THE WAR IN CAMBODIA 1970-75

The Marine Royale Khmere was established in 1954 to provide limited patrolling of the coast and major waterways of Cambodia. The riverine headquarters was established at Chrui Chhang War Naval Base across the Mekong from Phnom Penh; a coastal base was built at Kompong Som. Ex-French and US ships composed the bulk of its small fleet until 1964; thereafter, limited deliveries of Chinese and Eastern Bloc river and sea craft entered the MRK inventory. The Cambodians also seized a number of US riverine craft which strayed into Khmer territory, including two airboats captured from the US Army Special Forces in 1968. A Marine Corps of four Bataillons de Fusiliers-Mar ins (BFM) was maintained for static defence.

After the 1970 change of government, the rechristened Marine Nationale Khmere took on a more important role as it escorted supply convoys up the Mekong and provided logistical support for the FANK. Assisting the MNK in its new responsibilities, the South Vietnamese Navy lent extensive convoy protection and helped patrol the coastline against enemy infiltration.

By 1972 the MNK had gained enough experience to assume responsibility for convoy support operations. The KAF contributed to the effectiveness of these operations with AC-47 cover, while the South Vietnamese Air Force lent helicopter gunships to overfly convoys along the Lower Mekong. The MNK riverine forces also coordinated operations on the Tonle Sap in conjunction with the FANK Lake Brigade. Along the coast, the MNK continued to rely heavily on the South Vietnamese Navy to assist with coastal surveillance. Patrolling at sea became more important after South Vietnamese patrols reported in April the first attempt by a North Vietnemese vessel to infiltrate into Cambodia. The vessel was sunk, with heavy secondaries.

MNK Monitors, converted landing craft armed with 105mm guns, assemble at Chrui Chhang War Naval Base outside Phnom Penh.

The MNK was challenged in early 1972 by an increase in enemy activity against Mekong shipping. After one merchant vessel was destroyed and three others damaged at the Chrui Chhang War Naval Base the MNK formed a Harbour Defence Unit. MNK defenders were further bolstered by the naval infantry, who were used for active riverbank patrolling.

Both MNK performance and enemy activity increased during the following year. In January 1973 Communist frogmen attacked merchant vessels on the Mekong; several ships were destroyed at the cost of three enemy swimmers. During the same month an enemy infiltration route was identified from Kompong Som Bay to inland supply bases. Countering these threats, the MNK maintained high morale - mainly due to sufficient rice rations, good leadership, and prompt payment of wages; and because the MNK was not highly dependent on US air power, it was not adversely affected when this support was terminated in August.

The MNK increased its efforts along the Mekong corridor in mid-1973 as the FANK began placing a higher reliance on the navy for logistical support and casualty evacuation. To handle these responsibilities the MNK increased its strength to over 13,000 men by December 1973. This included an expansion of the Marine Corps, growing from four battalions in August to nine BFMs in December. Elements of the Marines were used extensively in ground operations, including the heavy fighting at Kompong Cham in September. In addition to BFM support, the MNK ran 20 convoys between Phnom Penh and Kompong Cham under the operational order 'Castor 21' and conducted an amphibious assault by the FANK 80th Brigade into the Communist-held half of the city.

In 1974 MNK performance remained impressive. The MNK commander, Commodore Vong Sarendy, deserved much of the credit for maintaining high discipline and morale among his sailors. During that year Sarendy supervised the second major MNK amphibious operation in March when Operation 'Castor 50' delivered 30 M113 APCs, four 105mm howitzers, six trucks, and 2,740 troops to the battlefield at Oudong.

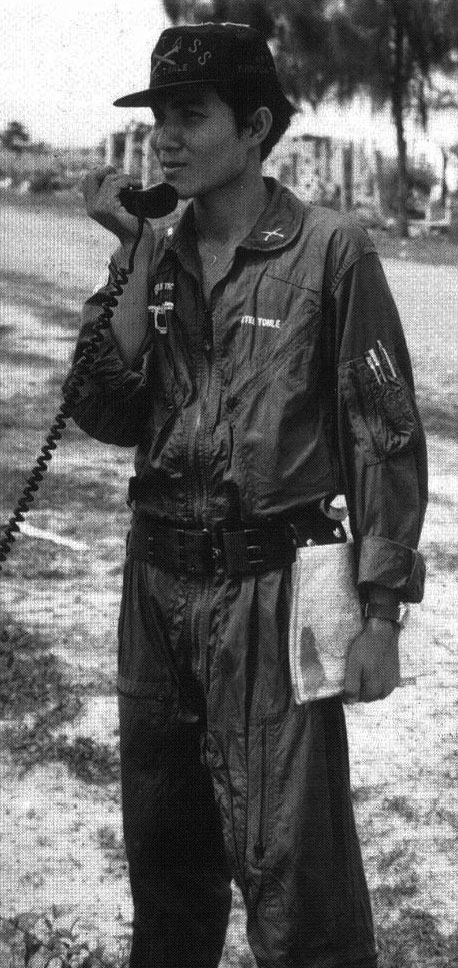

A FANK forward air guide talks on an AN/PRC-25 radio. He wears an olive US flightsuit, and a black baseball cap from the USAF 23rd Tactical Air Support Squadron, the unit providing OV-10 forward air control coverage over Cambodia.

MNK strength peaked in September 1974 at 16,500 men. One-third of the total force was assigned to the Marines, whose organisation was starting to suffer from poor morale. Initially intended for static defence, the BFMs were used as intervention forces on offensive operations; ten BFMs were being used in this role in September, with the 11 BFM in training. Yet the Marines were denied hazardous duty pay comparable to that paid by the FANK, and desertions increased. The problem was never rectified.

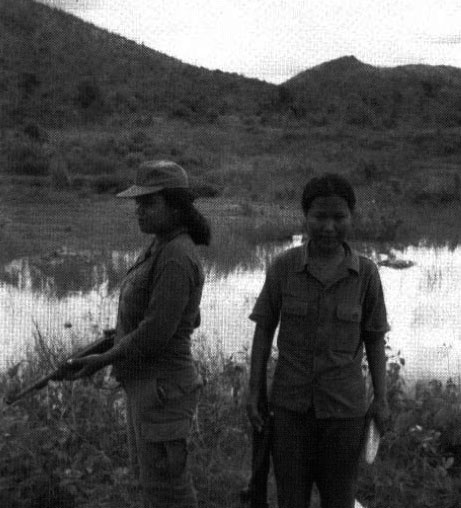

Many women answered the FANK recruiting drives; and many, like these two, were incorporated into village militia units lightly armed with Mi carbines. Olive fatigues, khaki cap.

As the 1974-1975 dry season opened, the effectiveness of the MNK was immediately curtailed by heavy enemy mining of the Mekong. Without proper minesweeping equipment the MNK remained unable to open the Mekong corridor. During the final weeks of the war the MNK riverine forces around the capital were rendered useless. Along the coast, MNK vessels lost no time in evacuating refugees to safety; as late as 9 May, three ships arrived in the Philippines with 750 passengers.

Like the rest of the Royal Armed Forces, the Royal Khmere Navy wore a white dress uniform. On other occasions a light grey work uniform was used with a matching peaked cap. Both of these uniform combinations were maintained in the MNK. A wreathed gold anchor embroidered on black was worn on the MNK peaked cap. Naval infantry wore the same fatigue uniform as the FANK. Shoulder boards in the Marine Royale Khmere were identical to those of the FARK, with the addition of a fouled anchor on the inner end.

During the Republic the MNK standardised the black shoulder boards or shoulder loops used in the FANK.

The MNK had several unit and qualification insignia, the former worn on the left shoulder and the latter on the right chest. An MNK pocket badge in normal and subdued forms was worn on the left breast. All BFM wore the same shoulder insignia, consisting of crossed rifles on a shield patterned after the Republican flag.

The armed Communist struggle against the Cambodian government began with the ill-fated April 1967 rebellion in Battambang Province. Although the revolt was quickly suppressed the Communists, called the Khmer Rouge by Prince Sihanouk, began to expand their insurgency. Following the March 1970 change of government the Khmer Rouge expanded their most effective village defence units into territorial forces, which soon gave way to main force elements. Prince Sihanouk, who had sought refuge in China after being deposed, contributed significantly to their growth by lending his popular support to the Communists: his leadership in the Front Uni National du Kampuchea, an umbrella organisation seeking the armed overthrow of the Khmer Republic, gave the anti-Republican insurgency greater legitimacy in the eyes of the Cambodian peasantry.

Conceived at the Canton Summit of April 1970, the FUNK was envisioned to include three divisions, all to be equipped by China. Imitating the Chinese experience, the insurgents would be a 'People's Army' of popular forces, territorial units, and regulars. In effect, the first FUNK units were composed of hardline Khmer Rouge, FANK defectors, and ethnic Khmer Communists aligned with the North Vietnamese. Training centres were established by the NVA in north-eastern Cambodia and Laos; a headquarters was established at Kratie, a provincial capital whose government garrison deserted soon after the change of government.

From the outset the FUNK was composed of diverse and often antagonistic elements. Prominent were the hardline Khmer Rouge, who had fought Sihanouk since 1967 and advocated an extremist, agrarian, puritan form of 'primitive Communism'. Pol Pot emerged as the leader of these forces, which looked toward China as their main source of support. Also in the FUNK were a small number of intellectuals; FANK defectors; pro-Sihanoukists known as the Khmer Rumdoh; and ethnic Khmer Communists who had closely aligned themselves with the North Vietnamese. The latter two insurgent factions developed in the eastern base areas alongside the NVA, and often maintained North Vietnamese political advisors in their units. By the end of 1970 the FUNK numbered an estimated 15,000 Cambodian insurgents. Further expansion continued over the next year as the NVA eliminated the backbone of the Republican army, allowing the FUNK quietly to build up their forces.

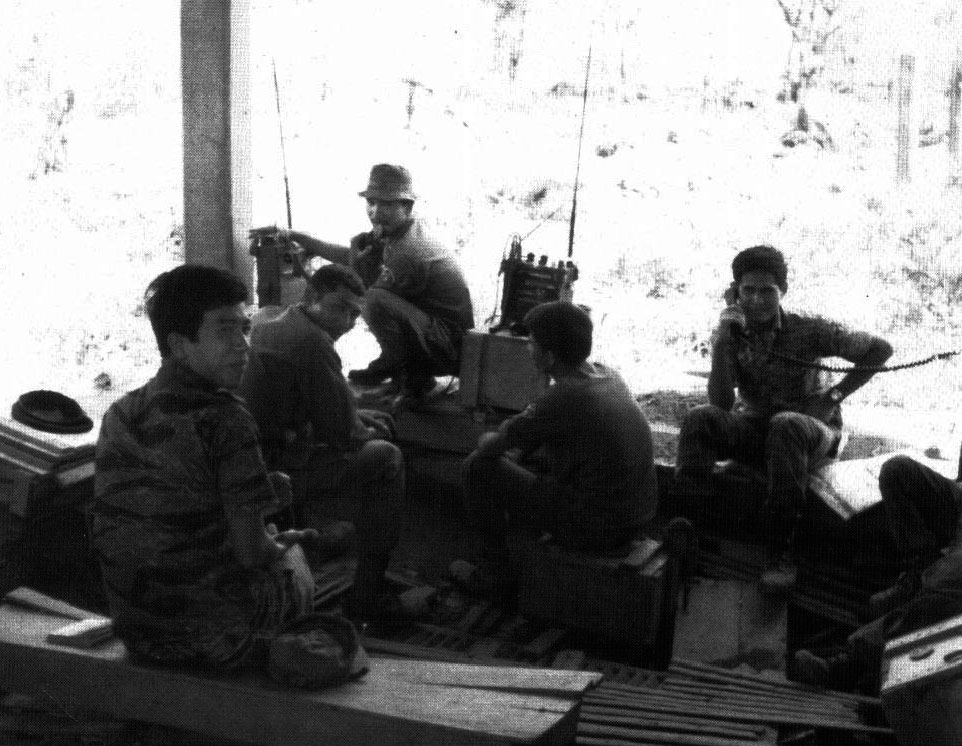

Command post of the 48th Brigade, one of the original Khmer Krom units, during operations on the Bassac River, 27 December 1974.

In 1972 the NVA decreased its force presence in Cambodia, letting the FUNK assume control in the battlefield. The FUNK by that time included some 50,000 regulars and almost 100,000 irregular supports. Throughout the year they fought a war of attrition, striking against government lines of communication and demoralising the FANK.

By January 1973, the FUNK were ready for their first full-scale solo offensive; but when they struck against Phnom Penh, air power devastated their ranks. Suffering heavy casualties, the offensive demonstrated to the FUNK leaders the need to better co-ordinate operations. In June the FUNK launched a second offensive against Phnom Penh using 75 of its 175 available battalions to converge on the capital. Although several positions were overrun south and south-west of the city, the FUNK was again devastated by ground-attack air sorties; up to 16,000 Communists perished during the offensive, with some battalions losing 60 per cent of their manpower. Significantly, most of' the attackers were from the pro-Vietnamese FUNK forces, allowing the hardline Khmer Rouge to consolidate control over the more moderate Khmer Communists.

Two months later, US air support was withdrawn from Cambodia. With the Khmer Rouge in control, the FUNK muted internal dissent and prepared for its 1974 dry season offensive. Communications, command and control, and mobility were still relatively poor, resulting in uncoordinated, piecemeal battles, and the 60,000 FUNK regulars scored no major victories against the government forces.

On 1 January 1975 the FUNK launched its 'Mekong River Offensive'. Converging on the Mekong corridor, the insurgents were able to capture the important river town of Neak Luong on 1 April. Marching north-west from the conquered corridor, the FUNK - numbering some 65,000 regulars in 12 light divisions, 40 regiments, and additional smaller units - began its final assault on the capital. Within two months a co-ordinated Communist offensive had smashed through the FANK outer perimeter and divided the Republican forces into manageable pockets of resistance. On 17 April the Khmer Rouge led the advance into the devastated capital.

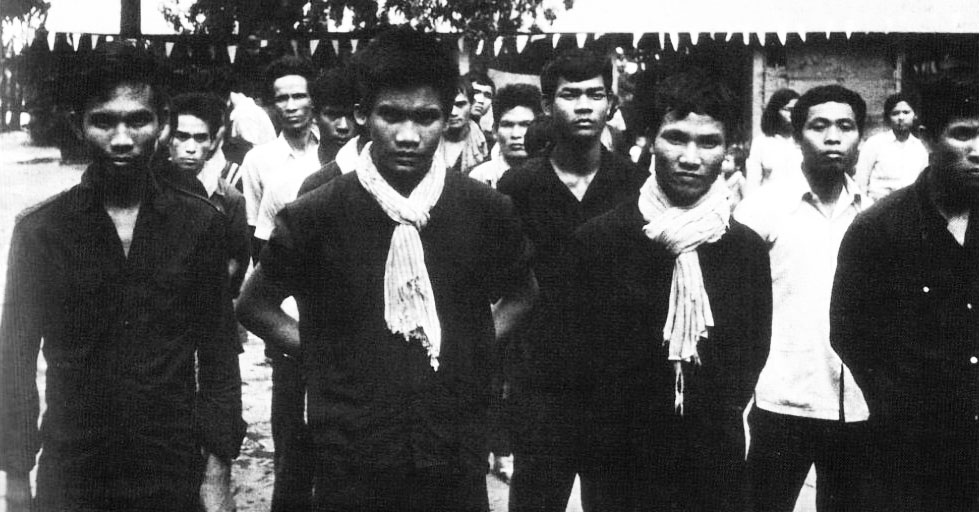

FUNK uniforms and equipment reflected the various ideological backgrounds and foreign sources of support. The Khmer Rouge, which by late 1973 had become the unquestioned power behind the FUNK, wore the most spartan uniform of any Indo-Chinese insurgent group. It usually consisted of a black shirt and pants, often of local manufacture, the shirts often without pockets; pants were frequently rolled to the knee. Women conscripted into the Khmer Rouge, such as the all-female 122 Rifle Battalion, wore black pyjamas as well. Khmer Rouge armoured crews depicted in a propaganda photo next to a Chinese amphibious tank were wearing tank coveralls and helmets supplied by the NVA. (It must be noted, however, that the FUNK never used armoured vehicles in combat against the Republic.)

Other elements of the FUNK deliberately shunned black pyjamas, preferring green NVA fatigues, as worn extensively by the Khmer Rumdoh and pro-Vietnamese elements; others also wore it as a political statement in protest at the extreme, anti-Buddhist views of the Khmer Rouge. Later in the war the Khmer Rouge, too, acquired some uniforms from the NVA. These were often purchased with Chinese funds; because it was more economical, the Chinese preferred to supply the Khmer Rouge with cash for buying uniforms and equipment rather than shipping supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Khmer Rouge defectors, November 1974: most wear the austere black pyjama uniform and red/white krama associated with that grim organisation.

The most common form of headgear was the soft, round, olive drab or khaki 'Mao cap'. Captured FANK patrol caps were also worn, and could be seen on Khmer Rouge lighters on their triumphant march into Phnom Penh. Also commonly worn by the Khmer Rouge was the krama, a peasant scar! worn around the neck or head, most often seen in a red chequered pattern. Footwear was either the rubber sandal or, more often, nothing at all. No branch, unit, or rank insignia existed among the Khmer insurgents.

Khmer Rouge accoutrements were as spartan as their uniforms. Most were of ChiCom origin, purchased from the NVA with Chinese funds. A very common item was the ChiCom AK-47 chest pouch. Khmer Rouge commanders also favoured map cases and holsters as symbols of authority. Later in the war, large amounts of captured FANK equipment allowed the Khmer Rouge to outfit themselves with US web gear and munitions pouches. A small amount of Khmer Rouge equipment was also locally made, such as a crude hammock issued to regular forces.

The Executive Officer of the 1st Parachute Brigade, January 1975, wearing a shirt in French camouflage pattern, French jump wings, and French-style shoulder slide ranking of a lieutenant-colonel.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com