P.D. GRIFFIN

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MODERN BRITISH ARMY REGIMENTS

There is no such thing as the British Army, only a confederation of regiments, hopefully fighting on the same side, all preserving their individuality by being as different from one another as possible.

This observation from a journalist in the twentieth century is as true today as any time in the last 300 years. The enjoyable study of the different regiments that go to make up the British Army may be linked to that shared by collectors of stamps, coins, butterflies, etc. - a fascination with varieties. Regiments and their uniforms had a high profile in the first half of the twentieth century and I have fond memories of glistening soldiers lined up on toy-shop shelves in the grey 1950s, all gleaming red coats and white belts. In time toy soldiers gave way to model soldiers and war games on tables, but in the 1970s war games on fields, courtesy of forming historical re-enactment societies, took us to a new level of appreciation - the Sealed Knot's atmospheric re-creation of the Battle of Naseby drew armies and spectators approaching actual battle strength. Every period in history is represented by these admirable groups, which camp, cook and fight true to the ways of their chosen forefathers, and enthral crowds at home and abroad with their knowledge and skills.

A teenage craze for Napoleon's Grande Armée gradually drifted back to British regiments and their colourful forms shot through with stubborn inconsistencies. Regimental customs seemed to be an aspect that should not be overlooked in any study of this kind, but collecting them proved to be difficult. For practices that can only be seen behind the barrack wall I have had to rely on inside information, and thanks must go to all the regimental secretaries and curators whose correspondence over the past twenty-five years has been so necessary in compiling this book.

Definitions of the word 'regiment' rarely mention the qualities that give, and have given, an identity to the many soldiers whose own regiment was the only family they ever knew.

In an article written in 1989 by a secretary who had 'temped' for the army in Winchester, we are reassured of the idea of the regiment as a family:

The walk across the parade ground, down to the drill square and round the dormitory block was always interesting. There might be a PT display, band practice or parade, and everywhere was scrupulously clean. After the unconsciously accepted litter and filth of everyday life (even in a cathedral city), it was a shock to the system, the order and cleanliness. In the office it was the same; streamlined, efficient, cost-effective, intelligent... There was genuine comradeship between the men, regardless of rank or age or background; between officers and raw troopers probably away from home for the first time; between old comrades from both wars, their widows and children, the would-be officers hoping to join the Royal Hussars once they'd finished at Sandhurst. One and all were held warm and firm in the regimental embrace.

The earliest form of defence in the British Isles depended on villagers and townspeople, who could be called out from their work in times of emergency, but regulated bodies like the Saxon fyrd and the medieval Posse comitatus may be viewed as the seeds of a British army.

Two London volunteer corps of the sixteenth century, the Honourable Artillery Company (HAC) and the Inns of Court Regiment, managed to maintain a fairly continual existence through to the twentieth century, when they became a reliable source of officers for the army in the two world wars. The HAC was raised through a Charter of Incorporation granted by Henry VIII and remains today as a senior regiment of the Territorial Army, uniquely divided with its artillery and infantry sections. The Inns of Court Regiment was founded in 1584 to help protect London against Spanish invasion, and was embodied thereafter in times of emergency. In 1790 it was listed as the Bloomsbury and Inns of Court Volunteers, and in 1860 came through again as the 14th Middlesex (Inns of Court) Volunteer Rifle Corps.

The trained bands of Tudor England were made up of able-bodied men, the best known being the Tower Hamlets Militia, headed by the Constable of the Tower of London. From the trained bands came the county militia, companies of men pressed for readiness to be called up in the defence of their country. The Monmouthshire Militia, which can trace its history back to 1539, also survived the ups and downs of service in peace and war over the centuries and heads the Territorial Army list today.

The musters and drill exercises of the Militia lapsed around 1604 and were not revived again until 1648, at the height of the Civil War. This bitter conflict produced Cromwell's New Model Army, which is often regarded as the origin of the British Army, although Parliament's regiments were disbanded with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Two of them were reengaged in the King's service, however, and live on today in the Guards.

Civil War re-enactment society in the dress of the New Model Army

Two regiments first formed in Scotland under Charles I survived the rigours of seventeenth-century intrigues to be accepted into the army under James II: the Royal Scots and the Scots Guards.

Charles II was the first King of England to keep his regiments banded in peacetime, though he was obliged to class them as his Guards and Garrisons in order to appease a Parliament deeply suspicious of standing armies in the aftermath of the Civil War. His Guards have survived to the present day and their beginnings mark the birth of the army. When Charles took for his bride the daughter of the King of Portugal he acquired by dowry the Portuguese colonies of Tangier and Bombay. Protecting the North African port of Tangier gave the King an opportunity to raise a garrison from which the army gained its 1st Regiment of Dragoons and its 2nd of Foot.

Temporary regiments warranted for home defence in the Dutch Maritime Wars of the 1660s included marines and soldiers recalled from Dutch service. Marine regiments were formed in 1664, 1690, 1702 and 1739, and the permanent Royal Marines were founded under the Admiralty in 1755.

Professional soldiers who had sailed for the Low Countries to fight for the Dutch were required to undergo a test of loyalty during the Maritime Wars, and from those who elected to return to England at this time a regiment was made which was to become famous as The Buffs. A brigade that had gone to Dutch service in 1674 returned with William of Orange in 1688 to be secured as the 5th and 6th Regiments of the line.

Scotland in the seventeenth century was a troubled country plagued by lawless Highlanders and rebellious Covenanters - a strict religious sect, which harboured an armed force strong enough to worry the Scottish government. In 1678 Scotland's parliament raised a small army to keep order, from which emerged two regiments that were to gain a glorious future in the British Army as the Royal Scots Greys and the Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Re-enactment group in the guise of pikemen of the 1680s. Pikes were phased out of the army with the introduction of the ring bayonet around 1690

When James II succeeded his brother Charles to the throne in 1685 the small army he had inherited was enlarged by 200 per cent. Six regiments of horse, two of dragoons and nine of foot were raised in response to the Duke of Monmouth's Rebellion. The superior horse regiments were given precedence over all others that had been raised before them, with the exception of the Horse Guards, but they proved too costly to maintain and the senior regiments were reduced to the rank of dragoon guards in 1746.

By 1688 Parliament was at the end of its tether with King James and his pro-Catholic policies, and Whigs joined Tories to look abroad for a more enlightened monarch. James's Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange were duly invited to come over from Holland to take the crown of England. When William landed in Devon the army went over to his cause and more regiments were organised in the West Country. The deposed James created a following in Ireland and attempted to drive Protestant settlers from the country; the towns of Londonderry and Enniskillen were put under siege and regiments were hastily formed locally in their defence. Two of these continued in service under the title of Inniskilling, a name owed to the slip of a clerk's pen it is said. A sympathetic rising in Scotland during 1689 forced the government to commission regiments of foot to counter rebellions in the Highlands. William harnessed the strength of the Covenanters in a regiment called the Cameronians after their martyred leader Richard Cameron, and in Edinburgh Leven's Regiment lived on to become the King's Own Scottish Borderers.

There followed a lull in recruitment until 1694, when many new regiments of foot were embodied for William's perpetual quarrels with France. A number of marching regiments formed in this year were stood down at the end of hostilities but three - the 28th to 30th of Foot - were re-formed for the new war of 1702. New regiments warranted by William in his last year of life were authorised by his successor Queen Anne and began life as marines.

When Anne died in 1714 the Protestant Elector of Hanover was invited to take the throne and Jacobites again rose up in Scotland. From the regiments formed to fight the rebellion, six were to gain a permanent footing in the army as the 9th to 14th Dragoons. The ebb and flow of campaign in Scotland stretched the old train of artillery to the extent that reorganisation was inevitable, and after 196 years of supervising the artillery and support arms, the Board of Ordnance relinquished its gunners and engineers to form their own separate bodies, each responsible for their own area of expertise.

When George II succeeded to the throne in 1727, Scotland was still an unsettled country and independent companies of Highlanders recruited from families loyal to the crown were hired to police the braes. Those patrolling to the north of Glasgow were known by their dark tartan as Am Freiceadan Dubh (the Black Watch), a name later adopted by the army's first Highland regiment to be enlisted after the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715. Lads for the Highland Regiment joined up in the belief that they were wanted for service in their own country and when they were ordered over the border in 1743 a hundred of them turned back, only to be hunted down and returned to London where the ringleaders were shot and the remainder transported. In the ensuing years some sixty Highland regiments were raised in times of war, and of these, seven line and nine fencible regiments were to mutiny against harsh conditions and broken promises.

Several marching regiments were raised with the outbreak of war in 1740, seven of which remained with the infantry. At this time regiments were identified by the name of their colonel but around 1751 a system of numbering according to seniority gave them a more permanent identity.

The 1750s found Britain and France locked in conflict around the world, and in Europe Frederick the Great was expanding Prussian territory into neighbouring countries. Existing regiments were brought up to war strength, more were commissioned, and, after the usual disbanding and renumbering at the end of the war, twenty-one new formations could be added to the army list: the 50th to 70th Regiments of Foot.

As the Seven Years War progressed, an experiment with light cavalry proved so successful that complete regiments of the kind were formed for service in the period 1759-60. All but three of the new light horse regiments were disbanded at the end of the war, but the concept thrived and eventually most of the heavy dragoon regiments were converted to a light role as hussars or lancers.

A Militia Bill passed during the Seven Years War to resurrect the old county militia regiments was implemented with a threat of invasion in 1759. It required a quota of able- bodied men to be chosen by lot in every county of the land, to be drilled in town and village every week from spring until autumn, ready to be called out when needed. The men proved quite willing when danger threatened but seldom looked to their duties after the end of the French wars.

Re-enactors in the dress of the Marlburian Wars 1703-12. The black felt hat of the last century was now turned up on three sides

The early part of the reign of George III was dominated by unrest in the colonies fought over in the Seven Years War. Riots and demonstrations in Massachusetts sparked a revolution that was to tie down the army for ten years and end in defeat. The surrender of a British column at Saratoga in 1777 stirred people at home to form volunteer units for local defence in case news from the colonies influenced French policy against England. In general English soldiers had little taste for fighting their own countrymen in America, but the Highland Scots had suffered great poverty after their defeat at Culloden in 1746 and gladly offered their services under arms for the King's pay. The next twenty years saw the birth of the remaining Highland regiments of the British Army.

In 1787 intelligence was received that the Sultan of Mysore had made contact with French forces to converge on British interests in India, resulting in a hasty commissioning of four battalions to reinforce the Honourable East India Company's brigades in that region. These formations achieved status as the 74th to 77th Regiments of Foot.

The turbulent age of rebellion culminated in the French Revolution of 1789. The security of Britain was threatened and when the revolutionary government of France declared war in 1793 rumour spread that her citizen army was preparing to invade and a state of panic ensued. Parliament made an urgent survey of Britain's defences and found her Regular Army strung out across the world, the militia weak and inefficient, and most able-bodied men of poor birth more likely to collude with a revolutionary invader than repel him. Pitt the Younger took up the challenge and led his party to enlarge the militia and accept the offers of volunteers to serve under arms in the defence of their homeland. Permanent regiments of infantry raised in the period 1793-4 were placed as the 78th to 92nd of Foot.

Re-enactment group in the mid-eighteenth- century dress of a regiment of foot. The officer and 'battalion men' wear the tricorne of the period, whereas the tall grenadiers sport a cloth mitre cap to make them look even more imposing

The French Revolutionary War carried the army to Flanders, where great suffering in the winter of 1794 prompted the Duke of York to create a Corps of Waggoners to take the necessary supplies to the army in the field. The corps served throughout the Napoleonic Wars and was reconstituted in Victorian times as the Army Service Corps. A similar want of mobility in the artillery at the time prompted the birth of the Royal Horse Artillery. When invasion threatened, men not already committed to the militia felt the need to volunteer for the many armed associations that were springing up around the country, and gentlemen of the middle classes and yeomen farmers got together to meet the aggressor with troops of volunteer cavalry.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, lapels and cuffs had narrowed and the tricorne was flattening out to bicorne dimensions

Most of these were put together to form regiments of Yeomanry Cavalry during the Napoleonic Wars, and the majority remained in service after the wars to provide an aid to the civil powers in the industrial, political and agricultural riots of the nineteenth century. In 1899 the new war in South Africa needed cavalry to cover the vast expanses, and brigades of yeomanry were formed to serve abroad for the first time.

A member of the Napoleonic Association in the infantry uniform of 1800-12

The turn of the eighteenth century saw the emergence of a new elite among the infantry: riflemen dressed in green and armed with the short Baker rifle instead of the long, less accurate, musket of the redcoat regiments. These skirmishers proved their worth on the battlefield and inspired many volunteer units to emulate them.

In the long peace which followed the Battle of Waterloo, junior regiments of cavalry and infantry were disbanded and the militia served to exist in name only. Only the demands of the empire forced the formation of new regiments; these appeared in 1824 and ranked as the 94th to 99th Foot.

An act of 1852 called for the resurrection of the militia for the defence of the realm, this time manned by volunteers and not enlisted by lot. They were clothed as ever in the red coats of the regular infantry, though a trend towards green-coated riflemen was growing, and many more militia regiments than before were electing to take Light Infantry or Rifles titles.

Russian aggression in the east led to an Anglo-French coalition and the embarkation of an army to the Crimea in 1854. The rigours of the Crimean War so far from home highlighted deficiencies in transport, stores and supplies, policing and hospital services. Departments were formed in 1855 to meet these needs.

In 1857 Indian regiments serving alongside European regiments under the control of the Honourable East India Company (HEIC) mutinied, and the resulting campaign to restore order and discipline ended with India being taken under direct rule of the crown and the HEIC regiments transferred to the British Army. The cavalry took their post as the 19th, 20th and 21st Hussars and the infantry came in as the 100th to 109th Foot.

During 1859-60 the towns and counties of Britain were authorised by the Secretary of State for War to raise volunteer units to cover the new threat of French aggression, and a multitude of corps, largely infantry, emerged and flourished as rifle clubs in uniforms of grey or green. Unlike previous volunteer regiments, the rifle volunteers continued to train after the threat of war had passed and, in the 1880s, found themselves seconded to the regular county regiments as their volunteer battalions.

The year 1881 saw the first mass amalgamations of the regiments, when the Cardwell Reforms organised 109 regular infantry and 121 militia regiments into 69 district regiments. Around this time more support corps were created to take responsibility for physical training, nursing, veterinary care and pay in the army.

In 1908 all army volunteers were grouped under the heading of the Territorial Force. This covered yeomanry, volunteer battalions of regular infantry regiments and five independent regiments: the London, Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Herefordshire and the Monmouthshire. After the First World War, the 'Territorials', who had given so much in the conflict, were reorganised as the Territorial Army, but many units were then re-roled or disbanded.

The First World War brought forth new corps in the sciences of tank warfare, weaponry and signalling, but the old arts of war had taken a knock, and in 1921 eighteen regular cavalry regiments were reduced, and paired off as nine 'new' regiments. In the same period five Irish infantry regiments were disbanded with the birth of the Irish Free State.

During the 1920s and 30s most of the army's horse regiments were converted to armoured vehicles, and the Second World War saw the need for airborne regiments and more support corps. The Auxiliary Territorial Service enabled women to serve in trades hitherto reserved for men.

The reign of Elizabeth II will be remembered in the army as a time of great reductions in the armed forces. In the 1950s infantry regiments were organised into brigades, which were to act as a basis for amalgamations. This was visited on twenty-four regiments between 1958 and 1961. The Army Council's decision to make large regiments from the infantry brigades was implemented in 1964 with the Royal Anglians, but in 1968 two old regiments, the Cameronians and the York and Lancasters, were disbanded as the junior regiments of their brigades.

Late Victorian infantry as portrayed by the Die Hard Company. The infantry pattern helmet replaced the shako in 1878

In 1992 the government's Options for Change scheme meant another wave of amalgamations, which involved support corps as well as regiments, and in 2004 the Ministry of Defence asked for further cuts in manpower to fund new technology and the remaining small (single battalion) regiments were drawn down' to be restructured into larger but fewer infantry regiments by 2007.

The regiments and corps of the Regular Army are listed in order of precedence according to the army's old class system where seniority does not always bring priority:

1. The Household Cavalry, seniority over all other regiments given to the Horse Guards by a royal warrant of 1666.

2. The Royal Horse Artillery, formed in 1793 but placed ahead of the cavalry in the Queen's Regulations of 1873 because its parent regiment (see class 4) had priority over the infantry.

A First World War re-enactment group in the universal khaki service dress issued in 1904. Full dress was suspended with mass enlistment in 1914

3. The Royal Armoured Corps, formed in 1939 with the inherited seniority of its cavalry regiments, which were given status second only to the Horse Guards in 1713. Dragoon Guards have precedence in the corps and regiments are listed by the seniority of their oldest antecedent.

4. The Royal Regiment of Artillery, promoted ahead of the foot regiments in 1756.

The Corps of Royal Engineers, grouped with the RA for its parallel history.

The Royal Corps of Signals, placed under its parent corps, the Royal Engineers, although actually far more junior than this classification.

5. The Foot Guards, displaced from their rank next to the Horse Guards in 1713.

6. Infantry regiments, listed by the seniority of their oldest antecedents.

7. Support corps other than those in class 4 (listed in order of seniority).

8. The Territorial Army (regiments listed in the order of their affiliated regular regiments and corps).

THE HOUSEHOLD CAVALRY REGIMENT

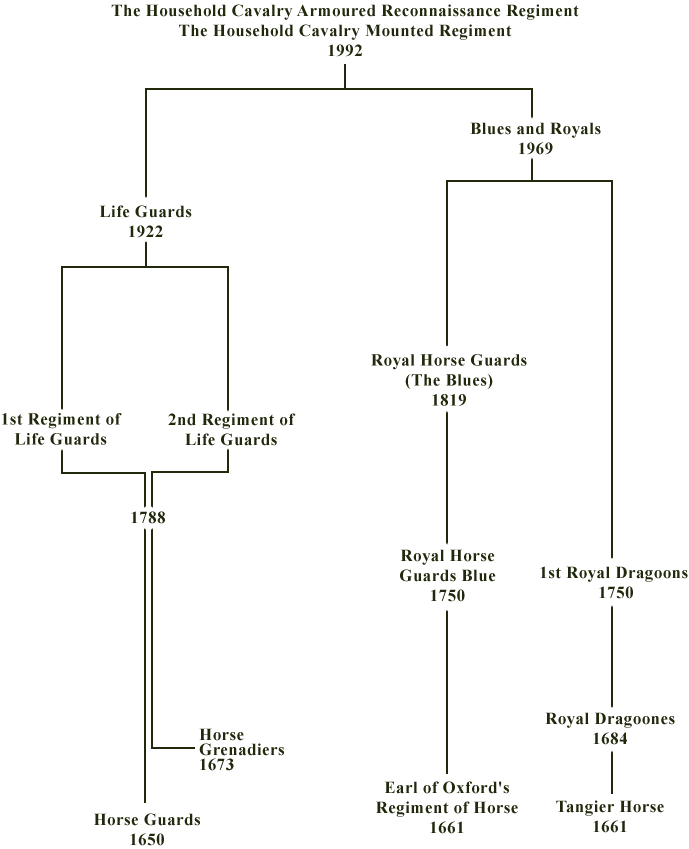

This, the most senior of all British Army units, is a mix and match of two complementary regiments of Horse Guards that, since 1820, have served together as Household Cavalry, a term rooted in the royal household that they guard. The Life Guards were the first to have this exalted honour and have always headed the army list. The Blues and Royals are the product of the 1969 union of the Royal Horse Guards (nicknamed 'The Blues' from their distinctive coats) and the 1st Royal Dragoons ('The Royals). All three regiments have London backgrounds and date back to the reign of Charles II.

The armoured squadrons based at Windsor fulfil the regiments' modern role, whereas the ceremonial mounted squadrons - the only true cavalry left in the army - operate their historic public duties from Hyde Park Barracks, home to the Life Guards since 1795.

Household Cavalry bands in mounted review order, Blues and Royals to the fore

The blue forage cap has the scarlet band of royal regiments and a Guards' pattern peak with gold braid according to rank: troopers and musicians one row, lance corporal ranks two rows, corporals of horse three rows, squadron quartermaster corporals four rows and corporal major five rows. The rank of sergeant is not used in the Household Cavalry because of the word's origin in 'servant' and the Horse Guards' high-bred traditions. The HC cap badge shows the sovereign's cypher within a crowned Garter belt inscribed with its motto Honi soit qui mal y pense (Shamed be he who thinks evil of it).

On the khaki service dress cap a similar badge is worn, which first appeared in 1914: the cypher within a circle is inscribed with the title of the regiment, customarily bright in the Life Guards and bronzed in The Blues and Royals.

Rank chevrons, uniquely made of gold wire for HC No. 1 dress, are worn with a crown above. This custom dates from 1815, when the Prince Regent sent a box of small silver crowns to the Horse Guards to show his appreciation of their part in the great victory at Waterloo.

Troopers of the Life Guards, 1997

The HC Mounted Regiment and bands are issued with traditional HC full dress. The 1842 white metal helmet is fitted with a white plume for the Life Guards, a black plume for farriers of the Life Guards, and a red plume for trumpeters of the Life Guards and all members of The Blues and Royals. The 1856 pattern tunic is scarlet with blue facings for the Life Guards and blue with scarlet facings for The Blues and Royals, and farriers of the Life Guards. Farriers historically wear a contrasting uniform to the rest of their regiment. A buff white cartouche belt is worn over the shoulder with its red flask cord, a relic of the eighteenth century when powder had to be carried for the musket. Farriers wear an axe belt in lieu of the cartouche belt and carry a polished axe on parade to symbolise their historic role in dispatching horses wounded in battle. Commissioned and noncommissioned officers have a system of gold aiguillettes, which are worn from the shoulder of the full dress tunic to indicate rank, a HC custom from the reign of George IV. The blue overalls are regimen tally marked - a wide scarlet stripe in The Blues and Royals, a double scarlet stripe with a central welt of the same colour in the Life Guards (ex-2LG from 1832).

In Mounted Review Order, HC dress is shown in all its unique glory: white leather gauntlets and buckskin breeches with tall jackboots, all dating from 1812, and a polished silver nickel cuirass (from 1821) worn over the tunic. This heavy weight on large black horses inspired the nicknames 'Bangers' and 'Lumpers'. Musicians and trumpeters are privileged to wear the crimson and gold state coat in the presence of royalty, and the crimson state cloak in bad weather.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com