GORDON WILLIAMSON, Illustrated by STEPHEN ANDREW

GERMAN MOUNTAIN & SKI TROOPS 1939-45

Only two of the German army's mountain units, 1.Gebirgs-Division and 6.Gebirgs-Division, took part in the French campaign.

1.Gebirgs-Division saw action in the opening phases, and the drive to and over the River Maas. They met no opposition; the division's only casualties were men accidentally drowned in a night crossing of the river. Not until a full week after the invasion did the division finally run into some French opposition, at Rocroi, but this was swiftly overcome.

As light infantry, the Gebirgsjäger usually qualified for the Infanterie Sturmabzeichen after completing three individual combat actions against the enemy. The badge is in white metal or zinc with a vertical pin-back fitting.

Also frequently won by Gebirgsjäger was the Close Combat clasp, shown here in its bronze (bottom), silver (centre) and gold (top) grades for 15, 30 and 50 days dose-quarter battle-action respectively.

On reaching the Oisne-Aisne canal, however, the Gebirgsjäger ran into stiffer resistance and came under heavy artillery bombardment. It was forced onto the defensive for about a week. On 5 June, after a massive German artillery barrage on the French positions, 1.Gebirgs-Division crossed the canal and attacked the French. The resistance was determined, and the French launched immediate counter-attacks. However, the disciplined and determined Gebirgsjäger were able to throw back every attack by their opponents, French colonial troops from Morocco, and eventually the French were forced to retreat; the Gebirgsjäger set off in pursuit. By 7 June the division was crossing the Aisne, and enemy resistance was rapidly crumbling.

It was decided to withdraw the division and send it south to Lyons to hit the rear of the French forces battling the Italians, but the French agreed armistice terms before the division reached its objectives; instead of seeing further action, it went into a period of occupation duties on the border with Switzerland.

It is interesting to note that 1.Gebirgs-Division was selected to become part of the German force which was to have invaded Great Britain in Operation Sealion. After this plan was abandoned, it was to have supplied troops for the intended operation to capture Gibraltar.

The 6.Gebirgs-Division, newly formed, was only able to take part in the very last stages of the battle for France; its duties in this area consisted mainly of occupation service after the armistice.

Following Mussolini's rash decision to invade Greece, in 1940, and the subsequent setbacks his army suffered, especially once British reinforcements had arrived to assist the Greeks, Hitler was unwillingly drawn into the Balkan conflict. Among the divisions committed to the attack in the Balkans in April 1941 were four mountain units: 1.Gebirgs-Division took part in the attack on Yugoslavia, launching its strike from its base area in the Austrian province of Carinthia, 4.Gebirgs-Division also attacked Yugoslavia from a launch point in Bulgaria; and 5. and 6.Gebirgs-Divisions took part in the invasion of Greece as part of XVIII Gebirgskorps, their task being to smash the Greek defensive system, the Metaxas Line.

The Greek defences posed considerable problems for the Gebirgsjäger. They were well built, well armed and manned by fanatically determined Greek troops. The Gebirgsjäger launched their attack on 6 April. Despite a furious artillery bombardment supplemented by dive bombing attacks from Stukas, by no means all of the Greek strong-points had been neutralised, and the Germans were forced to take out each pillbox individually. This proved a long and costly process for the lightly armed Gebirgsjäger. Even when positions were finally captured, the Greeks would often put in determined counter-attacks, and it took 5.Gebirgs-Division four days of bitter fighting before they overran the Greek defences.

The 6.Gebirgs-Division was more fortunate, and punched its way through the Greek defences within a single day. The divisions then linked up and fought their way south towards Corinth, against units of the British expeditionary force. By 26 April Athens had fallen; the last of the British forces were withdrawn towards the sea ports of the Peloponnese and evacuated.

In Yugoslavia 1. and 4.Gebirgs-Divisions fought against a determined Yugoslavian defence in dreadful weather conditions, but the overwhelming strength of the German forces soon saw the Yugoslavs crushed. The total subjugation of Yugoslavia took just 12 days, and both 1. and 4.Gebirgs divisions played a major part in that success, and were congratulated by Hitler himself for their achievements.

The last major engagement in the Balkans in 1941 to involve Gebirgsjäger was the invasion of Crete. General Ringel's 5. Gebirgs-Division was to be transported to Crete (once the Luftwaffe's Fallschirmjäger had been dropped) in a motley flotilla of Greek fishing boats. Unfortunately they were intercepted by British warships, which wreaked havoc on the convoys of small wooden-hulled vessels; losses were considerable.

In the group photograph taken on the Eastern Front, the Oberfeldwebel in the centre appears to be wearing the anti- partisan badge in silver on his left breast pocket. Gebirgsjäger often found themselves in action against partisan units, especially in the Balkan theatre. (Ian Jewison)

The anti-partisan badge, bronze grade, awarded for 20 individual days combat against partisans.

A second attempt to land Gebirgsjäger on the island was made, this time by air. The mountain troopers were landed at Maleme on 22 May by JU 52 transport aircraft. (The transports were forced to land, under fire, on an airstrip littered with the remains of wrecked aircraft.) Once the area around Maleme had been secured by joint Fallschirmjäger/Gebirgsjäger forces, a Gebirgsjäger Kampfgruppe was despatched to drive the New Zealand defenders from the mountains around the airport. After much bitter fighting, which often involved hand-to-hand combat, the Gebirgsjäger began to gain the upper hand, and by 23 May the heights were in German control. With the airport no longer under enemy fire, the Germans could bring in reinforcements, including artillery and heavy equipment. The following week was spent in pursuit of the retreating British and Commonwealth troops who, it seemed to the Gebirgsjäger, were prepared to contest every metre of ground. The New Zealanders, in particular, were to prove determined enemies, and their pugnacious defence cost the Germans dear in casualties. The outcome of the battle was no longer in any doubt, however, and by 31 May those British and Commonwealth troops who had not been evacuated by sea surrendered to the Germans.

When Operation Barbarossa was launched, in June 1941, the Gebirgsjäger were to play a major part in operations both in the southern and the far northern fronts; in the north, in particular, Gebirgsjäger were prominent among the troops.

Hitler allocated Gebirgskorps Norwegen and XXXVI Korps, together with three corps of the Finnish army, to launch a drive towards the vital port of Murmansk. Gebirgskorps Norwegen was to attack towards the port itself, while the other two corps were to cut the rail link from Murmansk into the Russian heartland.

The terrain in this sector was appalling, comprising a mixture of barren rock and swampland in the north and dank, dark forests to the south, both heavily infested with mosquitoes. The Finns could scarcely believe that the Germans would wish to conduct a campaign in such an area, but Hitler insisted.

Gebirgskorps Norwegen, comprising 2. and 3.Gebirgs-Divisions, made rapid progress at first, despite the atrocious conditions, and smashed through the Russian defences, reaching the River Liza at the beginning of July. By this time, however, the Russians were receiving considerable reinforcements, and the Germans began to meet stiff opposition. The momentum of the advance was slowed drastically and the whole offensive in the north began to falter.

The Russians quickly put in a powerful counter-attack and while this was rebuffed by the Gebirgsjäger, the German advance ran out of steam. With winter approaching, 3.Gebirgs-Division was withdrawn and replaced by 6.Gebirgs-Division.

Further to the south, SS-Kampfgruppe 'Nord' fighting as part of XXXVI Korps, was about to take part in its first major battle. The SS troops had insufficient training and the division was sorely lacking in experienced NCOs. When the SS troops ran into the strongly defended Russian positions, losses were heavy. Where elements were led by experienced officers, progress was initially good, but as soon as these officers became casualties, the advance lost all momentum and the Russians, sensing the German uncertainty, immediately counter-attacked and drove them back. In some cases the badly demoralised SS troops broke and ran. The objectives were eventually taken, but the success was largely due to the German and Finnish army troops on the flanks of the SS-Kampfgruppe.

With the coming of winter, the Soviets launched a major offensive. Although the Germans were severely battered and suffered heavy losses, the line held and over the winter months of 1941-42 a stalemate developed. Only minor skirmishing actions continued as both sides rebuilt their strength for the inevitable battles in the spring.

In early spring 1942, 7.Gebirgs-Division arrived in the far north sector as the Soviets launched their offensive - a combination of massive land forces and a seaborne assault behind the German lines, intended to cut them off. Only after bitter fighting were the Russians held. A second assault wave very nearly succeeded, but then the weather closed in with such ferocity that no further military action was possible. By the time weather conditions had improved, the Germans had had time to regroup and better organise their defences, and the Russian offensive failed. Most of 1943 in this sector of the front was spent in minor patrolling activities, both sides having turned their main attention to other sectors of the front.

The summer of 1944 saw fresh Russian offensives against the southern and central sections of the far north sector, but the final collapse was brought about by political rather than military means. In September 1944, the Finns concluded a separate peace with the Russians. The Germans now faced the possibility of attacks from the rear by their own erstwhile allies, and it was decided to pull all German troops in this sector back through Lapland and into Norway.

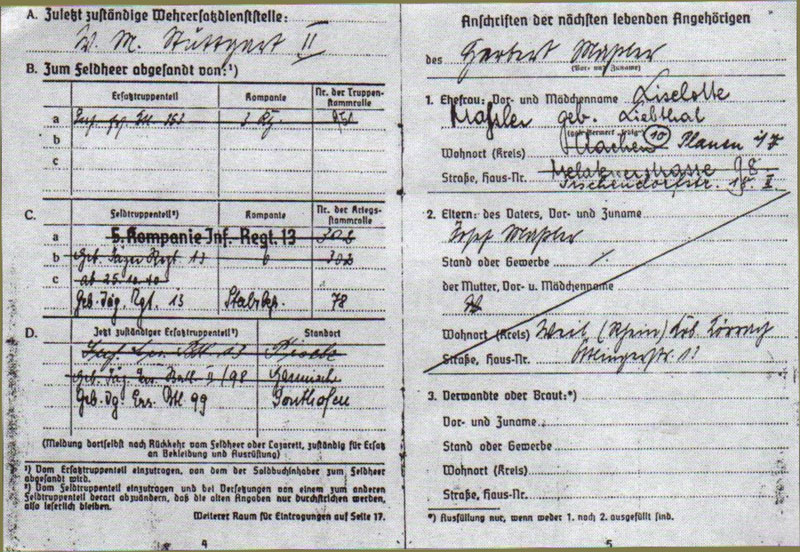

Page from Paybook (Soldbuch) of a Gebirgsjäger NCO, showing his unit attachments, this individual served with Gebirgsjäger Regiment 13, part of 1.Gebirgs-Division.

The Finns carried out several attacks on the retreating Germans, harrying them as they pulled back towards the Norwegian border, but had not the strength to cause the Germans any real problems. German activity on the far north of the Eastern Front had all but ceased.

Group of officers and senior NCOs, from the 'Prinz Eugen' division. Note cuff lilies and the Odal Rune collar patch on the officer on the extreme left.

On the southern sector of the front, in June 1941, 1. and 4.Gebirgs-Divisions had taken part in the rapid advances which followed the invasion, driving eastward towards the 'Stalin Line' defences. The attack on these Soviet defence lines by the Gebirgsjäger began on 15 July. After a massive artillery bombardment, the Gebirgsjäger stormed the enemy bunkers. The first line of defences were swiftly overrun, but the speed of the German advance, as on so many occasions, had left gaps in their line, and these were exploited by the Russians, who quickly mounted counter-attacks; bitter hand-to-hand fighting ensued in many places. By 16 July the Germans had penetrated the Stalin Line on a front approximately 15 miles wide. The Russians threw in numerous suicidal attacks, losing huge numbers of men in a desperate attempt to hold back the advancing Germans, while the bulk of the Red Army units withdrew to what they thought was the comparative safety to the east of the River Bug. Indeed, large numbers of Red Army troops made it over the Bug.

By mid-July, however, XLIX Gebirgskorps had crossed the Bug in pursuit of the retreating Russians, before beginning the drive towards Lilian. To the north of the Gebirgsjäger, 1.Armee smashed its way forward to Kiev before turning south towards Uman, and in the south 17.Armee, with 1.Armee, formed a gigantic pincer movement that was intended to close behind Uman and encircle the Russians who were retreating before the advance of XLIX Gebirgskorps. This was no simple 'round-up' of a fleeing enemy: the Soviet forces in the Uman pocket were enormous and made concerted efforts to break out but the German lines held and only a small number of

Red Army troops escaped. This was one of the great encirclements of the war in the east, with around 100,000 Red Army prisoners taken, over 20,000 of them by the mountain troops of XLIX Gebirgskorps.

The latter then pushed on towards Stalino, which was captured in the November, before advancing to positions by the River Alius, where they dug in as winter approached.

In July 1942 the Gebirgsjäger took part in a drive south into the Caucasus mountains. German troops in this sector were too few and too widely spread, however, and although Gebirgsjäger succeeded in scaling the highest peak in the Caucasus range. Mount Elbrus, and planted the German flag, powerful Soviet defences prevented much further progress and the massive Soviet counterattacks which ensued forced the Germans to withdraw. By the end of the year 1. and 4.Gebirgs-Divisions had pulled back into the marshy lands of the Kuban region, a virtual cul-de-sac from which they barely escaped when the Russian offensive in the south was launched following the debacle at Stalingrad.

Meanwhile, on the Leningrad front, 5.Gebirgs-Division had arrived fresh from its victory in Crete and was put into the line in April 1942, occupying that gloomy, heavily wooded swampland around the River Volkhov. Its prime task was to prevent the escape of Red Army units from the Volkhov pocket.

Fragmented remnants of a number of Red Army units did manage to escape into these great forests, and the Gebirgsjäger had the task of hunting them down through the summer of 1942. As winter approached, the fighting decreased somewhat in intensity, but in the late spring of the following year a massive new Soviet offensive saw the division fragmented as it was battered by hugely superior enemy forces. At the end of the year, 5.Gebirgs-Division was withdrawn and transferred to the southern sector of the front.

A fascinating anil unique presentation casket for the Knights Cross of the Iron Cross in the shape of a mountain-boot, presented to General der Gebirgstruppe Böhme by 7.Gebirgs-Division. The casket has a bronze finish. (P. Pleetinik via F.J. Stephens)

A further view of the presentation casket awarded to General Böhme, with the lid removed to show the Knights Cross. (P. Pleetinik via F.J. Stephens)

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com