RICHARD NATKIEL

ATLAS OF WORLD WAR II

France and Britain tried to forestall the Nazi assault on Poland by issuing a joint guarantee to the threatened nation. This was supposed to provide leverage whereby the democracies could persuade the Poles to make concessions similar to those made by the Czechs. But Hitler's aggressiveness grew more apparent throughout the spring and summer of 1939. In April he revoked both the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935. Then he sent emissaries to the Soviet Union, where Joachim von Ribbentrop concluded both an economic agreement and a Non- Aggression Pact with Josef Stalin. By 1 September 1939, the Germans were ready to invade Poland on two fronts in their first demonstration of blitzkrieg - lightning war - a strategy that combined surprise, speed and terror. It took German forces just 18 days to conquer Poland, which had no chance to complete its mobilization. The Poles had a bare dozen cavalry brigades and a few light tanks to send against nine armored divisions. A total of five German armies took part in the assault, and German superiority in artillery and infantry was at least three to one. The Polish Air Force was almost entirely destroyed on the ground by the Luftwaffe offensive supporting Army Groups North and South.

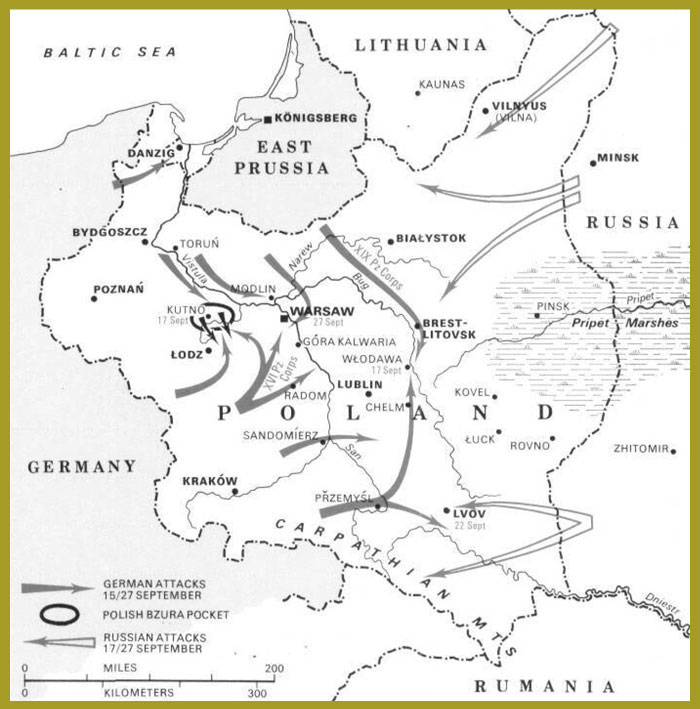

The Nazi thrust into Poland, early September.

German troops enter Warsaw. The city finally surrendered on 27 September after 56 hours of resistance against air and artillery attack.

Thinly spread Polish troops staggered back from their border, and German forces were approaching Warsaw a week later. The Poles made a last-ditch effort along the Bzura River to halt the German advance against their capital, but they could not withstand the forces pitted against them. The Polish Government fled to Rumania, and on 27 September Warsaw finally capitulated.

Russia counterattacks, mid to late September.

Meanwhile, Britain and France had declared war on Germany 48 hours after the invasion of Poland. Australia, New Zealand and South Africa soon joined them. Since the Western Allies had failed in their diplomatic efforts to enlist Soviet support, they faced a united totalitarian front of Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia (which could be counted upon to take full advantage of Poland's impotence). Stalin had made it clear that he wanted a free hand in Eastern Europe when he cast his lot with Germany. Before the month of September was out, it became obvious that Russia and Germany had reached a secret agreement on the partition of Poland during the summer months. On 17 September Soviet troops crossed the eastern frontier to take Vilnyas; a German-Soviet Treaty of Friendship was announced two days later. On 28 September, after Warsaw's surrender, Russia annexed 77,000 square miles of eastern Poland. The other 73,000 square miles, bordering on Germany, were declared a Reich protectorate.

Hitler counted on Allied reluctance to assume an active role in the war, and he was not disappointed. The six-month hiatus known as the Phony War lasted from September 1939 until April 1940, when Germany invaded Norway and Denmark. In the interim, Britain and France made plans that could only fail, because they were based on a negative concept: avoidance of the costly direct attacks that had characterized World War I. New Anglo-French strategy focused on naval blockade and encirclement - indirect methods that were no match for the new blitzkrieg tactics of Nazi Germany.

The partition of Poland as agreed by Germany and Russia.

Early in 1940 Hitler turned his attention to Scandinavia, where he had a vested interest in Swedish iron ore imports that reached Germany via the Norwegian port of Narvik. Norway had a small Nazi Party, headed by Vidkun Quisling, that could be counted upon for fifth-column support. February brought evidence that the Allies would resist a German incursion into Norway when the Altmark, carrying British prisoners, was boarded in Norwegian waters by a British party. Both sides began to make plans for a Northern confrontation.

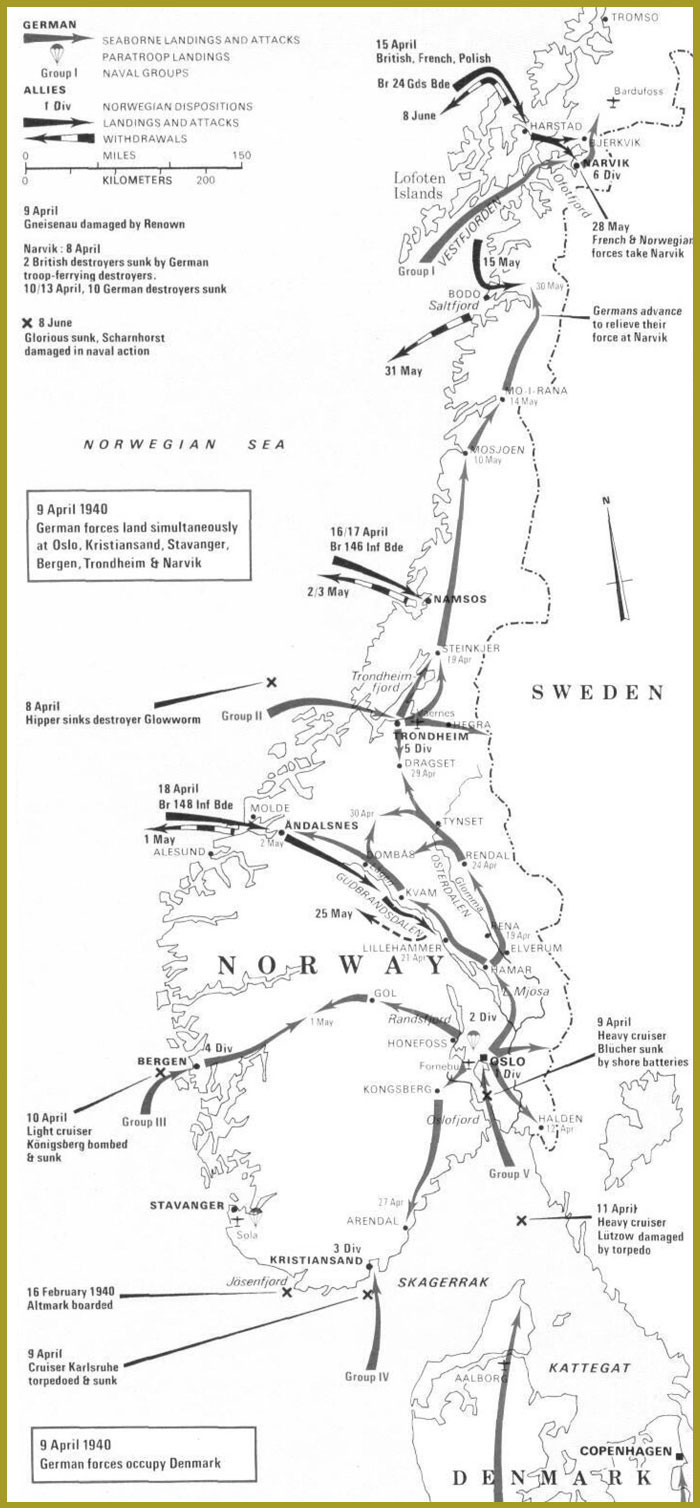

The Reich expands to the north and east.

On 9 April the Germans launched their invasion of Norway and Denmark, based on a bold strategy that called for naval landings at six points in Norway, supported by waves of paratroops. The naval escort for the Narvik landing suffered heavy losses, and the defenders of Oslc sank the cruiser Blücher and damaged the pocket battleship Lützow. Even so the Germans seized vital airfields, which allowed them to reinforce their assault units and deploy their war planes against the Royal Navy ships along the coast Denmark had already been overrun and posed no threat to German designs.

German forces forge through Denmark and make six simultaneous landings in Norway.

Norwegian defense forces were weak, and the Germans captured numerous arms depots at the outset, leaving hastily mobilized reservists without any weapons. Allied planning proved wholly inadequate to German professionalism and air superiority. Kristiansand, Stavanger, Bergen, Trondheim and Narvik were all lost to the Germans, along with the country's capital, Oslo. Few Allied troops were trained for landing, and those who did get ashore were poorly supplied.

In May, British, French and Polish forces attempted to recapture two important cities, but their brief success at Narvik was offset by the bungled effort at Trondheim to the south. Troops in that area had to be evacuated within two weeks, and soon after Narvik was abandoned to the Germans when events in France drew off Allied troops.

Norway and Denmark would remain under German occupation throughout the war, and it seemed that Hitler's Scandinavian triumph was complete. However, German naval losses there would hamper plans for the invasion of Britain, and the occupation would tie up numerous German troops for the duration. The Allies were not much consoled by these reflections at the time. The Northern blitzkrieg had been a heavy blow to their morale, and the Germans had gained valuable Atlantic bases for subsequent operations.

A Norwegian port burns as the Germans follow through their surprise attack.

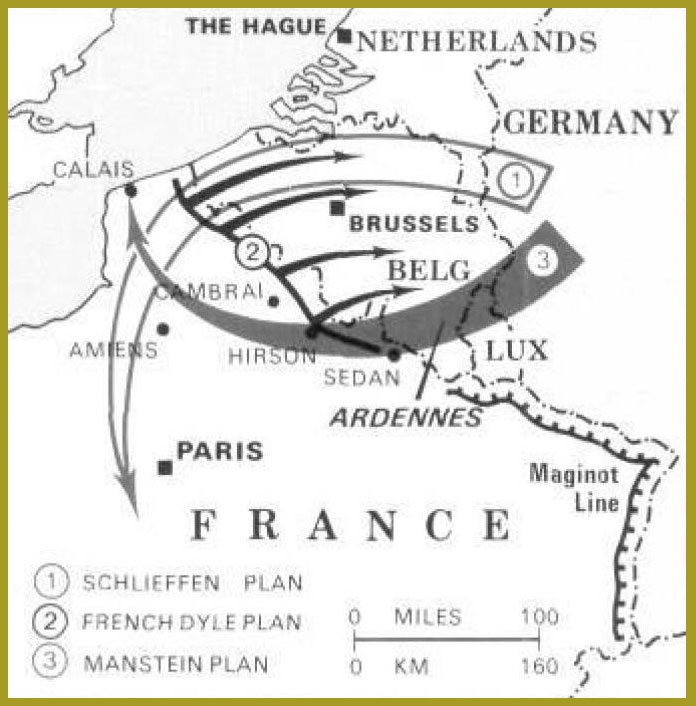

On the Western Front, both Allied and German armies scarcely stirred for six months after the declaration of war. The Allies had an ill-founded faith in their Maginot Line - still incomplete - which stretched only to the Belgian border. The threat of a German attack through Belgium, comparable to the Schlieffen Plan of 1914, was to be met through the Dyle Plan. This strategy called for blocking any advance between the Ardennes and Calais by a swift deployment of troops into Belgium from the vicinity of Sedan.

German General Erich von Manstein anticipated this plan, whose weak link was the hilly Ardennes region - widely believed to be impassable to an advancing army. Manstein prepared for an attack on the Low Countries to draw the Allies forward, followed by a swift surprise breakthrough in the Ardennes that would aim for Calais. This would cut off any Allied troops that had moved into Belgium to implement the Dyle Plan.

Thrust and counterthrust at the Belgian border.

The Allies, discounting the possibility of a large-scale German advance through the Ardennes, garrisoned the Maginot Line and deployed their remaining forces along the Franco-Belgian border. There troops stood ready to advance to the River Dyle should the Belgians need assistance. Experienced French and British units were designated for this advance, which left the sector opposite the Ardennes as the most vulnerable part of the Allied line.

German soldiers fire at attacking aircraft from the remains of a demolished bridge, Holland, 1940.

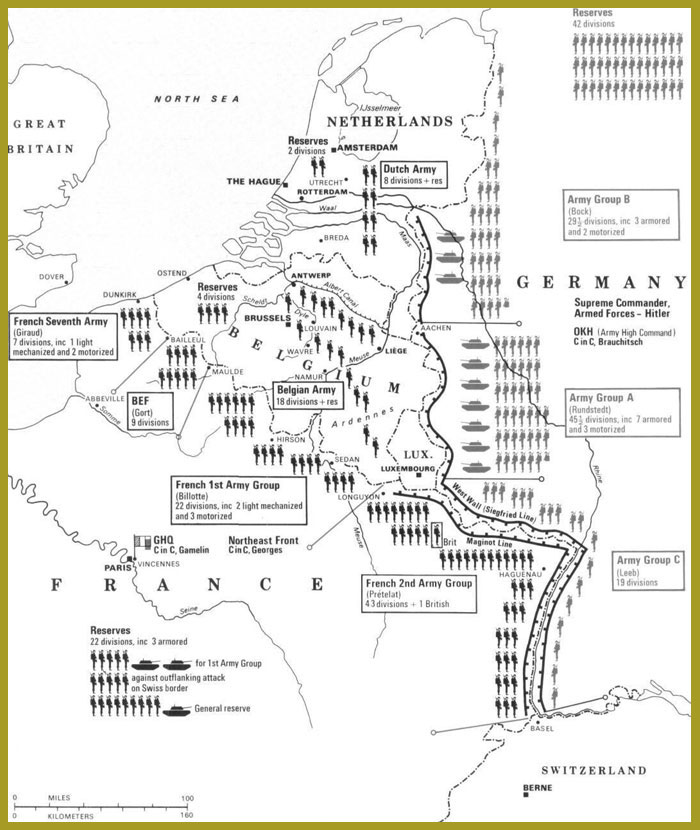

On paper, the opposing forces were almost equally matched. The Allies had a total of 149 divisions as against 136 German divisions, with some 3000 armored vehicles to the Germans' 2700. But the Germans had several advantages, not the least of which was superiority in the air - some 6000 fighters and bombers to the Allies' 3300. Less tangible, but no less important, was their innovative and flexible approach to modern warfare. The Allies still clung to outmoded ideas of positional warfare, and wasted their armor in scattered deployments among their infantry divisions. The Germans massed their armor in powerful Panzer groups that could cut a swath through the most determined resistance. Where necessary, dive-bombing Stukas could support German tanks that had outstripped their artillery support in the field. It was a lethal combination.

In organization, too, the Allies lagged far behind the German war machine. Their training, communications and leadership were not comparable to those of Hitler's army, which was characterized by dynamic co-ordination of every detail. General Maurice Gamelin, Allied Commander in Chief, now in his late sixties, was in far from vigorous health. Considerable friction developed between the British and French commands. The Allies also counted too much upon cooperation from the Belgians and the Dutch, who were slow to commit themselves for fear of provoking a German attack. German leadership, by contrast, was unified and aggressive - provided Hitler did not take a direct hand in military affairs.

The forces of the Reich mass at the Siegfried Line.

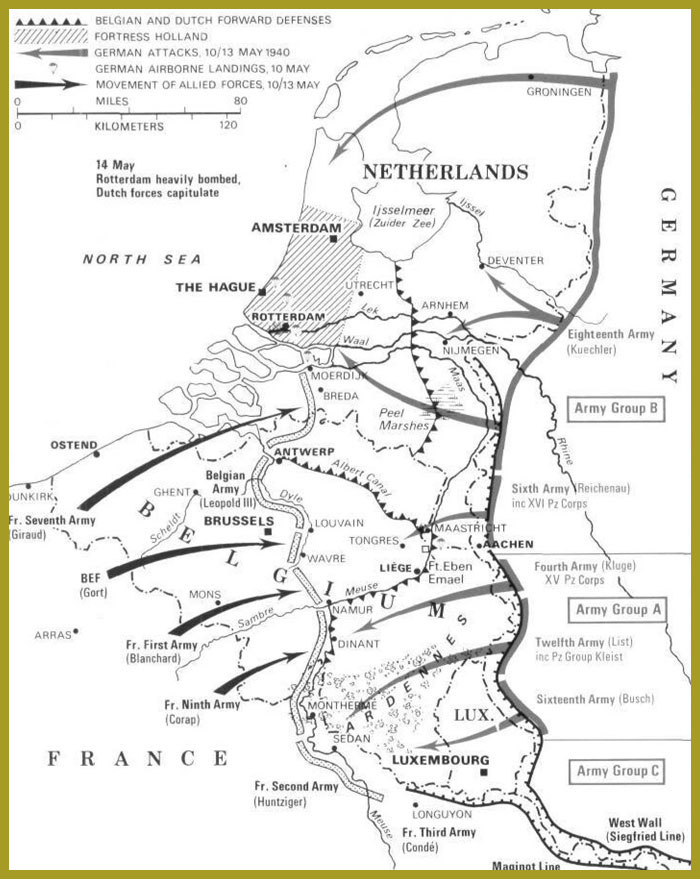

The German assault on the West was launched on 10 May 1940, when aerial bombardments and para- troop landings rained down on the Low Countries at daylight. Dutch airfields and bridges were captured, and German troops poured into Holland and Belgium. Both countries called for help from France and Britain, as the Dutch retreated from their borders, flooding their lands and demolishing strategic objectives in an attempt to halt the invasion. Their demoralization was completed by a savage air attack on Rotterdam (14 May), after which Dutch forces surrendered. Queen Wilhelmina and her government were evacuated to England.

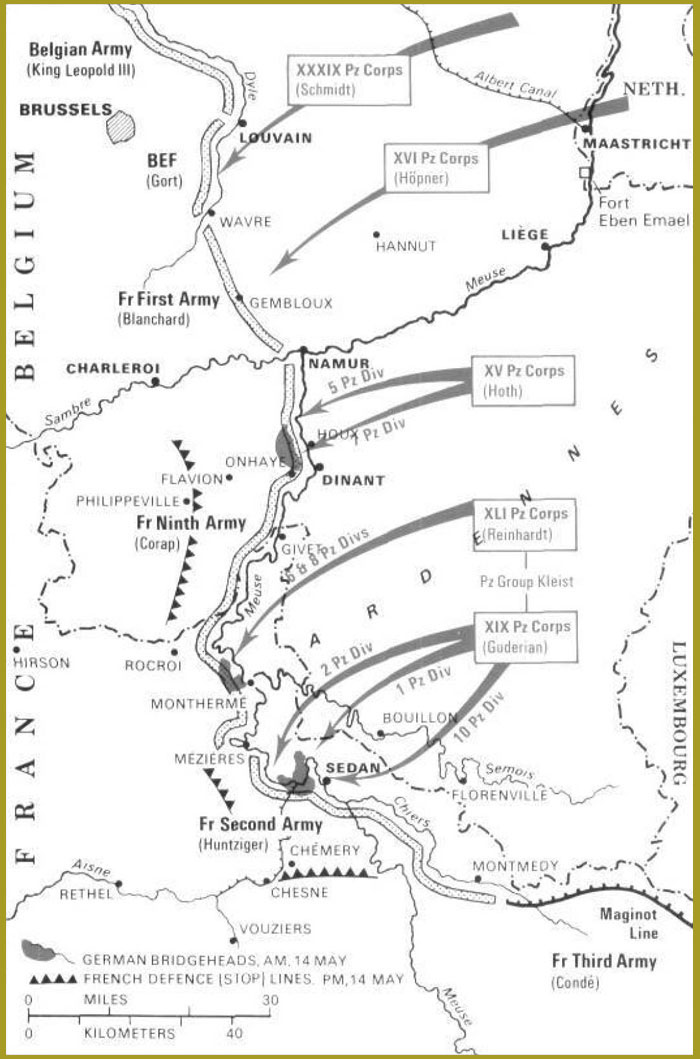

The French Seventh Army had tried to intervene in Holland, but it was repulsed. In Belgium, the German capture of Eben Emael, a key fortress, and the accomplishment of Manstein's plan to traverse the Ardennes with his Panzer divisions, gave access to the Meuse. Three bridgeheads were secured by 14 May, and the Allied line had been breached from Sedan to Dinant. The Panzer divisions then made for the sea, forcing back the British Expeditionary Force and two French armies in Belgium. Allied forces were split, and their attempt to link up near Arras (21 May) was a failure. German tanks had already reached the sea at Noyelles and were turning north toward the Channel ports.

German forces pour into the Low Countries.

Only the unwarranted caution of German commanders prevented wholesale destruction of Allied forces in Belgium. On 23 May orders to halt came down from Hitler and Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt. The German advance did not resume until 26 May, and the beleaguered Allies were able to fall back around Dunkirk.

Motorized Dutch soldiers are pictured traversing a dyke.

Dunkirk and the Fall of France

A determined defense at Calais, and German failure to capitalize on the chance of seizing the Channel ports, enabled the Royal Navy to begin evacuating British troops from Dunkirk. Between 27 May, when Allied resistance at Calais ended, and 4 June, 338,226 men of the British Expeditionary Force left Dunkirk along with 120,000 French soldiers. The Germans tried to prevent the rescue operation with attacks by the Luftwaffe, but the Royal Air Force distinguished itself in safeguarding the exodus. With the loss of only 29 planes, RAF pilots accounted for 179 German aircraft in the four-day period beginning 27 May. Royal Navy losses totaled six destroyers sunk and 19 badly damaged, plus many smaller craft. The toll in lives and materiel would have been much higher had chance not favored the Allies in the form of Germany's inexplicable pause at Noyelles.

The Panzer thrust to the Meuse.

To the south, General Maxime Weygand tried to rally remaining French forces for defense of the Somme Line. The Germans began to attack south on 5 June, and the line gave way despite courageous fighting by many French units. By 10 June the Germans had crossed the Seine, and Mussolini took advantage of the situation by declaring war on France. Italian troops moved in and encountered stiff resistance, but overall French morale and confidence were at a low ebb. The government removed to Bordeaux and rejected Prime Minister Winston Churchill's offer of a union between Britain and France. By 16 June Premier Reynaud was resigning in favor of Marshal Henri Petain, who announced the next day that France was seeking an armistice.

Germany expands westwards to the Channel coast.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com