RICHARD NATKIEL

ATLAS OF WORLD WAR II

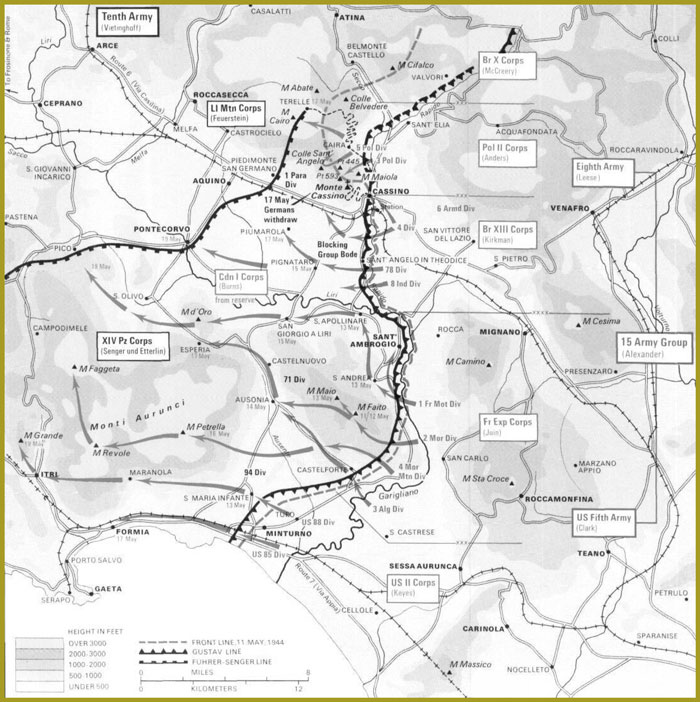

The second Allied offensive on the Gustav Line was somewhat more successful than its predecessor, pushing the Germans to the Führer-Senger line.

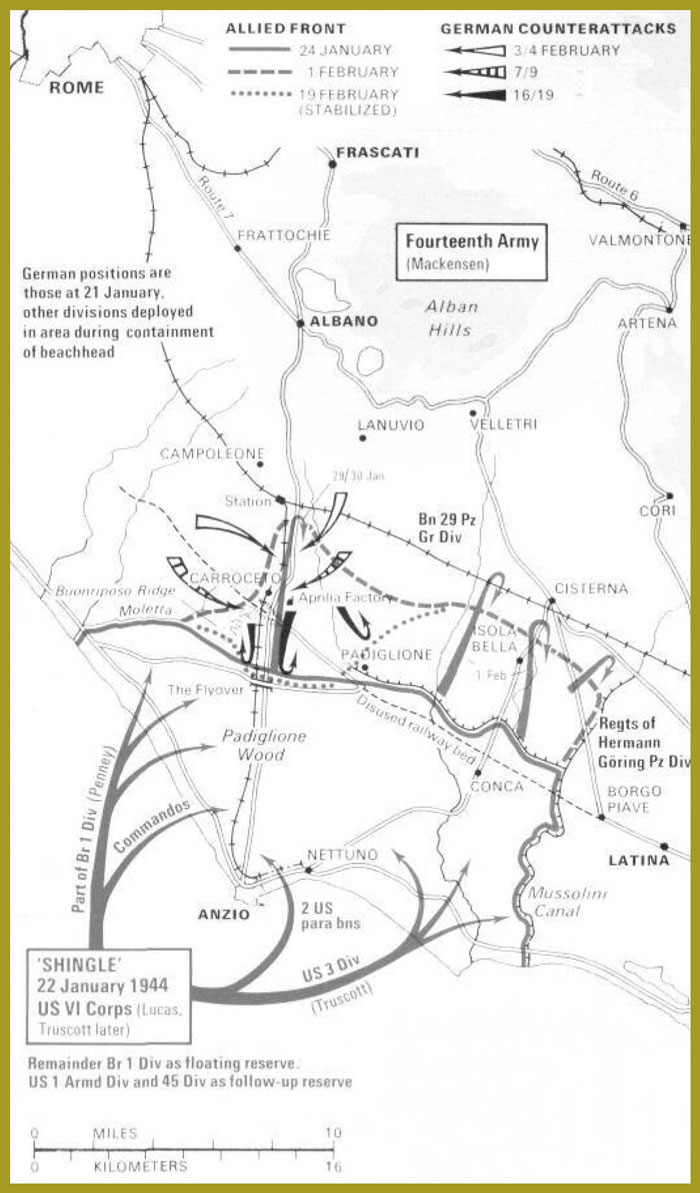

The Allied landings at Anzio on 22 January 1944 were designed to relieve pressure on Cassino, but the results were just the reverse: only the Allied success at Cassino allowed the US VI Corps to break out of its bungled position on the coast. Fifty thousand troops came ashore under Major General John Lucas, who made the fatal error of establishing a beachhead rather than pressing inland so as to wait for his heavy artillery and tanks. The Germans, under Mackensen, seized this welcome opportunity to pin down VI Corps at Anzio and mass forces for a major counterattack on 16 February. Not until the 19th was this halted, to be followed by a state of siege that would last until late May. Lucas was soon replaced by Major General Lucius Truscott, but it was too late to retrieve the situation.

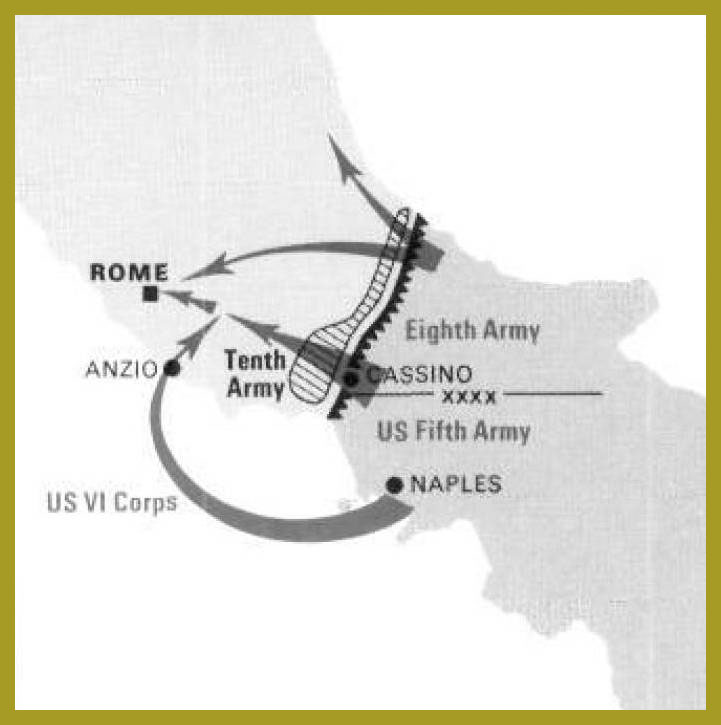

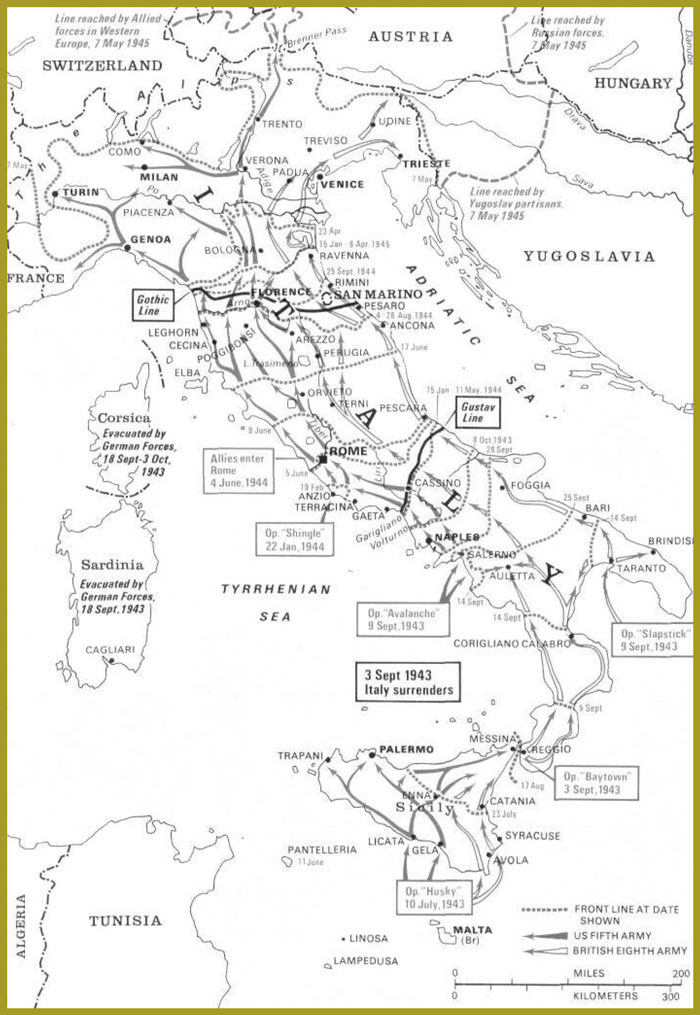

When the Allies finally broke the Gustav Line at Cassino, Clark's Fifth Army could resume its advance northward. Instead of swinging east in an effort to trap the German Tenth Army, Clark opted for capturing Rome - an important moral victory, though hardly necessary strategically. The Germans were able to delay his troops at Velletri and Valmontone long enough to ensure the escape of virtually all their forces in the area. The Allies finally entered Rome on 4 June 1944, just two days before the invasion of France.

The intention of the Anzio operation was to cut German communications by landing behind their front line.

The Allies on the road to Rome.

Mount Vesuvius' symbolic eruption failed to deter B-25 bombers of the US 12 th Air Force en route to Cassino.

A second pall of smoke hangs over the city and monastery as the bombs burst.

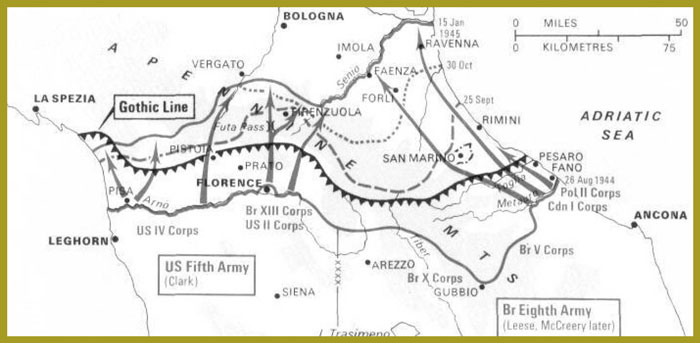

After Rome fell, the Allies forced the Germans back to their last defense - the Gothic Line. The Germans were now being reinforced from the Balkans and Germany, while Allied troops, aircraft and landing craft had been drawn off to France. British Eighth Army reached the Gothic Line on 30 August 1944 and attacked with considerable success, but the Germans held commanding positions on the Gemmano and Coriano Ridges that slowed the advance to Rimini until late September.

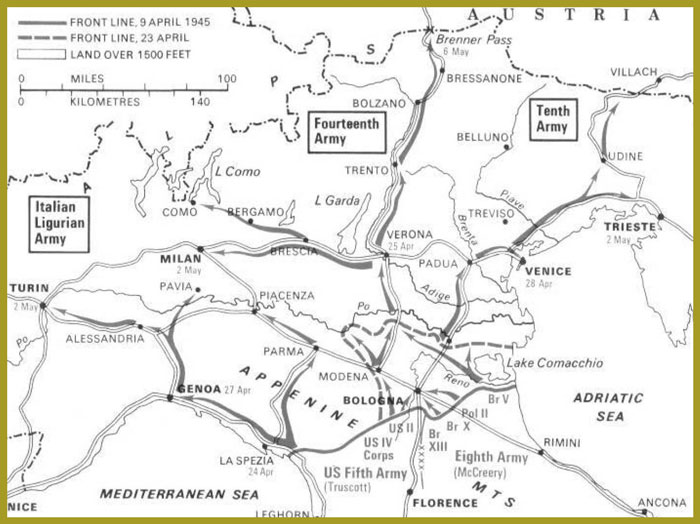

US Fifth Army had also broken through, but the approach of winter found Clark's exhausted forces short of their objective of Bologna. The Allied advance did not resume until April 1945, by which time Clark had become commander of 15 Army Group. Reinforcements and new equipment had reached him during the winter, and he planned a two-pronged offensive against Ferrara (Eighth Army) and Bologna (Fifth Army).

The German Tenth Army, now under General Herr, was surprised by the British attack across Lake Comocchio, which had been covered by a major artillery bombardment beginning on 9 April. The British moved into the Argenta Gap and Fifth Army, now led by Major General Lucius Truscott, broke through Lemelsen's German Fourteenth Army into the Po Valley (20 April). General von Vietinghoff, who had replaced Kesselring as overall commander in Italy, was forced back to the left bank of the Po, leaving behind all his heavy weapons and armor. The Fascist Ligurian Army had disappeared without a trace, and Axis forces in Italy were out of the fight when Bologna fell on 21 April. Vietinghoff signed the surrender of German forces in Italy on 29 April 1945.

The unsuccessful Anzio landing on 22 January 1944 which left both sides in a siege position.

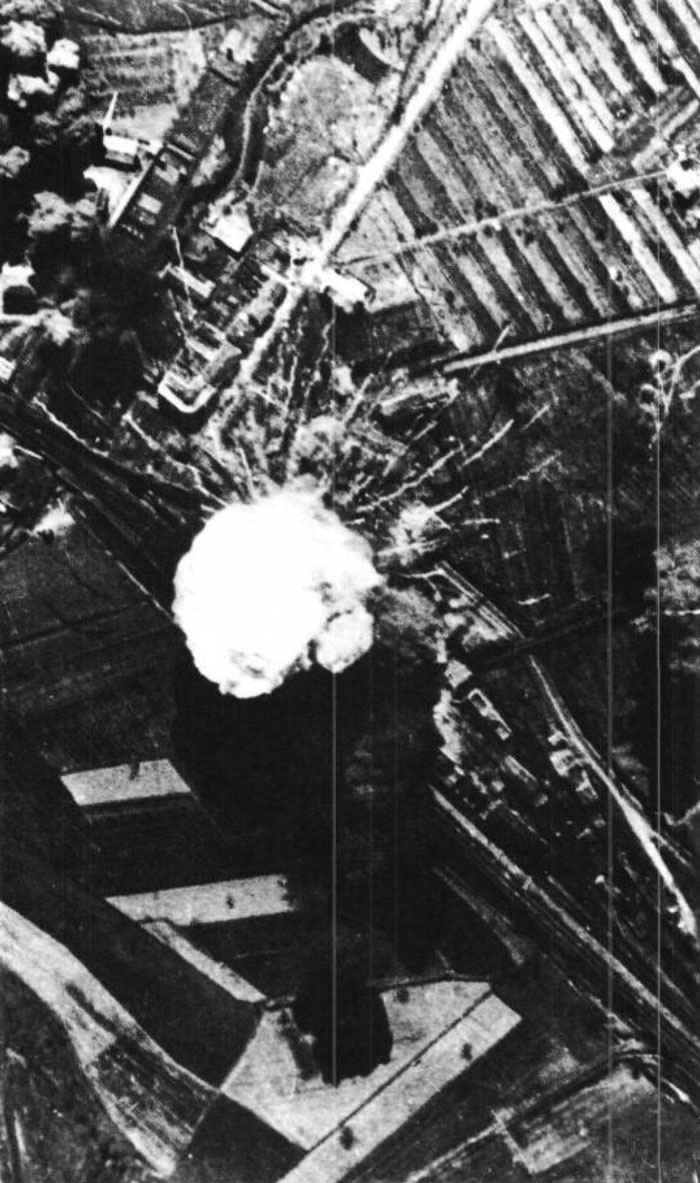

An Axis ammunition train receives a direct hit, March 1944.

Wehrmacht soldiers are marched into captivity north of Anzio.

Breaking the Gothic Line, the final German defense in Italy.

The Allies advance into Northern Italy.

US 105mm howitzers fire across the Arno, August 1944.

The final dive of a stricken Japanese bomber west of the Marianas Islands, June 1944.

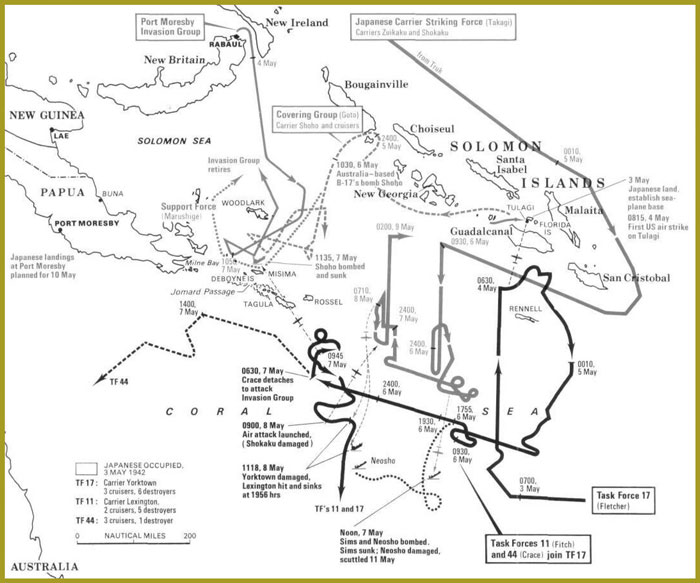

After the Doolittle bombing raid on Tokyo (18 April 1942), Japanese strategists sought ways to extend their defense perimeter in Greater East Asia. One of their options was to strike from Rabaul against Port Moresby, New Guinea; extend their hold on the Solomon Islands; and isolate Australia from the United States. This task was assigned to a five-part force designated MO, under command of Admiral Shigeyoshi Inouye. It comprised a Port Moresby Invasion Group of eleven transports and attendant destroyers; a smaller Tulagi Invasion Group charged with setting up a seaplane base on Tulagi in the southern Solomons; a Covering Group under Rear Admiral Goto that included the carrier Shoho; a smaller support group; and Vice Admiral Takagi's Carrier Striking Force, including Shokaku and Zuikaku. The operation's complexity suggests that no serious opposition was expected from the Allies, but Admiral Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet, moved quickly to counter it. A hastily improvised Task Force of three components, including the carriers Yorktown and Lexington, prepared to rendezvous in the Coral Sea on 4 May. The Japanese attack came one day earlier.

Tulagi was occupied without opposition, after which the opponents lost several days seeking one another in vain. Then Vice-Admiral Frank Fletcher dispatched British Rear-Admiral John Grace and his Task Force 44 to attack the Port Moresby Invasion Group (7 May). The Japanese mistook this group for the main Allied force and bombed it continuously until Grace made his escape by skillful maneuvering at the end of the day - not without inflicting some damage in return. Another Japanese error led to an attack on the tanker Neosho and the destroyer Sims at the same time that the main Allied force, still undetected, converged on Goto's Covering Group and sank Shoho.

The Japanese had already ordered the invasion transports to turn back, but now that Fletcher's position was known an air strike was launched against his group on the night of 7-8 May. Twenty-seven Japanese planes took off, of which only six returned. Then Shokaku was attacked and disabled; a reciprocal Japanese strike fatally damaged Lexington and put Yorktown out of action. At no time in the battle did opposing surface ships sight one another - a circumstance new to naval warfare, but soon to become familiar in the Pacific Theater.

Tactically, the Battle of the Coral Sea was a draw: the Japanese lost more planes, the US more ships. Strategically - and morally - it was a major US victory that came when one was needed most.

Midway was the turning point in the Pacific War and a watershed in modern history. Having failed to gain their objectives in the Coral Sea operations of early May 1942, the Japanese were determined to capture Midway as a base within striking distance of Hawaii. The destruction of the Pacific Fleet before US industry could build it up again was recognized as a matter of supreme urgency, besides which the occupation of Midway would eliminate the bombing threat to the home islands. The operation was scheduled for 4 June 1942.

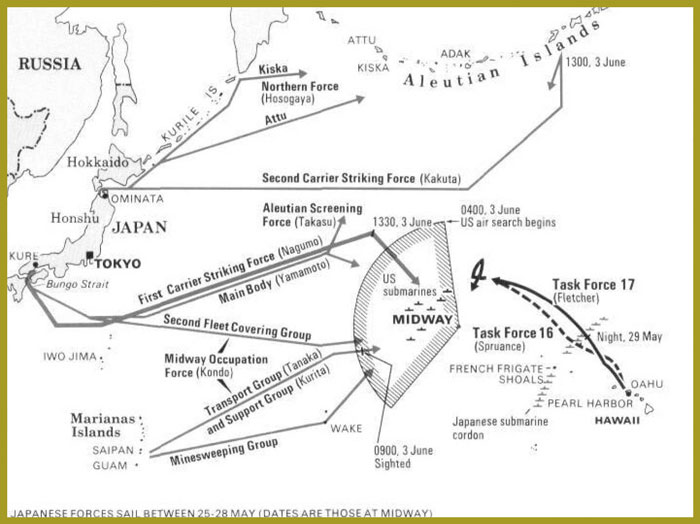

Fleet Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, formed a complex plan involving eight separate task forces, one of which was to make a diversionary attack on the Aleutian Islands. Almost all of the Japanese surface fleet would be involved - 162 warships and auxiliaries, including four fleet carriers and three light carriers commanded by Admiral Nagumo.

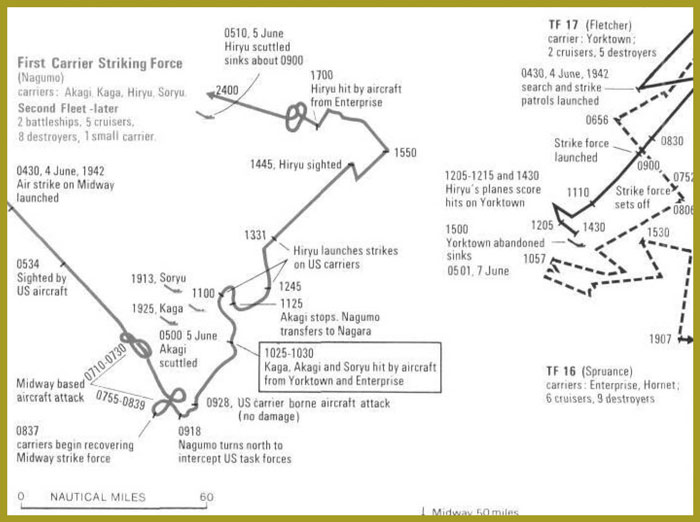

Information - and the lack of it - played a crucial role in the battle's outcome. Yamamoto believed that the carrier Yorktown had been destroyed in the Coral Sea along with Lexington. In fact, the damaged ship had been refitted for battle at Pearl Harbor in the incredibly short time of 48 hours. Nor did the Japanese realize that the Americans had broken their fleet code: Nimitz was fully aware of their plans. Although he had only 76 ships, three of them were fleet carriers - Yorktown, Enterprise and Hornet, with a total of 250 planes - whose presence was wholly unsuspected by the Japanese. As a result, Nagumo sent out few reconnaissance flights, which could have warned him of their presence.

Before dawn on 4 June, the Japanese dispatched 108 bombers to Midway, reserving 93 on deck armed for naval contingencies only with armor-piercing bombs and torpedoes. Many US planes were destroyed on the ground in the first attack, but those that survived took off to intercept the incoming bombers. They were largely destroyed by enemy Zeros, but they made a second strike imperative and thereby gave their carriers the chance to attack Nagumo's fleet while it was rearming with high-explosive and fragmentation bombs. When a Japanese reconnaissance plane finally reported detection of enemy carriers, Nagumo's planes were unready to mount a defense.

The first few US carrier strikes inflicted little damage, but the decisive blow caught all the newly armed Japanese planes on their flight decks waiting to take off. Five minutes later, three of the four Japanese carriers were sinking.

Hiryu escaped immediate destruction and disabled Yorktown, but damage inflicted on her by Enterprise was so severe that she had to be scuttled the following day. It was the end of Japanese naval supremacy in the Pacific.

Coral Sea was the first naval battle fought without surface vessels sighting each other.

The complex Japanese plan of attack at Midway involved no less than eight task forces.

The battle took place north of Midway and ended in decisive defeat for the Japanese.

Guadalcanal and the Solomon Islands

Prior to 1942, few Americans had ever heard of those far-flung islands whose names would become so familiar during the wary ears - names like Okinawa, Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal. Japanese forces waged a six-month battle for this island in the southern Solomons with US Marines who landed there on 7-8 August 1942. Their objective was a Japanese airbase still under construction to offset the loss of carrier air cover at Midway.

Admiral Fletcher, who had distinguished himself at Midway, was in overall command of operations in the southern Solomons. Rear Admiral R Kelly Turner led an amphibious task force responsible for landing the 19,000-man 1st Marine Division and its equipment. The Marines reached the airbase - renamed Henderson Field - soon after landing and found it deserted, but they came under heavy attack from the Japanese Navy, which dominated surrounding waters by night and soon sent reinforcements ashore to retake the island. The Marines strengthened the airfield's perimeter and used it to gain control of the sea lanes by day.

Two costly but inconclusive carrier battles were fought, one in August (Battle of the Eastern Solomons), the other in October (Battle of Santa Cruz), as the Japanese landed additional troops and supplies on Guadalcanal. On land, there were three major attacks on the Marine garrison, all of which were thrown back at considerable cost to the Japanese. Despite reinforcement, the Marines were exhausted by December, but the XIV Army Corps relieved them and the Japanese had to withdraw their own depleted forces.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com