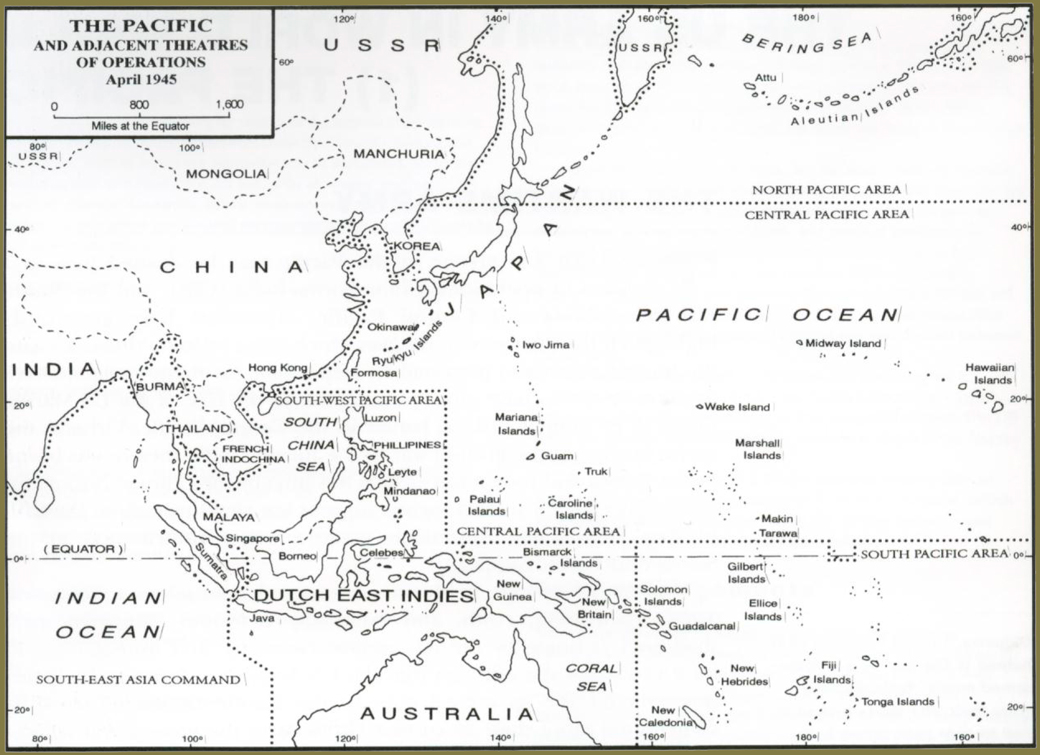

The Allied war effort in the Pacific may be divided into four theatres of operations: China-Burma-India (CBI), and the South, South-West and Central Pacific. Historians have generously highlighted the inter-service rivalries which these separate theatres - and the leading command personalities responsible for them - engendered. Books and movies have given prominence to the role of the US Marine Corps in its dramatic island battles in the Central Pacific. Virtually the entire burden of the ground war in the Burma/India theatre was borne by the British and Indian forces, and in China by the Chinese Nationalist army, although US air and logistic support was vital throughout the CBI. In New Guinea the Australians made a major contribution to the South-West Pacific campaign.

Okinawa, 1945: a wounded GI is helped to the rear by a carbine-armed medic. Typically, they wear their HBT shirts tucked in and trouser cuffs loose; both types of the large-pocket HBT shirts are worn here. The medic's special pouches are pushed back to hang behind his hips on their yoke suspenders; his M4 bayonet is carried on a Japanese leather belt.

The British troops in Burma considered themselves a 'forgotten army', their long, costly, and eventually victorious campaign overshadowed at home by the war against Germany; and over-arching all local rivalries is the odd fact that the US Army, too, seems to be barely remembered for its critical role in the Pacific theatre. The Army contributed more than 20 combat divisions to the ground war against Japan - three times the strength of the US Marine Corps; and it was the Army which stood the first shock of the enemy after Pearl Harbor.

* * *

The active strength of the US Army in 1939 was 174,000, making it a third-rate power. With war on the horizon, a peacetime draft - conscription, which filled local quotas by ballot - was instituted in 1940. It was renewed by Congress in 1941 by a margin of just one vote. The Army was dramatically enlarged, and by July 1941 it stood at more than 1,300,000, with 29 divisions and growing. By 1940 the Army was strong enough to hold its first corps-level manoeuvers since World War I. (A corps was a grouping of two to five divisions, and an army was a grouping of two to five corps.)

Army enlistment was filled by both volunteers and draftees. The rapidly expanding National Guard (Reservists) units were called to the colours and provided some 270,000 men to the Army. The draft included men from the ages of 21 to 35; the lower limit was later dropped to 18 years, but the average age of soldiers was 26, compared to 23 in the US Navy. High peacetime physical standards were steadily eroded to increase the intake, although about one-third of the draftees examined were rejected. Men were inducted for three-year terms, or the duration of hostilities plus six months.

African-Americans were accepted as both volunteers and draftees; they were formed into all-black units mostly officered by whites. A small number of combat units were formed, but generally blacks were posted to support units. Because of ETO manpower shortages in late 1944 they were slowly integrated into white combat units as replacements. The 92nd and 93rd Divisions were all black, and by 1944 10% of the Army's manpower was black.

Beginning in 1942, women were accepted as volunteers in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). In 1943 the WAAC was formally incorporated into the Army as the Women's Army Corps (WAC). By the end of the war about 100,000 WACs would be serving in the Army, including some 6,000 in the South-West Pacific and 10,000 in the European theatre.

New inductees were prodded, inoculated, and given intelligence tests to help the Army place them. The majority of the high test scorers were snapped up by the Air Corps or one of the technical support branches; some of these men were allowed to attend college and were to be inducted at a later date after acquiring important skills (the ASTP programme). Uncle Sam provided new recruits with a full 'government issue' (GI) of clothing, equipment and other necessities; and once caught up in the giant military machine they began to think of themselves as 'GIs', too. Basic training was cut to eight weeks after Pearl Harbor but later rose to a standard 17 weeks. These new men were used to fill out existing Regular, National Guard or new draftee divisions.

The senior officers of the Army were products of the new staff schools at Ft Benning and Leavenworth, and many were veterans of the Great War. Colleges (universities) provided a large cadre of junior officers to start with, but the Army would require many more leaders. With the US Military Academy at West Point tardy in speeding up their four-year curriculum, Army Chief of Staff Gen George C.Marshal founded Officer Candidate Schools (OCS). These OCSs went on to successfully provide 65% of the officers required by the US Army. Promising enlisted men with four to six months' service could be recommended. At first they received 90 days of training in their branch and as leaders, and they soon acquired the nickname '90 day wonders'. The courses were later expanded to about 120 days, but the name stuck. Officers were also created by direct commissioning of civilians with special skills such as doctors, lawyers and engineers.

Ambitious Army planners envisioned that the US would need 200 divisions to achieve victory in Europe and the Pacific. In order to approach this goal it was found necessary to constantly comb men out of existing divisions to create cadres for new units; for instance, the 1st Division lost 80% of its strength in 18 months to these periodic drafts, and the 69th Division lost over 150% of its strength in the 16 months prior to its commitment to combat. This policy severely damaged the ability of existing divisions to train and build a team.

By 1945 8,300,000 men had been enrolled in the Army and Army Air Corps, with a stabilised combat strength of about 91 divisions.

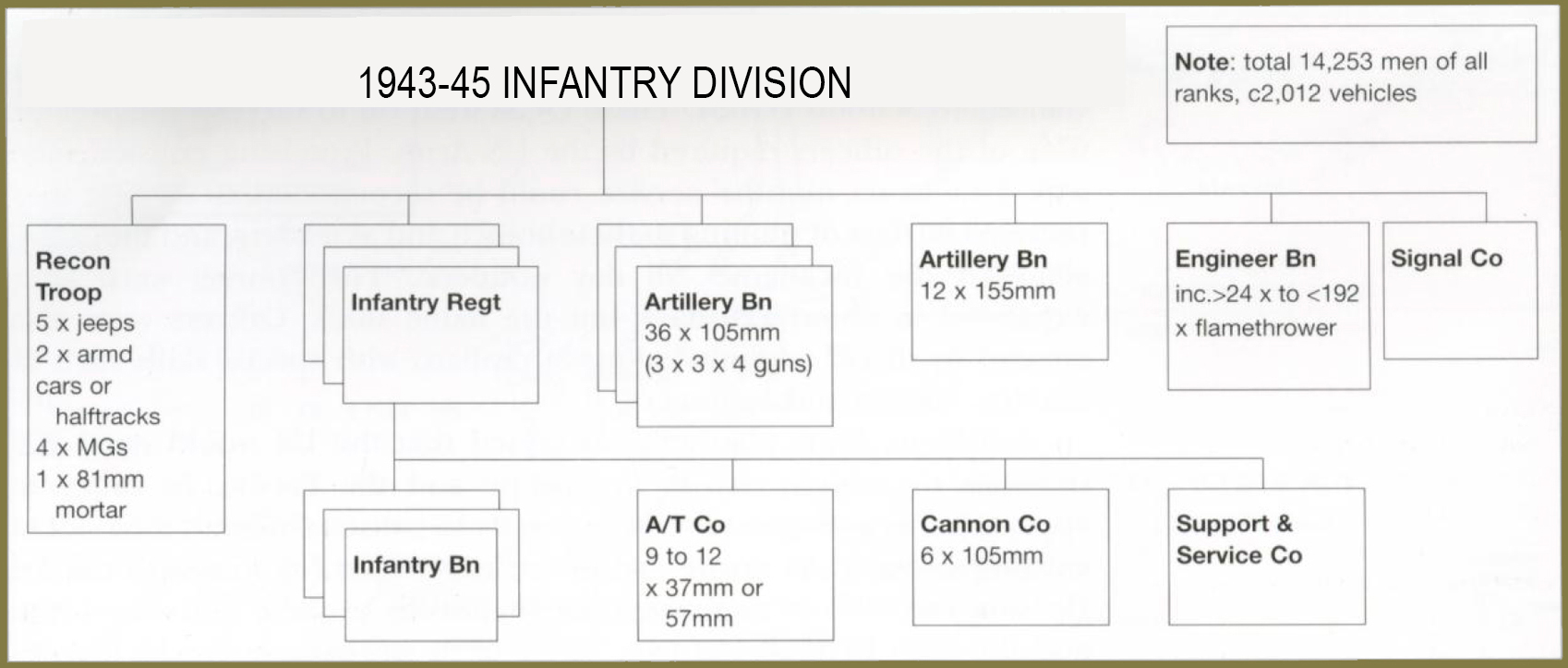

In the late 1930s the Army began to reorganise its divisions. The old musclebound 24,000-man 'square' division built around four infantry regiments was slimmed down to a 15,500-man 'triangular' division with three. With its new organisation and weapons the triangular division essentially retained its firepower but increased its flexibility and mobility. By 1943 the infantry division was further slimmed to 14,253 men, still organised around three infantry regiments.

1942: Gunners strip to the waist to serve their 105mm howitzer. They wear HBT trousers without cargo pockets, and the man in the left foreground wears the first pattern HBT shirt with 'take-up straps' on the waistband. All wear the khaki first pattern floppy hat or 'Daisy Mae'.

In the Pacific the Army employed standard infantry divisions almost exclusively. Exceptions included the US/Filipino 'Philippine Division' of 10,000 men which was destroyed on Corregidor in 1942; and the 13,000-strong 'Hawaiian Division' of 1941-42, which was disbanded to provide cadres for the formation of the 24th and 25th Divisions.

The 11th Airborne (8,200 men) and the specially configured 1st Cavalry Division also served in the Pacific. The Army's horse cavalry consisted of two divisions in 1941. The 1st Cavalry Division (basically two rifle regiments and eventually four artillery battalions, totalling with support units about 12,700 men) was dismounted and served as infantry in New Guinea and the Philippines. The 2nd Cavalry Division was dismounted and converted into a black infantry formation, but was disbanded in 1943. The crack US/Philippines 26th Cavalry Regiment (Philippines Scouts) was destroyed in the fight for Bataan - the starving garrison ate their horses.

An important tactical innovation was the Regimental Combat Team (RCT). These were task forces temporarily extracted from divisions, or independent units under corps control. Some RCTs and other independent units were combined on New Caledonia in 1942 to form the 23rd 'America!' (America/Caledonia) Division. Most common among army/corps level independent combat units were mechanised cavalry groups and squadrons, and artillery, anti-aircraft, tank and tank destroyer battalions. These were attached to divisions or corps as required. Particularly in Europe, these attachments were common and almost permanent. If these combat units had been assembled into formations the US would have fielded approximately 15 additional divisions.

An infantry regiment (4,000 men) had a headquarters company, three infantry battalions, an anti-tank company (9 to 12 x 37mm or 57mm guns), a cannon company (6 x 105mm guns) and a support and services company. In the Pacific the regimental cannon company sometimes had light 75mm or 105mm pack howitzers. Battalions were commanded by majors or lieutenant-colonels and regiments by full colonels. The divisional artillery ('divarty') consisted of one 155mm battalion (12 guns) and three 105mm (36 guns). Regimental cannon companies were often absorbed into the divisional artillery. Later in the war self-propelled 105mm guns (M7 Priests) were substituted for the 105mm towed guns.

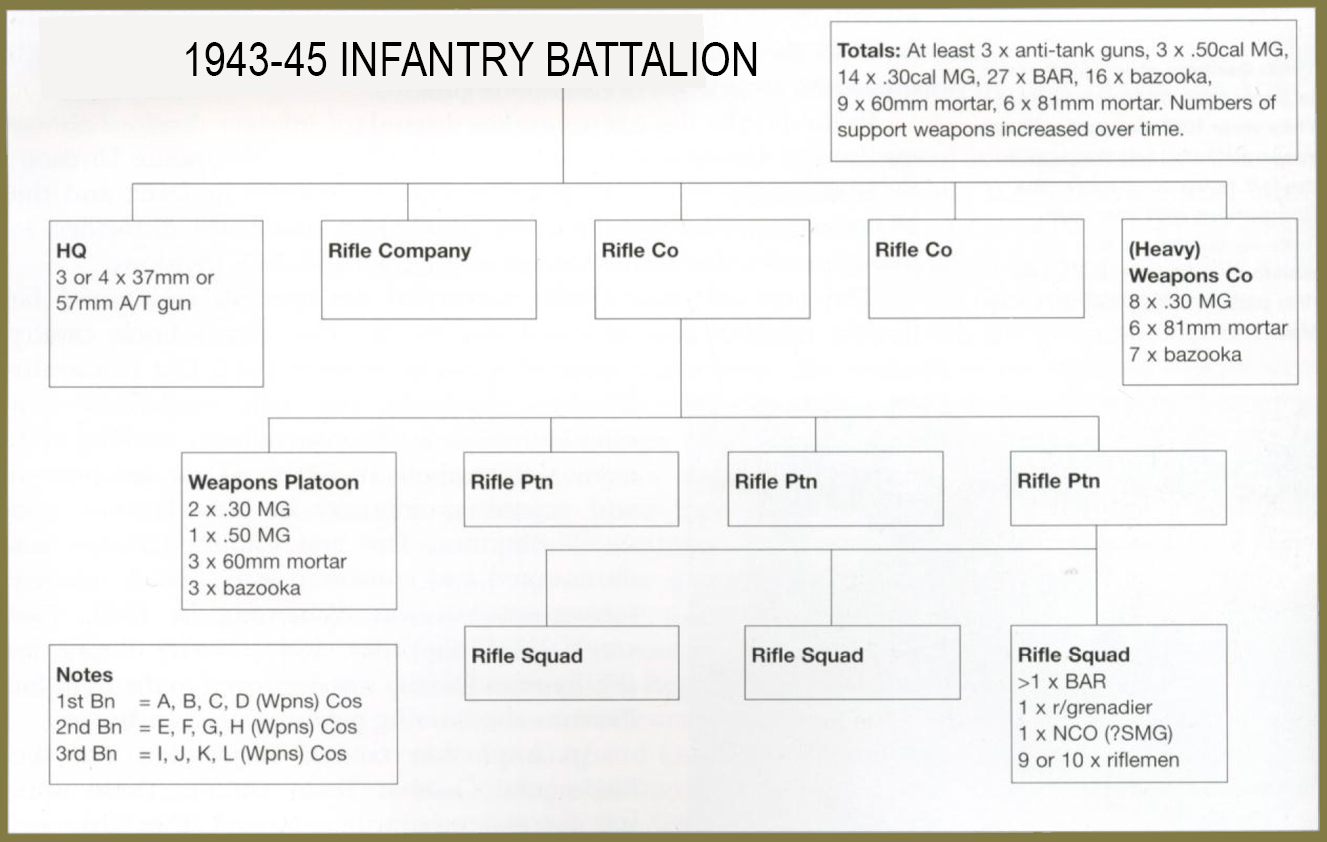

A 1943-45 infantry battalion consisted of 871 men in a headquarters, three rifle companies and a weapons company. Companies were 187 strong and consisted of three rifle platoons and a weapons platoon. A company was commanded by a captain, a rifle platoon by a lieutenant or sergeant. By 1943-44 a battalion (heavy) weapons company had eight machine guns, six 81mm mortars and seven bazookas. The rifle company's weapons platoon had two .30cal machine guns and one .50 cal, three 60mm mortars and three bazookas. Battalion HQ initially had three 37mm (later 57mm) anti-tank guns; by 1944 these were usually consolidated at divisional level.

At full strength, each of the platoon's three rifle squads consisted of 12 men and was led by an NCO. It was supposed to have ten riflemen, a rifle grenadier (armed with the 03 Springfield rifle), and a Browning Automatic Rifle man, providing the squad's light automatic support fire. Once in combat this configuration soon broke down, and GIs carried what was expedient and available. A squad might commonly add or substitute a 'tommy-gunner', a bazooka or an extra BAR man.

The Army started the war in khaki and brown drab uniforms and buff khaki (OD#9) webbing gear; by the end of the war olive drab (OD) green began to predominate. The term 'OD green' quickly came to mean any flat green colour from olive to dark green. The official shade (OD#7) was a darkish green characteristic of vehicles, 1943-45 combat clothing and web gear.

Khaki service dress ('chinos')

Khaki cotton shirts and trousers were standard Class C issue throughout the war for wear in summer and in hot climates ('khaki' is used throughout this text in its American meaning of a pale sand colour, equivalent to British 'khaki drill'). They were worn all year round in the South Pacific. The long-sleeved shirt had a six-button front and two breast pockets with clip-cornered straight flaps. lies, when used, were black (M1936 and M1940) or more commonly khaki gaberdine/cotton (from 1942), and were worn tucked in below the second shirt button. Officers' shirts differed from the enlisted men's (EM's) version in having shoulder straps ('epaulettes'); an officer's khaki gaberdine shirt was also available as a private purchase. Some officers' shirts had square pocket flaps, some pointed or three-pointed. The matching trousers were straight cut. with slash side and rear hip pockets. An inch-wide khaki webbing belt with a bronze open-frame buckle was used with the EM's trousers; officers' belt buckles had a smooth brass face plate. Long khaki shorts were also authorised but rarely worn.

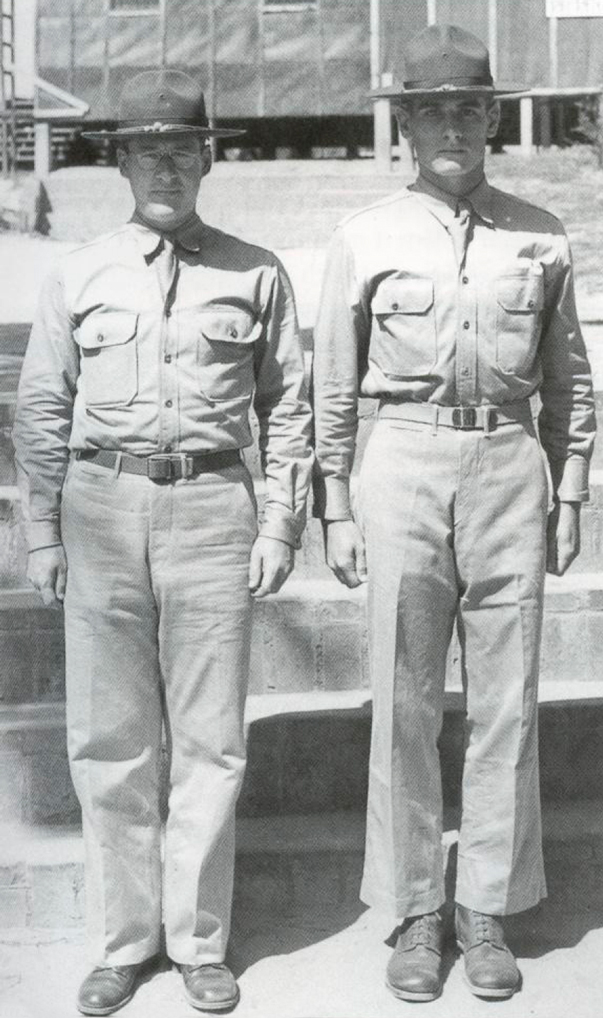

A clear view of two garrison privates in khakis, c1941. Note the creased trousers, tucked-in ties, and campaign hats with coloured hat cords; enamelled metal unit crests were commonly worn on the front of these hats. They would soon be supplanted by khaki overseas caps. It was not uncommon, if somewhat provocative, for enlisted men to wear officers' quality items; the private on the right wears an officer's buckle.

An officers' khaki cotton four-pocket service coat had been in use prior to Pearl Harbor. In September 1942 a khaki gaberdine version, with a slightly synthetic appearance, was authorised for officers; some early examples of this coat had a cloth belt. In the CBI, officers commonly wore variations on British khaki four-pocket tropical/bush jackets with US insignia added.

The visored khaki service hat (M1938) was standard issue before the war, but its issue was reduced in favour of the overseas cap (also commonly referred to as a garrison cap). This sidecap, inspired by British and French models, was first issued in the mid-1980s. It was later piped along the top and front edges of the turn-up curtain in branch of service colours (e.g. infantry, light blue); but by 1943 the EM's version was usually unpiped. Unit crests were sometimes pinned to the left front. Officers wore the same cap as the enlisted men but with mixed black and gold piping in place of branch colour, and with rank insignia pinned on the left front; general officers' caps were trimmed in gold.

In 1941, the Army's prewar Montana-peaked M1911 field/campaign hat also became a limited issue only, in favour of the overseas cap. A regimental crest was mounted on the centre front of the campaign hat; enlisted ranks wore branch-coloured hat cords, and officers mixed black and gold cords. This hat was sometimes worn with a narrow brown leather chinstrap.

Chinos were also intended as a combat uniform in hot climates but were rarely worn as such after the 1941-42 Philippines campaign. Khaki was rapidly found to be the wrong colour for battle, and the garments were entirely too lightly constructed. After the Philippines, it was agreed that the green herringbone twill work uniform was the only acceptable alternative for tropical combat.

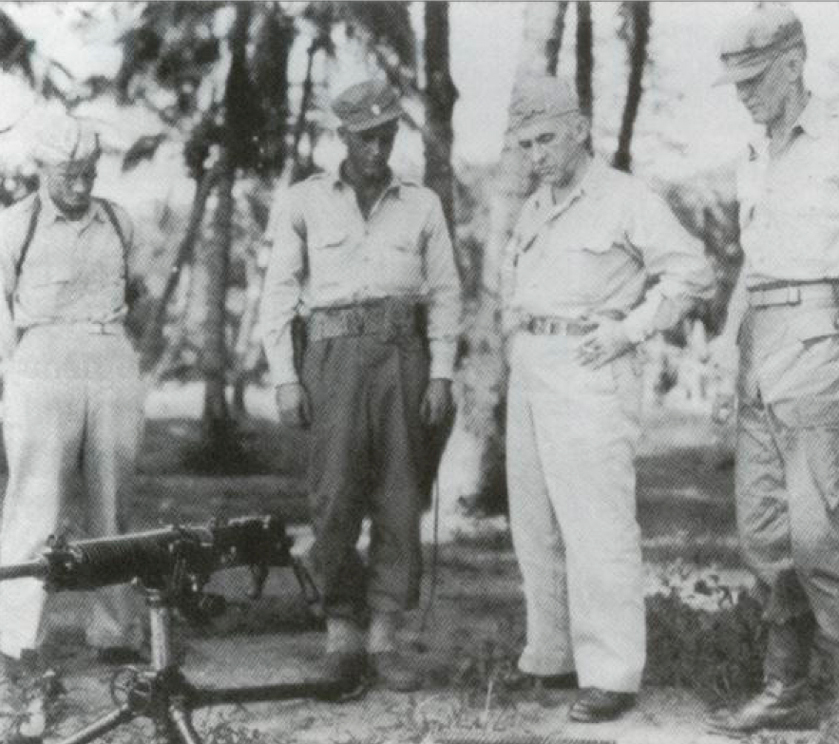

In a training area at Hollandia in 1944 the 6th Army's Gen Walter Krueger (second right) discusses the merits of a Japanese 7.7mm machine gun with members of the 'Alamo Scouts' - a long range reconnaissance unit which he raised late in 1943, and which carried out its first mission in the Admiralties the following February. The group show a mixture of khaki shirts (with insignia), overseas caps and trousers, with green HBTs and fatigue caps; note the long bill of the ('swing' type?) cap at far right.

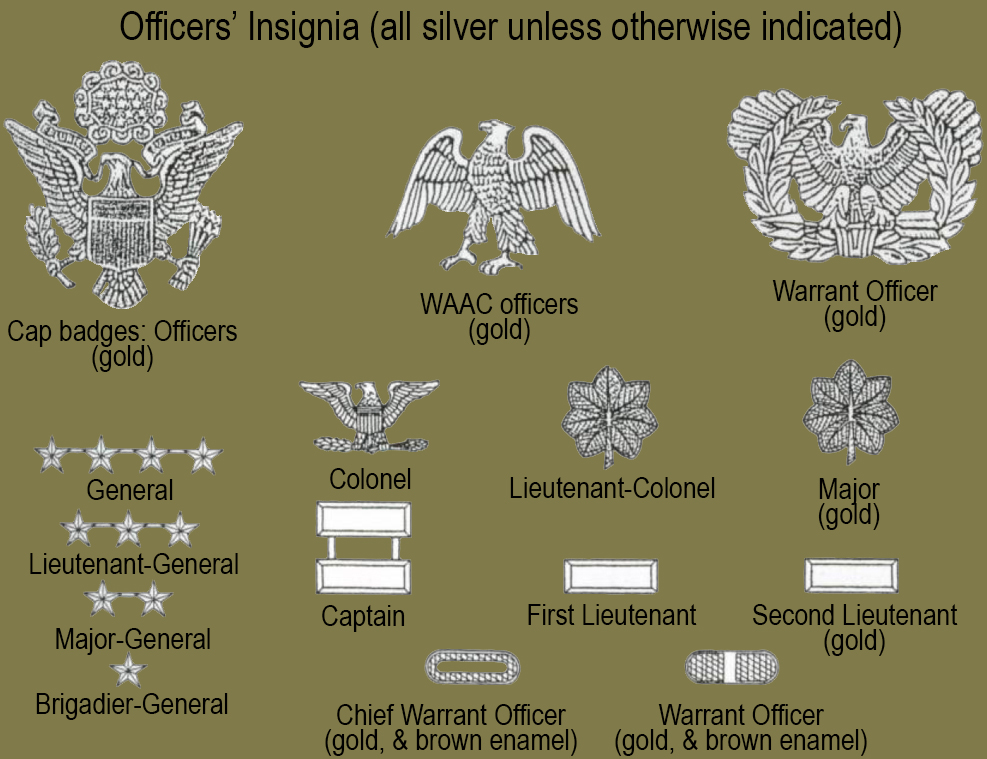

Officers pinned their rank insignia near the end of coat epaulettes or on the right shirt collar. They were usually removed in combat to avoid drawing attention; indeed, in the Pacific the activities of enemy snipers made the wearing of any insignia on the battlefield quite uncommon. Officers sometimes pinned their rank under their collars or pocket flaps. (In combat in the European theatre an officer might wear his rank and branch insignia on his shirt collar under cover of a plain jacket.) Woven rank insignia in dull silver or golden thread were used as well as the metal equivalents.

Company grade officers were warrant officers, second- lieutenants, lieutenants and captains; field grades were majors, lieutenant-colonels and colonels; general officers were brigadier-generals and above. Warrant officers ranked below second-lieutenants but were officers and were saluted by enlisted ranks. The grade was created to fill special technical jobs; they had most of the privileges of officer rank with limited specific responsibilities. Warrant officers were commonly glider pilots, ordnance and administrative specialists, etc; they wore a special pattern of hat eagle badge and rounded bars for rank.

The Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) was created in 1942 to provide additional 'manpower' to the Army in administrative and support roles. They had only semi-official standing within the Army. The WAAC used Army rank insignia but had special rank titles, e.g. 'second officer' or 'third officer' and 'leader' for the equivalent of lieutenants and sergeants. They were paid at a rate one or two lower than their equivalent military rank. In 1943 the WAAC was converted into the Women's Army Corps (WAC) and became official members of the Army with full pay. In addition to 100,000 WACs, a further 60,000 members of the Army Nursing Service and some 1,000 WASPs (Women's Air Service Pilots) served in the Army in World War II; nurses and WASPs used their own uniforms and insignia, though their uniforms and the WACs' were eventually aligned.

Women (WAACs/WACs) initially wore khaki shirts and below-the-knee skirts for summer; for athletics and fatigue use in the USA they also had a light-coloured seersucker exercise suit to be worn with the 'Daisy Mae' hat. Officers additionally had a khaki cotton coat. The first model of this coat (initially with a cloth belt) had short transverse shoulder straps, false breast pockets, and slash pockets near the waist. The second model, available in 1943, had normal epaulettes; this was also authorised for enlisted wear in 1944. By 1945 a cotton khaki shirt and trouser combination slowly became available. Except in extremely hot conditions, ties were always worn (tucked in). Brown laced low-heel shoes, an issue purse (handbag), and the infamous kepi-style 'Hobby hat' in khaki were worn with this uniform. By 1944 a WAC pattern khaki overseas cap was available.

A group of WACs in the USA, 1945. Except for the technical corporal (right), these women all wear either the one- or two-piece version of the women's HBTs in medium or dark green - note angled flaps on the thigh pockets - with the 'Daisy Mae' hat; The 'tech corporal' wears the new 1945 khakis designed expressly for women, with an overseas cap bearing a unit crest.

WAACs universally wore the helmeted head of Pallas Athena as the lapel insignia of their branch, and had a special plain eagle cap badge and button design. The later WACs wore either the Athena or the standard branch lapel insignia of their attachment, except in infantry and artillery assignments, when the Athena was worn exclusively. The WAC also replaced the rather sad-looking 'walking buzzard' cap badge of the WAAC with the standard US Army eagle.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com