RICHARD NATKIEL

ATLAS OF WORLD WAR II

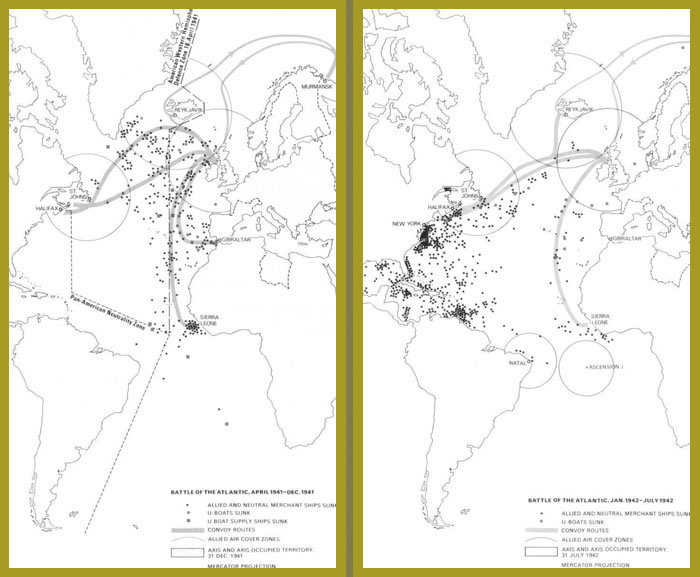

When the United States formally en tered the war at the end of 1941, the situation changed again. The US Navy was preoccupied with the Japanese threat in the Pacific, and the East Coast was left vulnerable to German submarine operations. For the first half of 1942, the US ships sailed without escorts, showed lights at night and communicated without codes - afflicted by the same peacetime mentality that had proved so disastrous at Pearl Harbor. Sparse anti-submarine patrols along the East Coast were easily evaded by the experienced Germans. It was months before an effective convoy system was established and extended as far south as the Caribbean. But by late summer of 1942 the US coastline was no longer a happy hunting ground, and the U-boats turned their attention back to the main North Atlantic routes.

The Battle of the Atlantic continues, with Allied air cover now apparent.

US troops disembark in Iceland. Air cover from Reykjavik drastically reduced U-boat strikes in the area from 1941 onwards.

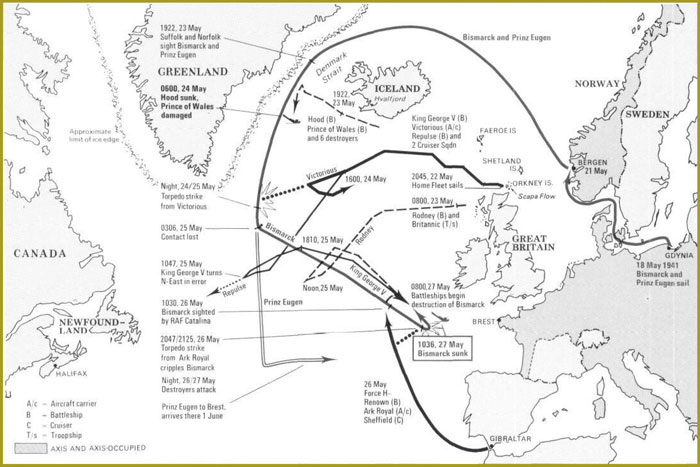

The formidable German battleship Bismarck was ready for action in the spring of 1941. Armed with 15-inch guns and protected by massive armor plate, she was an ocean raider to reckon with, accompanied on her first foray by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, which had finished her trials at the same time. On 18 May the two warships left Gdynia for Bergen, where RAF reconnaissance planes spotted them two days later. Their presence in Norwegian waters could only mean a foray into the Atlantic, and Royal Navy vessels in and around Britain were warned of the coming confrontation. Meanwhile, the German ships put to sea in foggy weather, bound for the Denmark Strait under command of Vice-Admiral Günther Lütjens. Not until late on 23 May were they spotted in the Strait by the cruisers Suffolk and Norfolk.

British Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland, commanding the Hood and the new battleship Prince of Wales, altered course to intercept the raiders. Prince of Wales still had workmen aboard and was by no means fully prepared to fight. Hood was a veteran, but she took a German shell in one of her aft magazines just as she closed with Bismarck and blew up. Only three crew members of 1500 survived. Bismarck then scored several direct hits on Prince of Wales, ending the engagement. Leaking fuel from a ruptured tank, Bismarck left the scene, shadowed by Prince of Wales and two cruisers. Prinz Eugen broke away and returned to Brest, and the Royal Navy lost contact with the damaged German battleship. On 26 May she was spotted by an RAF Catalina north of Gibraltar.

Force H, heading northeast from Gibraltar, included the carrier Ark Royal, which launched her Swordfish against the disabled Bismarck. A torpedo strike jammed Bismarck's rudder and left her an easy prey to the battleships Rodney and King George V, which arrived that night (26-27 May) to pour heavy-caliber shells into the German warship. A torpedo from the cruiser Dorsetshire completed the Bismarck's destruction. She sank with all but 110 men of her crew, which numbered 2300.

Charting the Bismarck's course to destruction, May 1941.

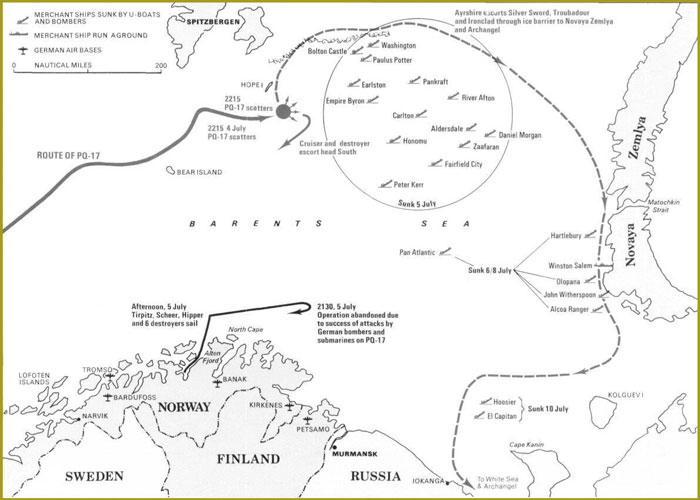

The loss of Allied convoy PQ-17 in July 1942 proved a grievous blow to morale. Almost two-thirds of the ships involved failed to reach their destination, Archangel, and thousands of tons of urgently needed materiel were lost.

Hazardous duty fell to the men who convoyed supplies to Russia after the German invasion of June 1941. The forces of nature on the arctic run posed a threat equal to that of the Germans. Savage storms and shifting ice packs were a constant menace. In the summer months, the pack ice retreated north, and convoys could give a wider berth to enemy airfields on the Norwegian and Finnish coasts, but the long summer daylight made them vulnerable to U-boats. When the ice edge moved south again, the U-boat threat lessened with the hours of daylight, but it was more difficult to stand clear of the airfields.

Many Allied seamen lost their lives on the arctic run, including most of the members of PQ-17, which sailed for Russia on 27 June 1942. Thirty-six merchant ships were heavily escorted by Allied destroyers, battleships, submarines, a carrier and various smaller craft. Near Bear Island in the Barents Sea, the convoy lost its shadowing aircraft in heavy fog. At the same time, word came that German surface ships Tirpitz, Scheer and Hipper had left their southern bases.

Early on 4 July, German planes torpedoed a merchantman and sank two ships of the convoy. The German ships arrived at Altenfjord, Norway, and operations control in London expected an imminent sailing to intercept the convoy, whose distant cover had been withdrawn per previous plans. Sir Dudley Pound, First Sea Lord, saw a chance for the convoy's ships to evade the German raiders by scattering; orders to this effect were issued on 4 July. The long-range escort, except for the submarines, left the convoy to rendezvous with the close cover, leaving PQ-17 scattered and defenseless. German U-boats and aircraft began to pick off the hapless ships, and the surface-ship mission that set sail from Altenfjord on 5 July was canceled as unnecessary late that day.

Between 5 and 8 July, almost two- thirds of the convoy was sunk in icy waters hundreds of miles from its destination of Archangel. The armed trawler Ayrshire succeeded in leading three merchantmen up into the ice, where they camouflaged themselves with white paint and rode out the crisis. These three were among the eleven merchant ships that finally reached Russia with desperately needed supplies. The other 25 went down with their crews and thousands of tons of materiel destined for the Soviet war effort.

The Sea Roads Secured, 1943-45

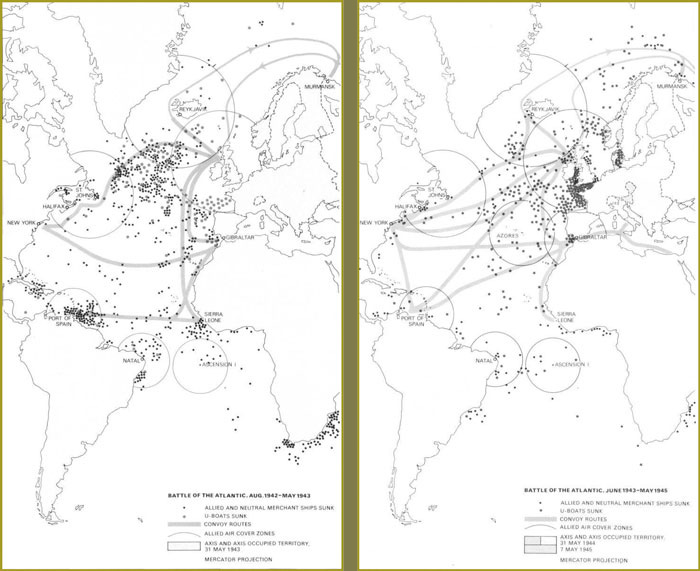

By mid 1942 the Battle of the Atlantic had shifted away from the US East Coast to more distant areas, where German U-boats continued to make successful raids on Allied shipping. Many oil tankers and other vessels were lost south of the Caribbean, off the Brazilian coast and around the Cape of Good Hope. Before the year was out, the Allies had augmented the convoy system by specially trained Support Groups - escort vessels that would help endangered convoys or seek out U-boats in areas where they had been detected. These groups usually included a small aircraft carrier and an escort carrier; along with surface forces. They were free of normal escort duties and could therefore hunt the U-boats to destruction.

Continuation and (below right) conclusion of the Battle of the Atlantic.

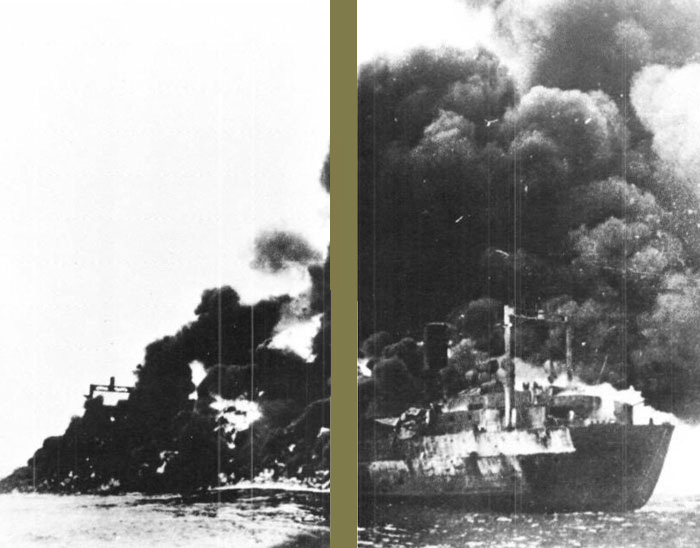

A U-boat victim burns in mid- Atlantic. By the summer of 1943 the worst Allied shipping losses were over.

A cryptographic breakthrough at the end of 1942 increased Allied intelligence on German deployments, and changes in the code system (June 1943) made it more difficult for the Germans to anticipate Allied movements. Even so, late 1942 and early 1943 brought great difficulties. Allied commitments were increased by the invasion of North Africa, which drew off North Atlantic escort forces, with corresponding shipping losses. In March 1943, the climax of the Battle of the Atlantic, 120 Allied ships were sunk. Then the support groups returned from North African waters, and the US industrial effort paid dividends in accelerated production of escort carriers and other needed equipment. Improvements in radar and long-range scout planes, years in the making, came to the fore, and Allied crews began to capitalize on their hard-won experience. In April 1943, shipping losses declined, and the following month 41 U-boats were destroyed. On 22 May the German submarines were ordered to withdraw from the North Atlantic.

After the summer of 1943, the U-boats were never again the threat that they had been. The 'wolf-pack' tactic was abandoned in 1944, and the remaining submarines prowled singly in an area increasingly focused around the British Isles. At the war's end, fewer than 200 were still operational. Allied victory in the Atlantic was largely a function of superior co-ordination of effort, which ultimately offset the initial German advantage in submarine technology.

The German retreat from El Alamein, November 1942.

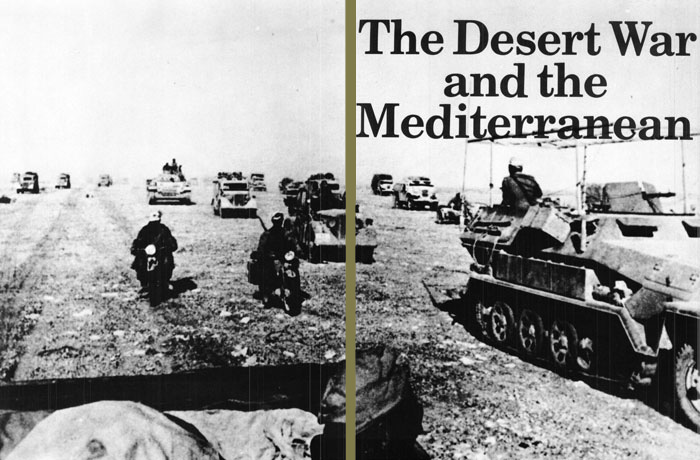

The Desert War and the Mediterranean

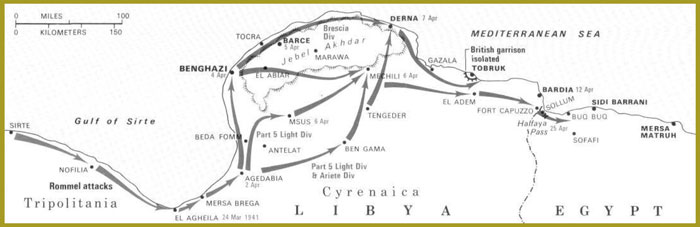

The first German troops began landing in North Africa on February 1941, under command of General Erwin Rommel, who would earn the nickname 'Desert Fox.' His leadership abilities were acknowledged by comrades and enemies alike. Rommel soon saw that British forces in Africa were weak, and that no reinforcements would be forthcoming. On 24 March German forces took El Agheila easily, and the 5 Light Division went on to attack the British 2 Armored Division at Mersa Brega. There they encountered stiff resistance, but the British failed to counterattack and lost their advantage.

Instead of choosing among three alternative courses of attack, Rommel moved boldly on all three fronts: north to Benghazi, northeast to Msus and Mechili and east to Tengeder, to threaten British supply lines. Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, in overall command of British forces, lacked the men to counter this multiple attack, launched on 5 April. His single armored division fell back and was reduced to a remnant by mechanical failure. The defense at Mechili, 3 Indian Brigade, was soon overwhelmed, with what remained of the 2 Armored Division. The 8 Australian Division retreated from Benghazi to Derna, thence toward Tobruk, which was being reinforced with the 7 Australian Division.

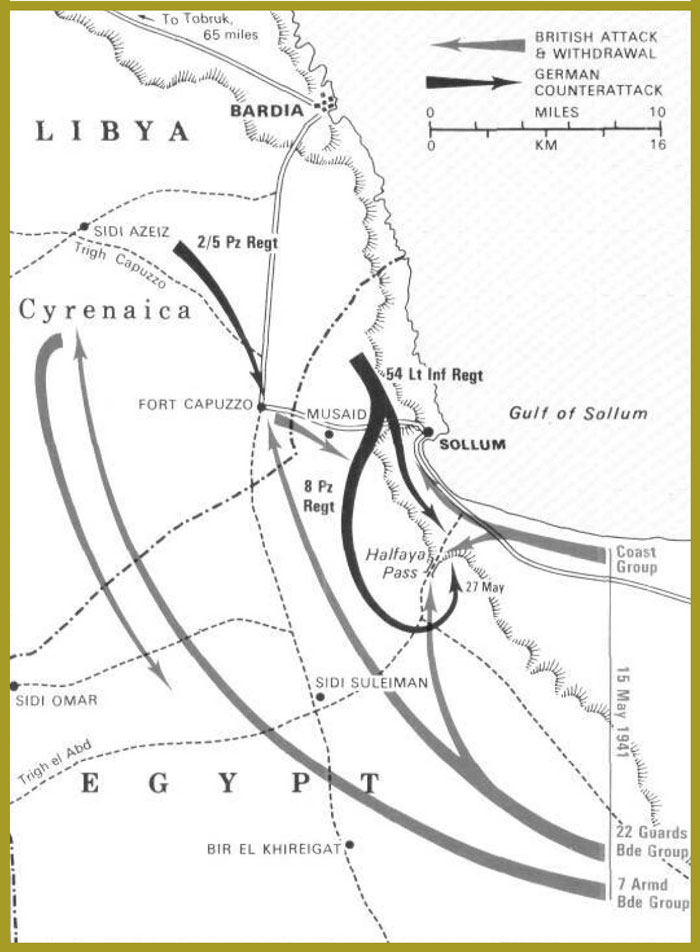

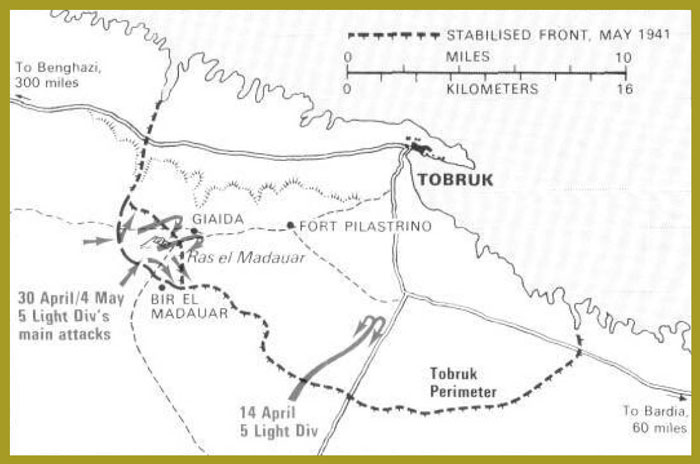

On 14 April the German 5 Light Division penetrated the Tobruk perimeter a short distance, but was driven back. Italian troops were now coming up to replace the German units making ready to cross the Egyptian frontier. The British garrison at Tobruk was isolated in the midst of Axis forces, and on 25 April the Germans broke through the Halfaya Pass into Egypt. Rommel was dissatisfied with the failure to capture Tobruk, and another full-scale attack struck the British there on 30 April. Axis troops pushed a salient into the western sector, but it was contained after four days of fighting.

The Germans press eastwards through Libya into Egypt.

Rommel enters Egypt.

Rommel and his officers inspect a captured British tank.

The Allies isolated at Tobruk.

Rommel directs operations.

Rommel's German units, the Deutsches Afrika Korps (DAK), and their allies suffered a setback in the Crusader Battles with the British Eighth Army late in 1941. Tobruk was relieved, and Rommel had to pull back to El Agheila, having suffered 38,000 Axis casualties as against 18,000 for the British. His men were exhausted, supplies were running out and 300 German tanks had been destroyed in the Libyan desert.

British forces pursued Rommel to El Agheila, believing that his shattered units would be unable to react. However, successful airraids on Malta had restored the German supply line across the Mediterranean, and Rommel's forces were quickly rebuilt to fighting strength. On 21 January 1942 they made an unexpected advance that pushed Eighth Army back toward Agedabia. In a matter of days the British faced encirclement at Benghazi and were forced to retreat to the defensive position at Gazala. The line there consisted of minefields running south to Bir Hacheim and a series of fortified keeps that were manned by XIII Corps brigades.

DAK forces under Cruewell swung around Bir Hacheim on 26 May to outflank the Gazala Line, but they were attacked from both sides on Sidra Ridge and stopped short with loss of a third of their armor. Their water and fuel were running out, and Rommel tried to push a supply line through the British minefields without success. He then moved all his remaining armor into 'the Cauldron' to await the impending British counterattack.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com