GORDON WILLIAMSON, colour plates by RON VOLSTAD

AFRIKAKORPS 1941-43

So many battles of the Second World War were fought with such ferocity and disregard for basic humanity that many survivors of that time have only the most bitter memories of their wartime experiences. The campaign in North Africa between September 1940 and May 1943 holds not only an enduring fascination for postwar generations; but also a perhaps unique degree of nostalgia for some surviving participants. The campaign was no less costly in terms of human lives and material than many others; but regret at the cost is accompanied by positive memories in the minds of many veterans. This is not to suggest that the dead have been forgotten; but an almost mystical bond nevertheless exists, even between former enemies, amongst veterans of the desert campaign. Their memories seem to have a special quality not found among men who fought on other fronts, and enduring hatred is very rarely voiced.

This can in some ways be explained by a number of contributory factors. Firstly there is the mystique of the desert itself. This was a vividly inhospitable battlefield, where the scorching, arid terrain by day became an equally unwelcoming, freezing world at night; where raging sandstorms could completely alter a landscape within just a few hours; and where countless flics, scorpions and sand vipers, to say nothing of open sores, jaundice and dysentery, could make life a complete misery. Soldiers of both sides suffered equally in this merciless environment, a factor which would certainly engender a common bond.

Secondly, by virtue of the inhospitable terrain, the population of this part of the world is sparse; civilian casualties were light, and the combatants were usually spared the moral dilemmas inseparable from the conduct of war in densely inhabited regions.

The men of both Rommel's Afrikakorps and the British 8th Army came to feel part of an elite, and both sides developed a sense of esprit de corps second to none, born partly of their long experience of mastering an isolated environment which demanded total self-reliance from European armies.

The Desert Fox': Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, 19442. He wears the field grey and dark green Schirmmütze, with gold general officer's distinctions, from the continental uniform (a phrase used throughout this hook to identify the regulation European clothing of the German forces). The tunic is that of a fine-quality lightweight tobacco brown wool tropical uniform, as privately acquired by senior officers and instantly recognisable by its open collar. At the throat Rommel wears his Knight's Cross with Swords and Oakleaves, and the Pour le Mérite awarded for gallantry in Italy in the Great War. Photos show that as a rule Rommel wore only these orders, his tunic being devoid of decorations.

Last hut not least was the fact that almost without exception, the war in the desert was fought 'cleanly', and there are countless talcs of humanitarian acts on both sides. The desert campaign was almost unique in this relative freedom from atrocity. Both sides were commanded by officers of the highest calibre, men who had the greatest respect for their opponent's capabilities - as indeed did the individual soldiers of each army.

Countless books have appeared on the subject of the campaign in North Africa from both sides. To cover all aspects of the battles, the commanders, the equipment, uniforms and insignia would require a massive work of many volumes. This small book will restrict itself to providing the reader with a basic- background knowledge of the Afrikakorps, its organisation, uniforms and insignia. For those who wish to study the subject in greater depth there arc numerous specialist works available; amongst the best are: Uniforms, Organisation & History of the Afrikakorps by R. J. Bender and R. D. Law (Bender Publishing); Rommel by R. D. Law and C. W. H. Luther (Bender Publishing); and Rommel's Army in Africa by Dal McGuirk (Century Hutchison Ltd).

German military involvement in North Africa was brought about as a gesture of support by Hitler for his incompetent ally Mussolini. The Italians, eager to share in Hitler's continuing military success, had invaded Egypt from their colony of Libya in September 1940, outnumbering the meagre British forces by some five to one. During the first major engagements, which began when the British Commander, Middle East Forces, Gen. Wavell, launched his originally limited 'Compass' offensive on 9 December, the Italians were dealt a severe blow to their strength and morale, losing vast numbers of prisoners. After the battle of Sidi Barrani, when the retreating Italian forces were cut off' at Buq Buq, their losses stood at 38,000 compared with 624 among the British Commonwealth troops.

German reconnaissance troops parade in Tripoli, February 1941; these motorcycle crews are probably from the recce battalion of 5th Light Division, Aufkl. - Abt. (mot) 3. They wear full regulation tropical dress including the unpopular pith helmet.

The Italians were pursued into Libya where a major force of some 45,000 was besieged at the fortress of Bardia by the Australians, surrendering on 5 January 1941 after their commander, Gen. Berganzoli, had left his men to their fate. The Italian commander fled to Tobruk where defences were hurriedly strengthened. On 21 January the allies attacked with scant but effective armoured support; and after a short but bitterly fought battle Berganzoli once again fled, leaving over 27,000 men of his garrison to surrender. Although near to exhaustion, the smaller Commonwealth force pursued the Italians relentlessly until, on 7 February, the enemy surrendered at Beda Fomm. Mussolini had lost a total of over 130,000 men and 380 tanks in just two months.

Hitler had offered Mussolini his assistance in the form of a German Panzer Division prior to the Italian invasion of Egypt, but the overconfident Italian dictator had declined. Now it seemed that without immediate German support the Italians would soon be driven out of North Africa altogether. The die was now cast and German involvement in the desert war was inevitable. Gen. O'Connor's Western Desert Force (from 1 January 1941, XIII Corps) of some 31,000 British and Commonwealth troops of 7th Armoured Division and 4th Indian Division, reinforced by 6th Australian Division and New Zealand troops, had decisively defeated the Italian 5th and 10th Armies, comprising some 236,000 men. Now, however, they would face an entirely different calibre of troops and commanders.

Rommel's first campaign, February 1941

The first German units arrived in Tripolis on 14 February 1941; they comprised advance echelon troops of 5 leichte Division and 3 Panzer Regiment as well as support units such as pioneers and reconnaissance troops. Fully motorised and with good quality armour, the German force was small but powerful. It was commanded by Generalleutnant Erwin Rommel, a respected and able soldier who had gained a high reputation during the campaign in France, where he commanded 7 Panzer Division.

Due to the perilous situation in Libya the German force was committed to the front immediately, and anti-tank defences were constructed. German reconnaissance troops soon established contact with the enemy, and before long Rommel became aware of the extent to which British forces had been overstretched and weakened by the exhausting if victorious campaign against the Italians. In addition, Wavell had lost some of his British armour and Australian and New Zealand troops to the campaign in Greece, and 4th Indian Division to Ethiopia.

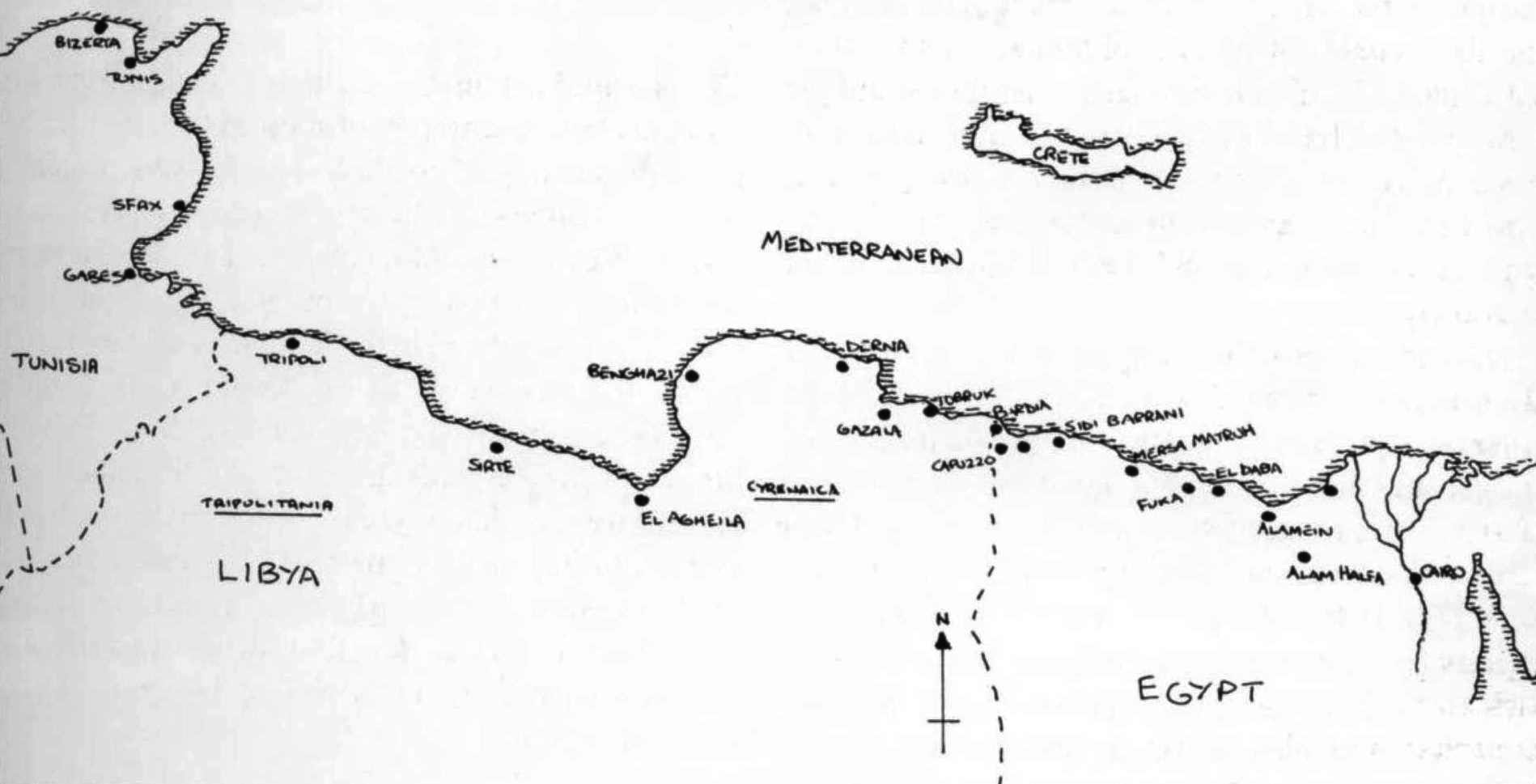

The North African theatre of operations - more than 1,300 miles from Tunisia in the west to the Nile delta in the east, with few towns, and those clinging to the single modern coastal highway. In the wide open expanses of the desert armies maneuvered like fleets at sea, occasionally clashing in vast set-piece actions at more or less predictable points where wrinkles in the geology gave some slight advantage.

DAK Panzer III tanks parade through an Italian colonial town. The arrival of modern armour, led by an energetic commander, transformed the desert war, which in winter 1940 had been an unbroken succession of British victories.

Rommel, living up to his reputation of missing no opportunity to strike at the enemy when the situation favoured him, struck towards the strategic supply port of Tobruk, attacking the British forces at El Agheila. The tide turned against the British as the fresh troops of Rommel's Afrikakorps pushed them back toward Mersa Brega. Despite orders not to undertake any ambitious major operations at this stage, Rommel decided to press home his advantage; part of 5 leichte Division was dispatched up the coast towards Benghazi while his Panzers, and the remainder of 5 leichte, pushed on across the desert to El Mechili.

On 4 April 1941 Benghazi fell, followed three days later by El Mechili; and one of Rommel's patrol units capturing Lt. Gen. Richard O'Connor and Gen. Neame. O'Connor was one of the best British field commanders at this stage in the war and his loss was a severe blow to the exhausted British forces. The bulk of 2nd Armoured Division were captured as Rommel relentlessly pursued his retreating enemy back towards Tobruk.

Tobruk itself was to be a different matter, however. With a strong garrison force of some 35,000 men including Australian troops of the inexperienced but determined 9th Division, Wavell was under orders to hold Tobruk at all costs. Even if cut off he could be resupplied by sea, as the Royal Navy still had control of the Mediterranean. Rommel's attack on this powerful garrison had little effect, particularly as he had divided his forces, sending some units on ahead to secure Fort Capuzzo, Halfaya Pass and Solium. His first attack on Tobruk was made by Pioniere, a Maschinen-Gewehre Bataillon and some elements of 5 Panzer Regiment. Despite the failure of the attack on Tobruk, however, Rommel had succeeded in driving the British out of Cyrenaica in just 12 days.

'Brevity' and 'Battleaxe', May-June 1941

In mid-May Wavell launched Operation 'Brevity' in an attempt to recapture the frontier positions at Halfaya, Solium and Capuzzo. These were taken, but the British were thrown out again just ten days later. In mid-June Wavell was persuaded by Churchill to launch another attack to relieve the Tobruk garrison and, reinforced by a large shipment of tanks and fighter aircraft, he launched Operation 'Battleaxe' on 15 June. Wavell's forces attempted to encircle the German positions at Halfaya and attack from the rear. This offensive lasted only three days. The British were shocked at the strong defence offered by the Axis forces at Halfaya, where the deadly 88 mm Flak guns were used in their equally effective antitank role. By 16 June Rommel's counter-attack had halted the British and began to roll them back. By 17 June the British had been pushed back into Egypt and the encircled Halfaya garrison relieved. British losses were heavy, with 91 tanks destroyed for the loss of only 12 Panzers. On 21 June Wavell was relieved, and passed his command to Gen. Auchinleck.

Following this ill-fated British offensive there was a period of several months of relative inactivity while both sides rebuilt their battered forces, Auchinleck preparing for yet another offensive to relieve Tobruk and Rommel establishing formidable defensive positions. The garrison at Tobruk continued to be supplied by sea. While the Axis were stronger in air power, the British still enjoyed naval superiority; at one stage as much as 62% of the Axis supply convoys were being lost to Allied attacks.

Rommel determined to launch yet another attack on Tobruk on 20 November. The Allies, however, were aware of Rommel's plans, principally through the 'Ultra' interception of coded radio traffic, and had precise details of Axis strength and positions. Auchinleck launched his own offensive, Operation 'Crusader', two days before Rommel's own planned attack on Tobruk, catching the Axis forces unawares. The British planned a sweep up through the desert in the area between the Egyptian frontier and Tobruk cutting off the Axis positions at Halfaya and Bardia and providing a launch point for the relief of Tobruk. British reinforcements had been arriving at a regular rate until, now, on the eve of the offensive, Auchinleck could field 736 tanks to Rommel's 240 Panzers; Rommel also had some 150 Italian tanks hut these were generally of such dubious quality that they could hardly be held to be a significant factor.

A medal award ceremony in the field. The troops wear the peaked field cap apart from the two honour guards, wearing steel helmets. All ranks seem to wear the high lace-up tropical hoot. (Josef Charita)

Panzer III tank crew in tropical shirts and shorts, two of them still wearing the black Feldmütze of continental uniform, the others peaked tropical field caps. If left note high laced boots; also a captured South African pith helmet, badged with German insignia.

Operation 'Crusader' began on 18 November 1941 when the newly redesignated 8th Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Cunningham and comprising XIII and XXX Corps, poured over the border. Opposing them were the Italian Ariete and Trieste Divisions in the Italian XX Mobile Corps and the German Panzergruppe Afrika, comprising the Deutsches Afrikakorps and the Italian XXI Corps. The Afrikakorps itself included the Italian Savona Division as well as 15 and 21 Panzer Divisions and 90 leichte Afrika Division.

The troops on Cunningham's right flank made good progress, with XIII Corps (the New Zealand and 4th Indian Divisions and 1st Army Tank Brigade) hooking around Sidi Omar towards Bardia. On the desert flank, however, XXX Corps (7th Armoured and 1st South African Divs., 4th Armoured and 22nd Guards Bdes.) failed to draw the Panzers into battle and became vulnerably dispersed. At Bir el Gubi 7th Armoured lost some 50 tanks to the stout defenders from Ariete Division. Cunningham's left flank forces eventually took Sidi Rezegh, only to be pushed back again by a massive Axis counter-attack when Rommel's Panzer Divisions smashed into the British XXX Corps from two directions. The British lost over 200 tanks.

The 'Crusader' battles see-sawed back and forth in three weeks of furious combat, with many targets being captured and lost several times. Just as the tide seemed to turn against the British, Rommel led a major part of his force racing towards the Egyptian frontier, hoping to cut off the British and attack from the rear. Whilst Rommel, with some 100 Panzers, rampaged around the British rear, isolated from the main battle and unable to draw the enemy into battle, the British grimly fought on. By drawing off such a large part of his mobile forces Rommel had surrendered control of large areas he had fought hard to win. By the time he realised that his 'Dash to the Wire' had failed and returned to his headquarters, the battle was once again beginning to turn against him. The Tobruk garrison had started to strike out eastwards, and on 26 November, New Zealand troops from XIII Corps met up with the Tobruk veterans at El Duda. Although the battle produced no outright winner, British losses (18,000 casualties and 287 tanks, against Axis losses of 30,000 and over 300) could easily be made up, while German resupply was becoming more problematic by the day and would continue to do so as long as the Royal Navy controlled the Mediterranean. On 6 December, therefore, Rommel broke oft the action and pulled his forces back from Cyrenaica to the Tripolitanian border, eventually forming a new front line back at El Aghcila at the beginning of January 1942.

All was not lost, however. Japan had entered the war, and the sudden need for both manpower and materiel in the Far East robbed Auchinleck of much-needed supplies and reinforcement. Additionally, winter conditions on the Russian Front had curtailed the bulk of the Luftwaffe's combat living, allowing the temporary transfer of considerable air strength for the North African front.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com