ANGUS KONSTAM, Illustrated by TONY BRYAN

BRITISH MOTOR TORPEDO BOAT 1939-45

Before 1935 the only British-built marine engine powerful enough to propel MTBs was made by Thornycroft (the 650hp RY 12). While Thornycroft continued to use these engines in their 55-foot CMBs, other companies looked elsewhere. Hubert Scott-Paine modified the 500hp Napier Lion aero engine for marine use, and used it to power his first British Power Boat MTB. He also modified the Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, and used them in a 70-foot prototype, bur the supply of these machines was threatened by the growing demand of the Royal Air Force. In September 1939 Scott-Paine arranged for American-built Packard V-12 1200hp engines to be used for BPB designs, but by that time his relationship with Elco meant that the engines were used in American boats, not British ones. Peter du Cane of Vosper opted for the Italian-built Isotta-Fraschini Asso engine, a lightweight V-18 design capable of 1,200hp. Thirteen engines were delivered before Italy declared war on Britain on 10 June 1940. Only MTBs 20 to 23, 29, 30, 71 and 72 were ever fitted with these superb engines. With the supply of Italian engines blocked, Vosper had to look elsewhere for its propulsion units.

Du Cane purchased the American-built Hall-Scott Defender 12 cylinder engine (650hp) for use in the next batch of Vosper boats, but the engines supplied from California were considerably heavier than their Italian counterparts, forcing a redesign of the 70-foot Vosper's engine room to accommodate the larger and heavier engine. Even when a supercharged 900hp version was introduced, the Hail-Scott engines were under-powered, and limited the boats fitted with them to a top speed of around 28 knots, compared to the 35-40 knots produced by the Isotta-Fraschini. The search continued for a lighter and faster replacement. The J. Samuel White company used Sterling Admirals, a supercharged British design available in limited numbers and capable of producing 1,120hp, while Thornycroft preferred to use its own engine design. British Power Boat continued to use a combination of British Scott-Napier 1,000hp engines, Rolls-Royce Merlins and Packards, but eventually the latter engine became accepted as the standard for their MTBs.

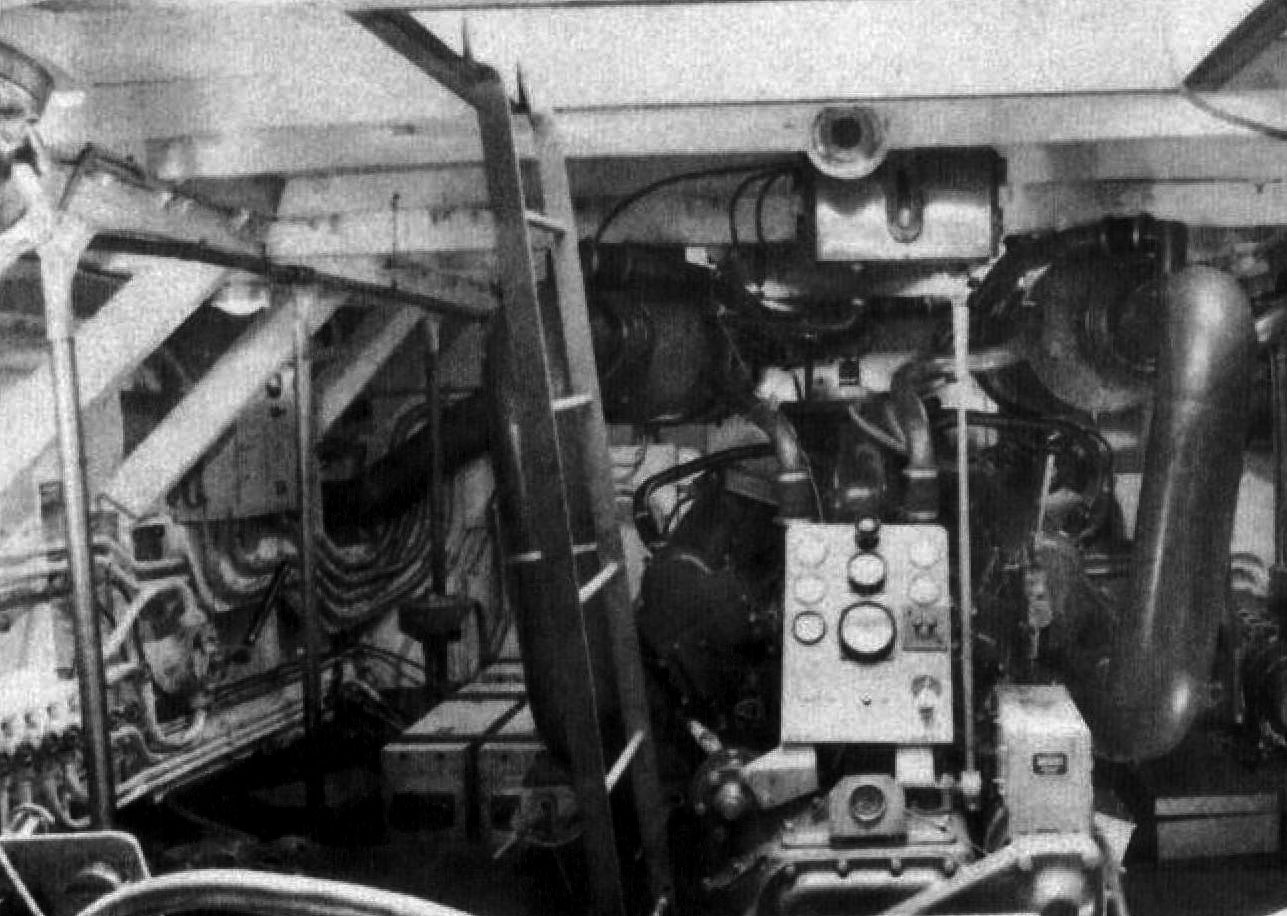

The engine room of the Thornycroft boat MTB 54, looking aft from the forward pair of engines. The boat was equipped with four RY 12 Thornycroft engines of 650hp each, powering two propeller shafts, giving it a top speed of 29 knots at 1,900rpm. (Vosper Thornycroft (UK) Ltd)

Vosper also settled on the Packard 4m-2500, a 12-cylinder supercharged engine capable of producing 1,200hp. The Packard Motor Car Company of Detroit, Michigan, was already producing marine engines for the US Navy's growing PT Boat fleet. Although heavier than previous engines, its added power overcame any displacement problems. Packard also had the production facilities to mass-produce these engines for export to Britain. In 1940 alone, 68 Packard 4m-2500 engines were delivered to Britain, allowing the replacement of Hall-Scott engines with the more powerful Packard designs. It also led to the modification of the standard Vosper design, resulting in the development of the 72-foot 6-inch boat. The development of the Lend-Lease programme ensured the steady supply of Packard engines, and by 1941 they had become the standard engine used in Coastal Forces. Refinements to the design were made throughout the war, and by 1942 the 5m-2500 entered service, an engine capable of producing 1,500hp. During the course of the war 4,686 Packard engines were acquired by the British, making the Packard the most widely used Allied marine engine of the war.

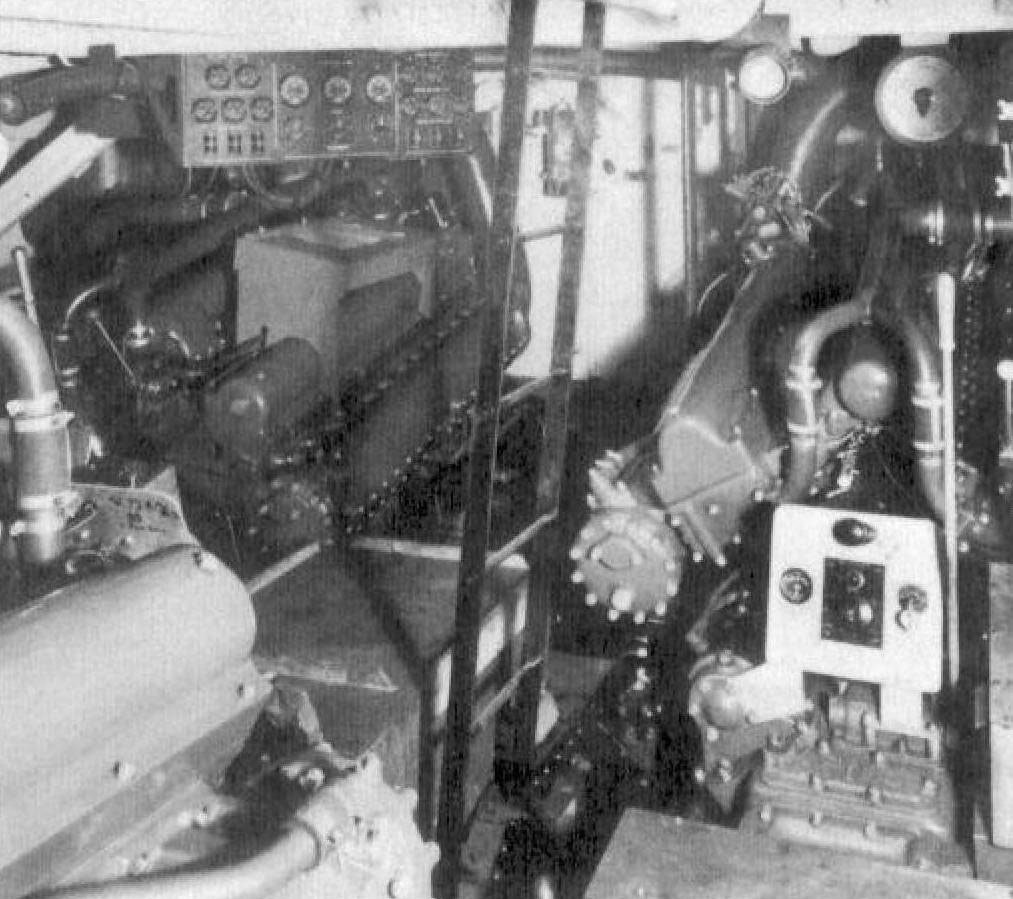

The engine room of a Vosper 72-foot 6-inch boat (MTB 351), photographed in April 1943, looking forward. The boat was fitted with three American-built Packard engines of 1,400hp each. The companionway leads up onto the quarterdeck. (Vosper Thornycroft (UK) Ltd)

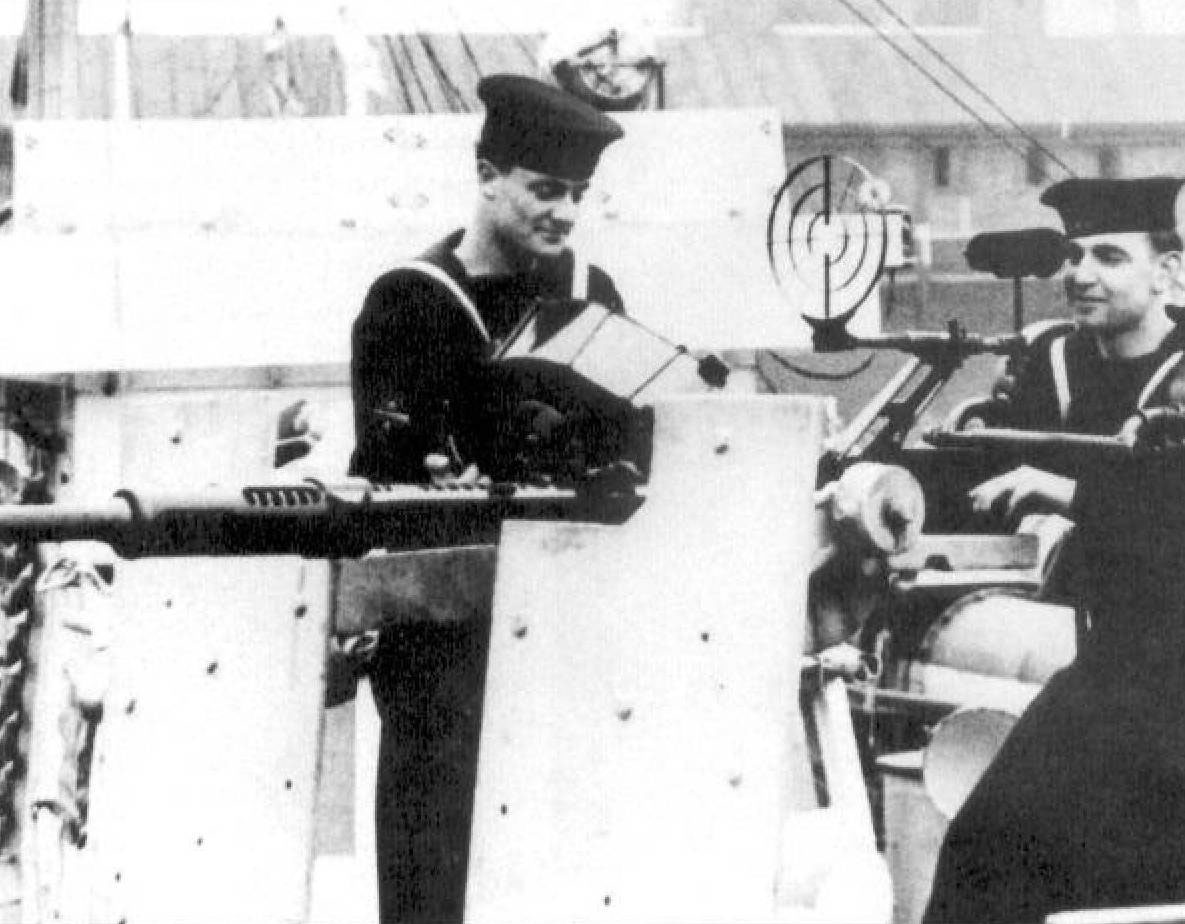

British Vickers Mark III .5-inch machine gun barrels after being removed from a 70-foot Vosper in either Lowestoft or Felixstowe. The guns had a rate of fire of about 650 rounds per minute, equivalent to a single box of ammunition. (Imperial War Museum)

Main engines were used while the boats were running at full speed, but silent-running secondary engines were also required when the boats were stalking their prey. The engine of choice was the Ford V8, which allowed the boats to cruise at up to 6-8 knots. These were then declutched and the main engine drive was engaged - a tricky process that was particularly fraught when the engines were crash-started in combat.

Clearly the main armament of these vessels was the torpedo. MTBs were not designed to engage in stand-up lire-fights with German surface warships such as E-boats and escort vessels. Instead their brief was to fire their torpedoes at a target, then escape. This said, the boats were armed with machine guns for close-range defence, and for anti-aircraft protection, and later in the war these vessels became increasingly heavily armed.

MTBs were armed with one of two types of torpedo: either the 18-inch or 21-inch version. American FT boats used only the 21-inch torpedo. The first torpedo systems fitted on Thornycroft 55-foot CMBs and BPB 60-foot MTBs were stern launch designs, where the 18-inch Mark VIII torpedo was dropped from a trough over the stern, activating the torpedo motor. The delivering boat then had to speed out of harm's way. The Admiralty and Vosper worked together to design deck-mounted torpedo tubes, where the torpedo was launched forward from a tube mounted on the side of the hull. In Vosper 70-foot boats these were angled outwards at 7½° from the hull, and a groove in the forecastle ensured the torpedo would fly clear of the ship's side. This led to a characteristic diamond-shape forecastle on early and mid-war Vosper designs. The 18-inch torpedo was used by the Royal Navy because of a shortage of 21-inch Mark XV torpedoes. Designed for aerial use, the 18-inch torpedo was 17 feet long, weighed 1,801 pounds and packed an explosive warhead of 545 pounds of TNT. Its steam turbine engine gave it a speed and range of 3,000 yards at 33 knots, or 2,500 yards at 40 knots. Depth settings could be varied from 4 to 44 feet, and the torpedo was designed to explode on contact. 18-inch torpedoes were used on BPB MTBs, 60-foot Vosper bouts, late-war 73-foot Vospers and Fairmile 'D' MGB/MTBs. Other boats carried the more powerful but heavier 21-inch torpedo. It measured 21 feet 7 inches, weighed 3,452 pounds and carried a charge of 722 pounds of TNT. A 21-inch torpedo had a range of 5,000 yards at 45 knots or 7,000 yards at 41 knots. Although the general trend was towards the standardisation of torpedo armament, the lighter 18-inch torpedoes and mounts found a new lease of life in late-war boats, where their smaller size allowed the fitting of up to lour tubes on one boat.

WRNS ('wrens') loading 21-inch torpedoes aboard MTB 234, a Vosper 72-foot 6-inch boat in Harwich, 1944. Wrens played a major part in the maintenance and support of British-based MTB flotillas during the war. (Imperial War Museum)

In pre-war Thornycroft and British Power Boat designs, close-range protection was provided by single or more often twin-mounted .303-inch Lewis guns (Mark I). Designed as an infantry support weapon just before the First World War, the Lewis gun had an effective range of around 400 yards, and a rate of fire of 550 rounds per minute. Ammunition usually came in 47-round drums, although 97-round drums were also available but in short supply. Lewis guns were normally fitted on pintle mounts, where they could be used against both aircraft and surface targets. By early 1940 the Lewis gun began to be replaced by the .303-inch Vickers gun (Mark V), a gun with a similar range to the Lewis gun, but roughly twice the rate of fire. Ammunition came in 10,000-round drums. Most Vickers .303-inch machine guns were mounted on pintles atop torpedo tubes.

A single 20mm Oerlikon on a Mark IIa (fixed pedestal) mounting, sited on the forecastle of a 72-foot 6-inch Vosper boat. The gun had a rate of fire of around 475 rounds per minute, and an effective range of 1,000 yards. (Private collection: Museum of Naval Firepower, Gosport)

The first Vosper boats carried a heavier machine gun, a .5-inch Vickers gun mounted in a Mark V turret. The Vickers was another weapon of pre-First World War vintage, but its water-filled cooling system permitted a sustained rate of fire of 700 rounds per minute, equivalent to a single 650-round ammunition box per minute. The Mark V turret was developed in 1939 by Marine Mountings Ltd, and allowed the gunner to control the twin Vickers machine guns with relative ease. It could traverse through 360° in five seconds, and elevate to its full 72° in a little over one second. The effective range of the guns was approximately 550 yards.

Despite the urgings of Lord Mountbatten and the successful deployment of a 20mm (.8-inch) Oerlikon gun on the Vosper prototype MTB 102, the Admiralty only began to issue these Swiss-designed guns to Coastal Forces during the summer of 1941. Although the initial priority was given to MGBs, the first Oerlikon-armed MTBs appeared in 1942, when the last 70-foot Vosper boats and 72-foot White MTBs were equipped with Oerlikons. The gun could fire either an explosive, tracer or armour- piercing round, with a rate of fire of approximately 470 rounds per minute. Although the heavy cylindrical magazine held only 60 rounds, it could be replaced in seconds, ensuring a sustained rate of fire. The usual MTB allowance per gun barrel was eight magazines. The effective range of the gun was 1,200 yards, but maximum range at its highest elevation (45°) was 6,250 yards at a surface target, or 6,000 feet at an aircraft. The Mark I single mount was replaced by a Mark IIa fixed-height pedestal mount, fitted to a stepped platform (which eased aiming at high elevation). The Mark IIIa and single Mark V mounts were variants on the earlier pedestal, while the Mark IV and Mark Villa mounts included a .5-inch steel gun-shield to protect the mounting. By 1943 the navy had introduced the Mark IX mount, which permitted the use of twin Oerlikons on the same pedestal. This hand-operated mount became the most common form of Oerlikon mounting used in MTBs by the end of the war, although the twin Mark V power-operated mount was developed by 1944 and used on some Fairmile 'D' MGB/MTBs.

A few MTBs carried even heavier automatic guns. MTBs 396 to 411 (77-foot Elco boats) and a handful of late-war US-built Vospers were fitted with a single Canadian-built 40mm Bofors gun on the stern. Its slow rate of fire (160 rounds per minute, and ammunition came in a four-round clip) was compensated by its effective range of 5,000 yards, and maximum altitude of 22,000 feet at 90°. The 2-pound Vickers QF ('Quick Fire') Mark VIII gun was fitted to BPB gunboats, then retro-fitted to several Vosper boats as guns became available. This 40mm 'pom-pom' had a rate of fire of 115 rounds per minute, but again, ammunition was limited to a four-round clip. Maximum effective range was 4,800 yards, or 13,000 feet at 70° elevation. Although this British weapon proved inferior to the Swedish-designed Bofors, it provided adequate close-range protection for MTBs when nothing better was available. Finally BPB MGBs converted into MTBs in 1944 and late-war 73-foot Vosper Type II MTBs carried a 6-pounder QF Mark II gun in a powered turret. This gun could fire 40 times a minute and had a maximum range of 6,200 yards, firing high-explosive or semi-annour-piercing rounds.

A single 20mm Oerlikon on a Mark IIa hand-powered mounting, fitted on the forecastle of the Vosper 72-foot 6-inch boat MTB 353. The splinter mattresses provided the gunner with some degree of protection while in action. (Imperial War Museum)

Finally MTBs relied on whatever firepower they could find. Depth charges were used against surface targets, dropping them in the path of enemy vessels. Their 400-pound charge could destroy almost any enemy escort or E-boat. The 2-inch Holman Rocket flare projectors could illuminate targets up to 2 miles away at night, and the Chloro-Sulphonic Acid (CSA) smoke-producing apparatus pumped out a cloud of white smoke which lasted for up to five minutes, allowing the MTB to escape under cover of the smoke. When all else failed, some of the most successful MTB commanders recommended opening up with whatever weapons were at hand, including pistols, flare guns, rifles, sub-machine guns and even hand grenades.

Motor Torpedo Boats were used in both home waters and the Mediterranean, but deployment further afield was curtailed after the loss of the squadron based in Hong Kong in December 1941, While their primary mission was the destruction of enemy merchant vessels, MTBs were often called upon to perform a range of duties, from escorting convoys, landing commandos or agents, patrolling areas of sea, or protecting amphibious landings. When the war began, the navy had devoted very little thought to MTB tactics, and operations were limited during the first eight months of the war. The fall of France and the entry of Italy into the war during mid-1940 meant that British Coastal Forces were suddenly involved in two campaigns for naval supremacy: one in the North Sea and English Channel, and the other in the Mediterranean. While space precludes a study of MTB operations in detail. Pope (1954), Cooper (1977), Reynolds and Cooper (1999) and Reynolds (2000) cover the operational use of British MTBs in detail (see bibliography). Instead, a brief examination of the practical use of MTBs in action is appropriate.

The first successful torpedo attack by an MTB was made in September 1940, some three months after the Germans began operating coastal convoys in the English Channel. This isolated success showed what could be achieved, but poor tactics and a lack of understanding of the capabilities of boats, crews and weapons prevented any further successes. Flotilla commanders began examining operations and discovered several errors that made any success unlikely. Firstly, boats were roaring into action at full speed, revealing their presence to German escort vessels and making targeting difficult. Secondly, commanders were firing their torpedoes at maximum range (around 3,000 yards), meaning that a hit was unlikely. Gradually crews learned from their mistakes or those of others, and a clearer notion of MTB tactics evolved.

The crew of MTB 48 discussing their attack on the German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau off Dover on 12 February 1942. The commander, Sub. Lt. Tony Law, is on the left of the photograph. (Private collection, Museum of Naval Firepower, Gosport)

The best way of attacking a target was to approach it at night under silent engines or even remaining stationary, letting the convoy approach the MTB. It was discovered that using stealth, boats could manoeuvre themselves to within 500 yards of a target vessel in moonlit conditions, and even closer on darker nights. Approaching an enemy from astern was another popular tactic, as it was less likely that enemy lookouts would be maintaining as vigilant a watch astern of their vessel. Once within range a boat would try to manoeuvre into an ideal firing position, to the side of the vessel, and just forward of the bow. This meant that the torpedo would hit its target at something close to right angles, increasing the chances of a hit. If a torpedo was spotted, the vessel would .also have the furthest possible distance to turn to evade it. Firing from the stern or bow quarters were the worst possible positions, as the target presented a narrow aspect, the risk of a glancing shot was increased, and the target could also manoeuvre away from the path of the torpedo with relative ease.

Once a torpedo was fired the silent engines would be de-clutched and the main engines thrust into gear. The MTB would then accelerate up to full speed, bearing away from the target and its escorts. While some commanders favoured the use of smoke to screen the departing boats, others found it a hindrance if a second torpedo run had to be made. Some skippers also favoured opening up with every available gun, hoping that the pandemonium would unnerve enemy gunners trying to hit the fleeing MTB. While the boat's radio operator called in reports of enemy strengths and positions (allowing other attacks to be made), controllers on the shore would then vector in other attacks, or send reinforcements to cover the retreating MTBs. At the start of the war MTBs were poorly armed, and had little chance of surviving a prolonged encounter with an enemy surface warship of any size. Instead it became commonplace to launch an attack, then to retire behind a screen of waiting MGBs, which could then protect the MTBs from enemy pursuers. As larger and more powerful deck guns became available, MTBs became better equipped to engage small enemy vessels such as E-boats, and sometimes attacks were made without the benefit of an MGB screen. Often these brief clashes between coastal forces were fought at point-blank range, and commanders resorted to firing any available weapon at enemy boats that came too close. Many commanders even carried a box of hand grenades on the bridge, and ready-use lockers of sub-machine guns for use by any crewmen who were not manning other weapons, conning the ship or operating the engines. Another tactic was to cut across the bow of an enemy vessel, then drop depth charges from the MTB, timed to go off at the shallowest possible depth setting. MTB commanders were playing a dangerous game, fighting at night, at point-blank range and in boats that were little more than high-speed mahogany and plywood fuel tanks. In a private war where a clip of 20mm shells or a single heavy gun round could virtually destroy an MTB, to loiter in the battle area after the torpedoes were fired was tantamount to suicide. In these fast and confusing actions, reflexes, experience, nerves and courage accounted for more than anything else. It is a tribute to the men who fought in these small boats that they succeeded in inflicting substantial harm on the enemy.

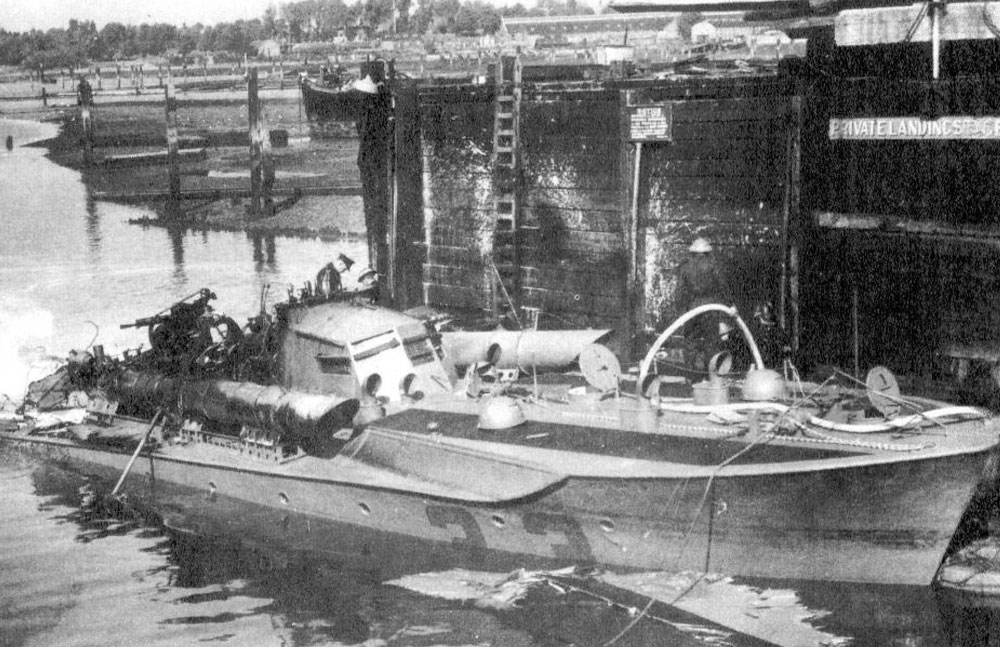

An early war casualty, the 70-foot Vosper boat MTB 33 was bombed by German aircraft while nearing completion at Portsmouth in September 1940. It is a testimony to the strength of its design that it still managed to float even when the stern was destroyed. (Vosper Thornycroft (UK) Ltd)

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com