RICHARD NATKIEL

ATLAS OF WORLD WAR II

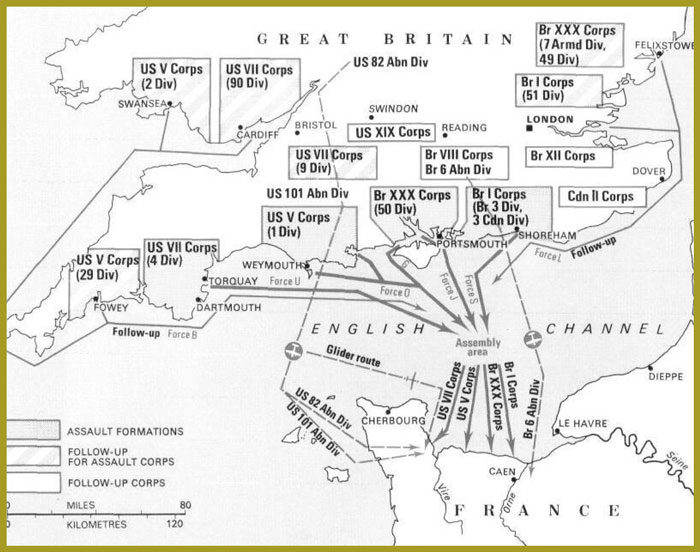

The main assault force consisted of the US First and the British Second Armies, with air support from the US 82 and 101 Airborne Divisions and the British 8 Airborne Division. These forces would land right and left of the target beaches to cover the landings. Two artificial ports (called Mulberry Harbors) would be towed across the Channel to permit the landing of tons of supplies before a port could be secured.

Elaborate plans were laid to deceive the Germans into believing that Pas de Calais was the intended target. A dummy headquarters and railroad sidings were built; dozens of sorties were flown over the area; while tons of bombs were dropped west of Le Havre.

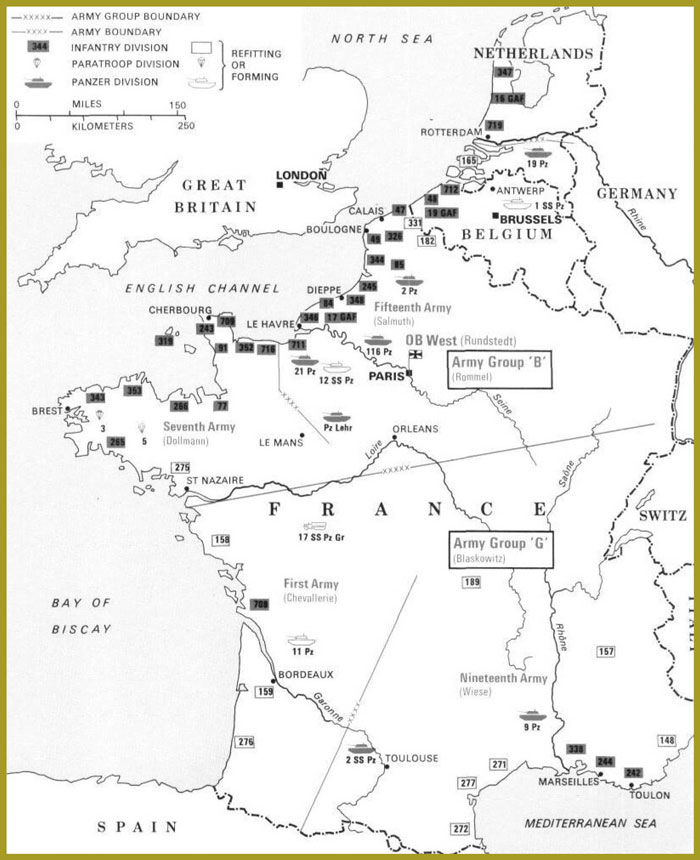

German forces guarding the coast of France consisted of Army Group B, commanded by Rommel, and Seventh Army under Dollmann. Hitler had a bad habit of bypassing von Rundstedt, Commander in Chief West, when he issued orders to his Army Group leaders, so the Germans had no effective chain of command in the west. Their position was further jeopardized by topography; destruction of the river crossings on the Loire and the Seine would isolate their forces in Normandy.

Nearly three million men made up the A Hied army and supporting forces ready for invasion.

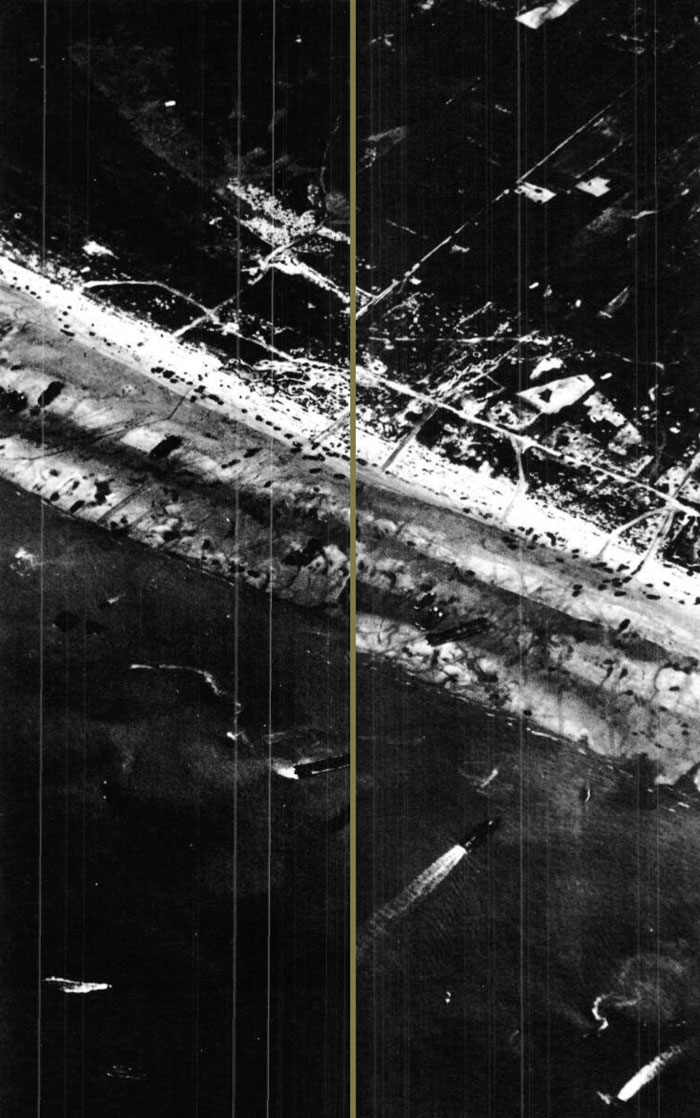

The first landings take place on the Normandy beaches.

The disposition of opposing German forces.

All the careful Allied planning that went into the invasion of France was subject to one imponderable - the weather. June of 1944 opened with unseasonable cold and high winds, which posed serious problems for the strategists. Optimum conditions of moon and tide occurred only a few days each month, and the first week of June comprised such a period.

Loading Allied wounded aboard a C-47 Dakota. Note the aircraft's black-and-white invasion stripes, adopted for easy identification.

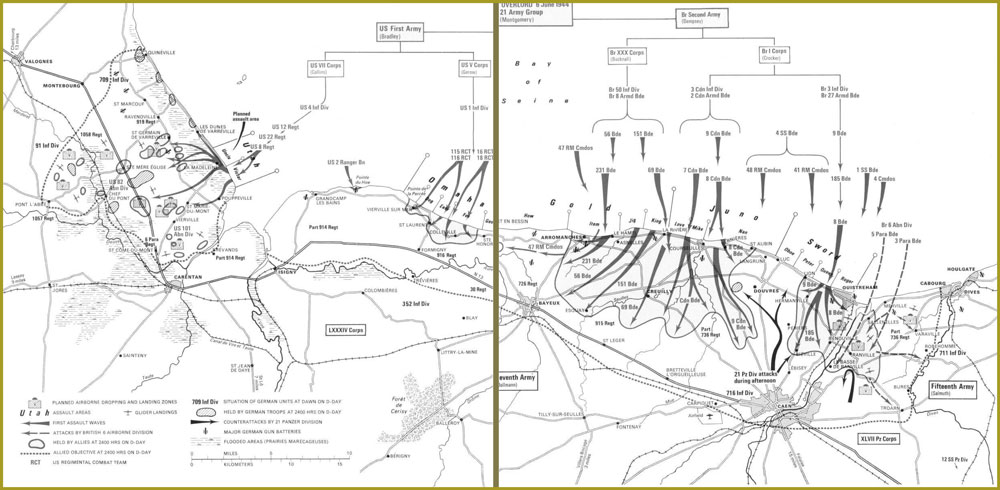

The invasion beaches.

General Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the operation, decided that the landings must go ahead on schedule. Then a fortunate break in the weather allowed the huge force to launch the largest combined operation in military history on D-Day - 6 June 1944. Three million men, 4600 transports and warships, and almost 10,000 aircraft were involved. General Montgomery commanded ground forces, Admiral Ramsay co-ordinated naval operations and Air Marshal Leigh-Mallory was charged with air support. Preparatory air attacks were particularly important in view of the shortage of paratroop- transport aircraft and the comparative strength of opposing ground forces - some half a million men of the German Seventh Army.

LCVP landing craft en route to the French coast.

Hitler himself contributed to Allied success by misusing the advice of two of his ablest generals to produce a compromise scheme that seriously hampered the German defense. Field Marshal von Rundstedt, Commander in Chief West, wanted to form a strong central reserve until the true Allied plan was known and then use it to repel the invasion, keeping beach defenses to a minimum. Rommel, commanding German armies in northern France and the Low Countries, cautioned that Allied air power would prevent Rundstedt's reserve from coming into action and recommended that the Allies should be defeated on the beaches before they could reach full strength. Hitler's compromise - strongly influenced by inflated reports of Allied manpower - neither strengthened the beaches sufficiently nor allowed for the flexible use of Rundstedt's reserve.

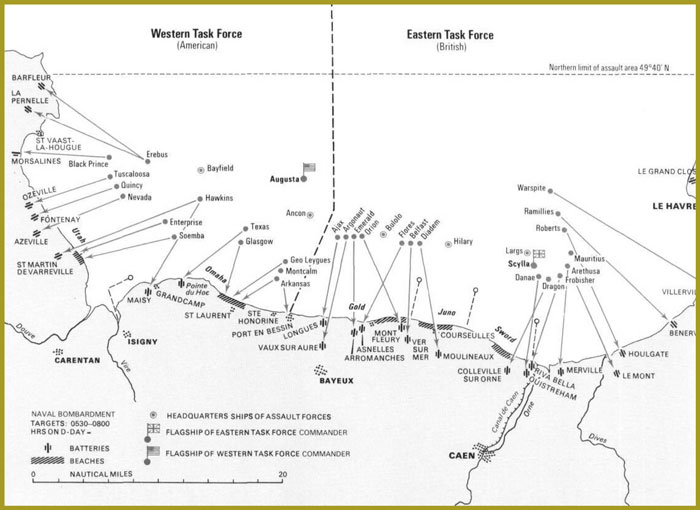

Five beaches were targeted for the Allied landings, code-named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword. At 2:00 AM on 6 June, US and British airborne forces descended on their objectives and consolidated a position within the hour. Tactical surprise was complete, thanks to the months of painstaking work by the deception team. An hour later, aerial bombardment of the beaches began, soon followed by fire from the 600 warships that had assembled off the coast. At 6:30 AM the first waves went ashore, US First Army on Utah and Omaha Beaches and British Second Army on Gold, Juno and Sword. Real problems were encountered only on Omaha, where landing forces were deprived of full amphibious tank support by rough seas. They were pinned down on the beach for hours, but managed to fight their way out to the coast road by nightfall. Within 24 hours, the Allies had achieved almost all their objectives for D-Day.

Disposition of Allied bombardment vessels on D-Day.

LST landing ships disgorge men and materiel.

A convoy of US Coast Guard landing craft (LCI) head for Normandy.

The Anvil Landings in Southern France

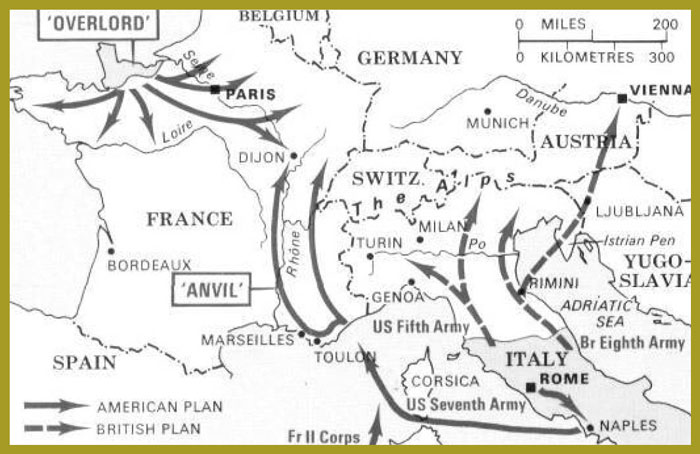

US and British leaders disagreed on the necessity of landing forces in southern France to support Operation Overlord on the Normandy coast. The Americans argued that such landings could open the much-needed port of Marseilles and draw off German troops from the north, but this could be done only by transferring troops from Italy. British leaders saw vast untapped potential in the Italian campaign and argued for pouring men and munitions into Italy to facilitate an advance over the Alps toward Vienna and the Danube. Stalin had his own vested interest in an Anglo- American effort as far west of Russia as possible, and he enlisted US President Franklin D Roosevelt's support. It was the American plan that prevailed.

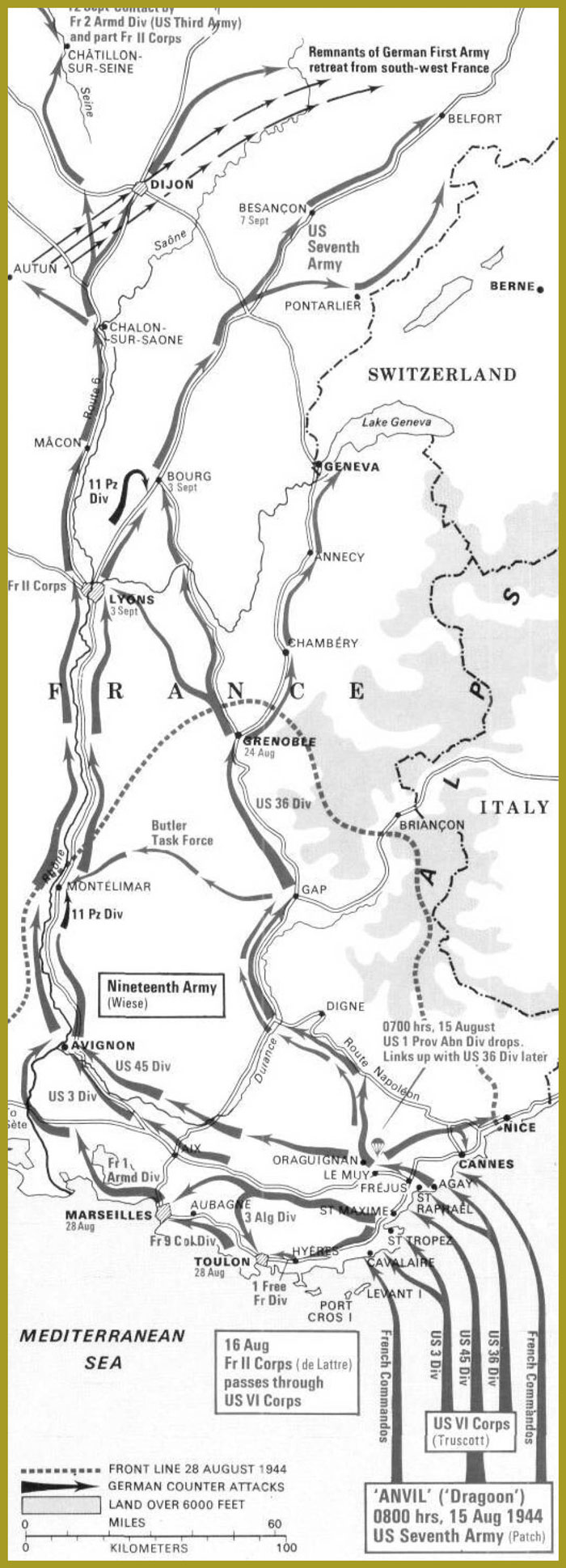

Operation Anvil was postponed from June 1944 - simultaneous with D-Day - to 15 August, due to a shortage of landing craft. On that date US Seventh Army made landings between Toulon and Cannes. Ninety-four thousand men and 11,000 vehicles came ashore with fewer than 200 casualties: all of southern France was defended by only eight German divisions. The French II Corps, under General de Lattre de Tassigny, then advanced toward Toulon and Marseilles, while US elements closed in on the German Nineteenth Army, taking 15,000 prisoners. De Lattre captured both his objectives, and US Lieutenant General Alexander Patch fought his way up the Rhone Valley to make contact with Patton's Third Army on 12 September. The newly formed French First Army then combined with US Seventh to form the US 6 Army Group under Lieutenant General Jacob Devers to drive into Germany on the right of the Allied line.

The Allied Breakout from Normandy

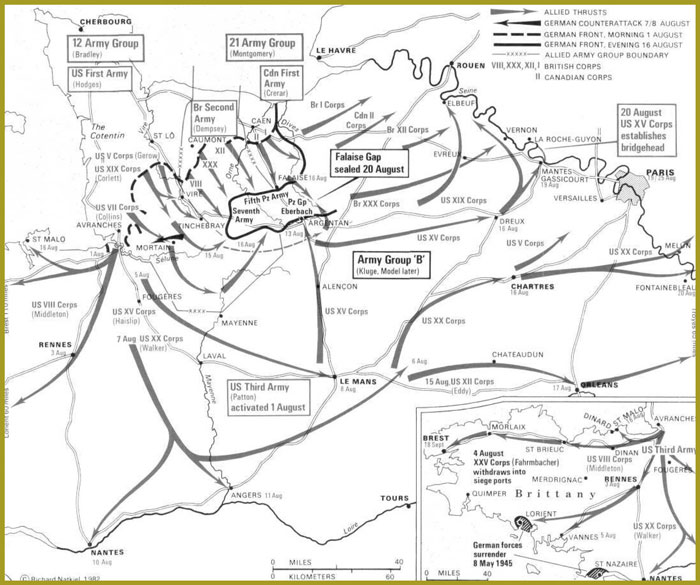

It took over half the summer for Allied forces to extend their initial beachheads well into Normandy, where Rommel had been reinforced from the south of France. Montgomery adhered to his original campaign plan and made slow but steady progress (although not enough to satisfy his critics, who were numerous). By 27 July (D+50), the Cotentin Peninsula was in Allied hands. Patton's US Third Army broke through the Avranches gap into Brittany and central France, and US, British and Canadian Forces attacked south and east in early August.

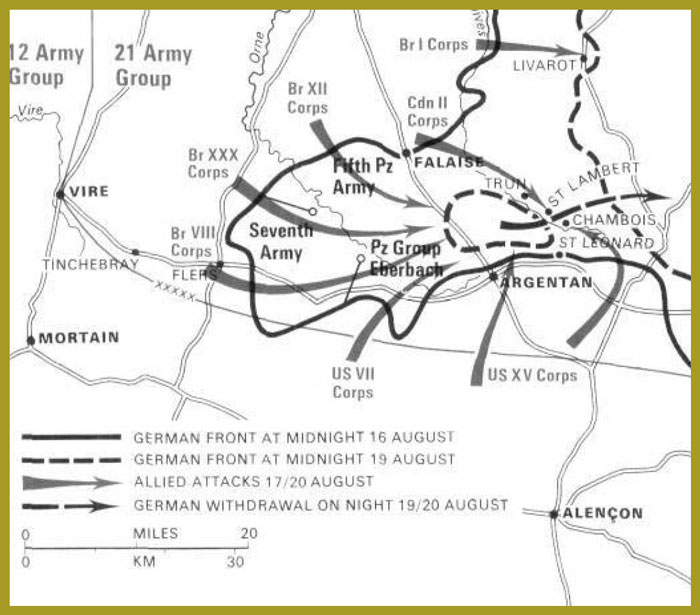

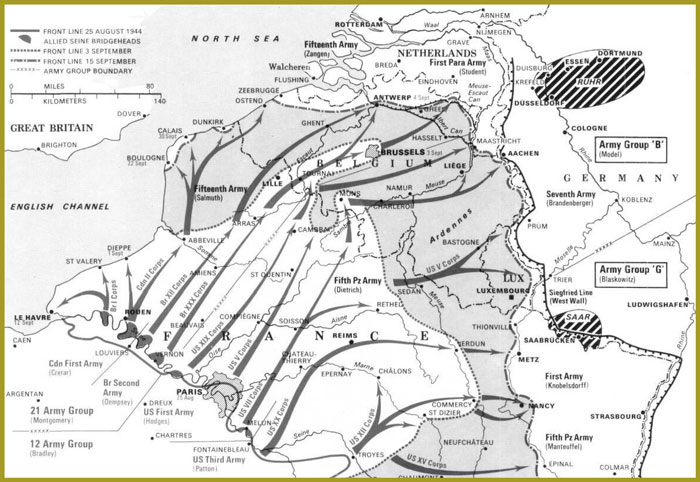

Hitler responded with orders for immediate counterattacks, which failed to contain the Allied advance. Both von Rundstedt and Rommel had been replaced in early July, and their successor, von Kluge, was pulled out on 25 August after four Allied armies pursued him to the Seine crossings. Patton's armor reached the Seine at Fontainbleu on the same day that US and Canadian forces closed the gap at Falaise, cutting off the escape of German Seventh and Fifth Panzer Armies. By this time, 10,000 German soldiers had died and 50,000 more had been taken prisoner.

The US XV Corps established a bridgehead downstream of Paris as soon as it reached the Seine, and five days later, on 25 August, the French capital was liberated. Kluge had succeeded in salvaging much of Army Group B, but his command was turned over to General Model by way of thanks.

Anvil, Overlord and the Britishplan over which they prevailed.

US troops drive the Germans from southern France.

Patton's Third Army pours through the Avranches Gap and sweeps south toward the Loire.

Pursuit and defeat of Germ an forces at the Atlantic coast.

US armor crosses the Siegfried Line en route for Germany.

The escape route for the Fifth and Seventh German armies ended at Falaise.

Reclaiming France and the Low Countries, summer 1944.

German soldiers pictured on the long march to captivity.

The remarkable achievement of Allied operations in Normandy should have been followed up, according to Montgomery and other strategists, by a narrow-front thrust into Germany to end the war in 1944. Eisenhower, who assumed direct control of ground forces in September as a function of supreme command, favored a slow advance in line by all Allied forces. The critical issue in August 1944 was that of supply: the logistics of providing food, fuel and other necessities to four Allied armies now 300 miles from the Normandy coast had become unworkable. A port was needed desperately.

Montgomery, Bradley and other narrow-front proponents argued for supplying part of the Allied force abundantly and sending it through Belgium to encircle the Ruhr and advance on Berlin at top speed. Eisenhower held out for a more cautious advance that did not underestimate the power of German armies still in the field despite their losses - 700,000 men since D-Day. There was far less risk in this approach, both strategically and politically. The disadvantage was in dragging out the war until 1945, which meant that the Russians would have time to establish their armies far west of their borders.

The Canadian First Army seized several small French Channel ports, and on 4 September the Allies captured the large port of Antwerp with its facilities almost intact. But failure to consolidate their grip on this valuable harbor immediately resulted in loss of control of the Scheldt Estuary, its seaward approach, to the Germans.

Arnhem and the Drive to the Rhine

Once Belgium was liberated, the Allies sought to secure a continuous northern ward advance by capturing a series of four bridges at key canal and river crossings. This would create a corridor through the Netherlands for a swing around the northern end of Germany's West Wall defenses (which were by no means as strong as the Allies supposed). Montgomery planned to drop three airborne divisions near the bridges at Veghel, Grave, Nijmegen and Arnhem in an operation that was hastily assembled under the code name of 'Market Garden.'

The 17 September landings at Veghel and Grave by US 101 and 82 Airborne Divisions were successful, and British XXX Corps linked up with these forces the following day. They captured the bridge at Nijmegen on 20 September, but were unable to make further progress. At Arnhem, British 1 Airborne Division was in desperate straits as a result of landing too far from the bridge in a strongly defended area. Only one battalion reached the objective, where it was immediately cut off, and the rest of the division was surrounded. Only 2200 survivors made it back to British lines; 7000 others remained behind to be killed, wounded or captured.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com