J. ARNOLD, S. SINTON, illustrated by DARKO PAVLOVIC

US COMMANDERS OF WORLD WAR II. NAVY AND USMC

The Constitution of the United States gave the president supreme control over all armed forces. Before and during World War Two, President Franklin D. Roosevelt served as president and commander-in-chief. A civilian served as Secretary' of the Navy and exercised control of the navy and marines through the Navy Department and its bureaus. A navy board provided expert military advice to the secretary. At the time Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the highest post in the navy, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), was held by Admiral Harold Stark.

The outbreak of global war revealed the pressing need for a stronger civilian-military command structure and army-navy cooperation. Consequently, in February 1942, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) replaced the Joint Board as the highest military authority. Among the four original members of the JCS were Admirals Ernest King (Commander-in-Chief, US Fleet) and Harold Stark. When Stark was reassigned in March, the position of Chief of Naval Operations was merged with King's position. In July, the balance on the JCS of two admirals and two army officers was restored when Roosevelt appointed Admiral William Leahy to become JCS chairman as well as chief of staff for the president. Leahy's excellent relations with Roosevelt ensured that the JCS became the dominant military planning organization. The JCS both controlled the nation's armed forces and advised the president on everything from strategy to industrial policy.

A Japanese pilot's view of Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941 shows the US fleet at anchor with smoke rising from Hickam Field in the distance. (National Archives)

In 1939, the US Navy had 15 capital ships, five carriers, 18 heavy cruisers, and 19 light cruisers. It held its own aviation assets, which included carrier planes and land-based sea patrol planes. In February 1941, planners established both an Atlantic and a Pacific Command in order to conduct naval warfare simultaneously in both oceans. Admiral King commanded in the Atlantic while Admiral Husband Kimmel took command of the Pearl Harbor-based Pacific Fleet. The surprise strike against Pearl Harbor led to changes in the naval command structure. Most importantly, Admiral Chester Nimitz succeeded Kimmel as Commander-in-Chief Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC). He reorganized his command into three geographic zones: North Pacific, Central Pacific, and South Pacific. Because Nimitz's Central Pacific offensive diverged from MacArthur's drive toward the Philippines, the Joint Chiefs of Staff provided the necessary coordination. Leading the offensive were the numbered fleets such as Halsey's famous 3d Fleet. Thev had varying strengths, with their offensive strength organized into task groups and task forces. In the Pacific, fast carrier task forces provided the dominant striking force. Consequently, carrier admirals quickly became the key naval leaders. Statistics clearly show the colossal expansion of naval aviation. Between June 1940 and the end of the war, the number of naval air personnel rose from 10,923 including 2,965 pilots, to 437,524 including 60,747 pilots.

The US Marine Corps (USMC) was a separate service under the Navy Department. Unique among marine forces, the USMC also operated its own aviation force. The Corps Commandant was the highest-ranking active marine officer, with his own headquarters and staff. September 1939 found the 20,000-strong Marine Corps with two Fleet Marine Forces. These forces were specially trained in amphibious landings and each was supported by an aviation group. One of these brigade-sized forces was stationed on the Atlantic coast and one on the Pacific. In February 1941, they were expanded to become full-sized divisions, each with an associated Marine Aircraft Wing. A corps headquarters provided administrative support. Later in the war, such headquarters were redesignated as Amphibious Corps and became the planning headquarters for amphibious operations. The Marine Corps expanded to six marine divisions during the war. The corps' aviation group grew from 641 pilots and 13 squadrons to 10,049 pilots and 128 squadrons.

Husband Edward Kimmel was the son of a West Point graduate who had fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. Born in Henderson, Kentucky, in 1882, Kimmel graduated from the US Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1904. He served as an ensign at sea and then did postgraduate study in gunnery. During the decade before World War One, Kimmel earned a solid reputation as a gunnery and ordnance expert. He served primarily aboard American battleships. Kimmel received a wound during the Vera Cruz occupation in 1914. The next year, he served as an aide to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin Roosevelt. When the United States entered the war, Kimmel went to Great Britain to advise the British about new methods for gun spotting. He then served as staff gunnery officer for the American battleship force that operated with the Royal Navy.

During the interwar years, Kimmel steadily climbed in rank while serving in a variety of staff and ship commands. He burnished his reputation as a professional sailor who displayed energy and drive. Between 1939 and 1941, he commanded first a cruiser division and then all of the cruisers assigned to the Pacific Fleet's Battle Force. His outstanding performance led to his promotion, over the heads of many senior (lag officers, to full admiral in February 1941 and commander of the Pacific Fleet. Admiral Stark told Kimmel around this time that "the question of our entry into the war now seems to be when, not whether." In the months before Pearl Harbor, Kimmel prepared the fleet for war with Japan through a series of rigorous training exercises.

Kimmel expected war with Japan but believed it would begin elsewhere, probably in the Philippines. The Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor totally surprised him. Recovering quickly, he planned to use his three carriers to relieve the beleaguered garrison on Wake Island. Instead, he himself was relieved of command on December 17, 1941. The special commission that investigated Pearl Harbor found Kimmel guilty of "dereliction of duty." The finding compelled Kimmel to resign in disgrace. A navy court of inquiry in 1944 found Kimmel not guilty, but Admiral King reversed the verdict. King ruled that he had made serious mistakes by not ordering sufficient air patrols and had shown that he "lacked superior judgment necessary for his post." Modern critics assert that Kimmel should have realized that war could come at any time and that he failed to take the steps to keep his command alert. Kimmel's defenders argued that Washington had withheld important information and then used him as a scapegoat to cover up the failings of his superiors. More recently, some historians have alleged that Roosevelt deliberately withheld information from Kimmel in order to facilitate the Japanese strike and thus drag the United States into war. This controversy continues, although most serious historians find the evidence of Roosevelt's duplicity unpersuasive.

Kimmel had the great personal misfortune to be the commander on the spot on December 7, 1941. He must, therefore, assume responsibility. As one historian wrote, "While he was not always well served by authorities in Washington, he was not prepared for war when it came." Kimmel died in 1968.

Born in 1878 in Lorain, Ohio, Ernest King graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1901. Before graduation, he managed to outflank normal protocol and secure a position aboard a cruiser that saw action in the Spanish American War. During the years leading to World War One, King served in a variety' of technical and administrative positions and commanded destroyers. He accompanied the Atlantic Fleet to Europe when the United States entered the war. He attended planning sessions and acquired a profound understanding of the complexities of multinational strategic planning. He also developed a mistrust of both the British and all bureaucracies. After the war, his abrasive personality impeded promotion.

Admiral Husband Kimmel was the senior naval officer present at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. In his capacity as commander of the United States Pacific Fleet, he received much blame, some justified, some not. Following the successful British torpedo attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto, the Secretary of the Navy suggested to Kimmel that an anti-torpedo net barrier be placed around Battleship Row. Kimmel rejected the idea because it "would restrict boat traffic by narrowing the channel." Such lack of foresight cost Kimmel his job ten days after Pearl Harbor. (National Archives)

Sensing the growing importance of air warfare, King qualified as a naval aviator in 1928. He graduated from the Naval War College and became Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. This position taught him a great deal about government spending as he successfully lobbied for funding of aviation programs. When President Roosevelt sought a qualified flag officer who was also a pilot, the only choice was King. Consequently, he promoted King to rear admiral in 1933. By 1938, King was a vice admiral in command of the Pacific Fleet's carriers and land-based aircraft. He urged the development of fast carrier and battleship squadrons, but the navy's orthodox thinkers ignored him.

Facing apparent retirement. King's great chance came in 1940 when he served with the Secretary of the Navy on a fact-finding mission. He impressed the secretary who, in turn, urged President Roosevelt to appoint him to command the Atlantic Fleet as a four-star admiral. This gave King a direct link to Roosevelt and led to his appointment to the Combined Allied Staff. As part of the major shake-up in the navy's senior command, following Pearl Harbor, King became Commander-in-Chief of the US Fleet. This post overlapped with the Chief of Naval Operations, so in March 1942 Roosevelt gave King enormous powers by appointing him to both positions. He became the first officer to hold the navy's two most senior positions simultaneously. In this capacity, King also represented the navy on the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

King believed that the Pacific Theater should get first call on military resources. This belief led him into frequent disputes with advocates of the "Germany first" strategy. His blunt, candid, and domineering personality caused frequent clashes with numerous American and Allied leaders. His daughter explained that King was "even tempered, he's just mad all the time." With King in attendance, strategic debates often became heated and led to personal antagonisms. In particular. King and General "Hap" Arnold, the air force representative on the Joint Chiefs of Staff, did not get along very well. However, King knew that the Joint Chiefs of Staff had to cooperate to prosecute the war effectively, and that was always his overriding goal.

After Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Admiral Ernest King wrote, "The way to victory is long. The going will be hard. We will do the best we can with what we've got. We must have more planes and ships - at once. Then it will be our turn to strike. We will win through - in time." King's determination helped the navy through the difficult, early war days. His insistence on procuring the best ships and planes that money could buy, at prices within the nation's budget was a key factor in overcoming obstacles to the navy's expansion. His fixation on the Pacific Theater interfered with overall Allied strategy. His difficult personality led Roosevelt to joke that he "shaved with a blow torch." (National Archives)

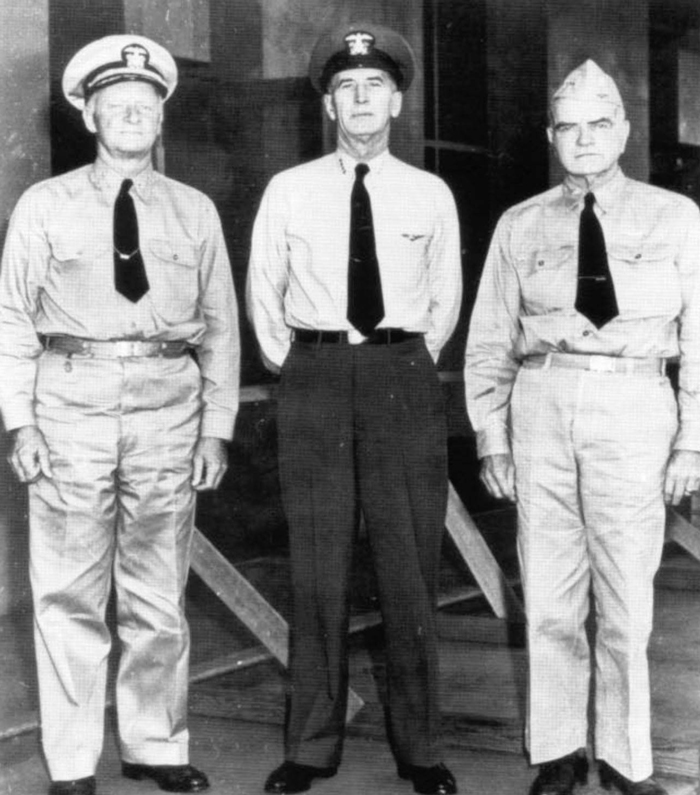

This picture shows three architects of victory in the Pacific: Admiral King (center) with his two key subordinates, Admiral Nimitz (left) and Admiral Halsey (right). (National Archives)

Still, the fierce competition for resources led to repeated bureaucratic battles. During the planning for an attack in the Solomon Islands, the army-navy feud became so heated that King warned General George Marshall that he would order the operation to proceed "even if no support of army forces in the southwest Pacific [MacArthur] is made available." At the January 1943 Casablanca Conference, King wanted a larger share of the rapidly expanding store of Allied resources committed to the Pacific. He and Marshall proposed that 30 percent of Allied resources go to the Pacific, China, Burma, and India. The real issue was not the total, but rather the amount, of scarce, critical resources: landing craft, heavy bombers, ocean escort ships, and cargo shipping. The British were more interested in Europe than the Pacific and skillfully avoided categorical responses to King's plan. During a heated argument, King suggested that after the United States aided Britain in Europe the British would fail to help the Americans in the Pacific. Prime Minister Winston Churchill interceded to promise that this would not happen. Because of King's arguments, the Combined Chiefs agreed that there should be no let-up in the pressure against Japan. King informed Nimitz that the US Chiefs of Staff had convinced the British "of the fact that there is a war going on in the Pacific and that it had to be adequately implemented even though the major operation continues in Europe."

King's efforts at Casablanca did not address the problems of the divided command in the Pacific. According to boundaries on the map and prior plans, after the capture of Guadalcanal, the next offensive would occur within MacArthur's jurisdiction. However, after great effort, the navy had assembled a powerful fleet in the Solomons and it did not like the idea of handing over operational responsibility to a general. This type of inter-service rivalry plagued operations in the Pacific until the war's end, and Ring did little to resolve it. He also continued to dispute with British strategists over the proper conduct of the war. This caused him to prod Nimitz to rush preparations for operations in the Central Pacific. He informed his staff that they must hurry "so that the British could not back down on their agreements and commitments. We must he so committed in the Central Pacific that the British cannot hedge on the recall of ships from the Atlantic." The marines paid with their blood at Tarawa for this demand for haste.

Marines struggle ashore on Tarawa in November 1943. Among many difficult, bloody island invasions, Tarawa was the hardest. (National Archives)

On the other hand, King was instrumental in forcing the navy to develop the fleet train concept: the ability to supply and repair ships without returning to a home base. The fleet train, in turn, allowed wide- ranging carrier raids and amphibious landings that bypassed numerous Japanese strongholds. King was convinced that the destruction of Japan's fleets alone would not bring victory. He believed that the Chinese coast would have to be secured to provide a base for the aerial bombardment and subsequent invasion of Japan. He clung to this view until the end of the war and, thus, opposed General Douglas MacArthur's strategy regarding a return to the Philippines.

However, King viewed with skepticism the notion that strategic bombing operations alone could win the war. The B-29s would have to fly from islands captured by the navy and the marines. One of King's staff officers observed, "The interests of the AAF [Army Air Force] and the Navy clash seriously in the Central Pacific campaign." The navy worried that it would be relegated to a secondary role, namely capturing bases from which the air force would win the war.

Tough and outspoken throughout his career, King retired in December 1945 and died in 1956. King shares responsibility with Marshall for failing to unify command in the Pacific. Pacific operations remained unwisely divided between the navy under Nimitz and the army under MacArthur. The two-prong advance against Japan gave the Japanese the opportunity to concentrate forces to defeat the widely separated American efforts. Fortunately, the Japanese failed to seize the chance. King was one of the most influential strategic planners on the Allied side. He commanded a force through difficult times and oversaw its expansion into the world's largest navy with over 8,000 ships, 24,000 aircraft, and 3,000,000 people. The prevailing historical judgment is, "No other officer has had such complete authority over so large a navy institution and few could have wielded it so well."

Chester William Nimitz was born in Fredericksburg, Texas, in 1885. After first applying to West Point, Nimitz instead entered the US Naval Academy at the age of 15. He graduated in 1905. Nimitz began his career in unpromising fashion by being seasick during his first voyage. He ran his second command, a destroyer, aground and received an official reprimand. Nonetheless, by the time of World War One, Nimitz had risen to chief of staff to the commander of the Atlantic Fleet's submarine division. Between the wars, Nimitz graduated from the Naval War College, served on a variety of capital ships, and taught naval science at the University of California. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor found him as Chief of the Bureau of Navigation.

Nimitz had received serious consideration in 1940 for the command of the Pacific Fleet. Thus, when the Roosevelt administration decided to make Admiral Husband Kimmel a scapegoat for Pearl Harbor, the choice to replace him naturally fell on Nimitz. Nimitz arrived at Pearl Harbor on Christmas Day 1941. As he motored across the harbor, he saw naval craft collecting bodies as they floated to the surface from the doomed ships on the harbor bottom.

The Commander-in-Chief Pacific Fleet was responsible for an immense area. In violation of the principle of unity of command, the Pacific was divided into two theaters. MacArthur was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Southwest Pacific Area. This area embraced Australia, the Philippines, the Solomons, New Guinea, the Bismark Archipelago, Borneo, and all of the Dutch East Indies except Sumatra. Nimitz commanded everything else in the Pacific except the coastal waters of Central and South America. This vast area received the designation, the Pacific Ocean Areas. Holding the rank of full admiral, Nimitz also retained command of the Pacific Fleet.

Nimitz confronted the challenge of rebuilding his demoralized fleet and protecting American interests in the Pacific with great skill. The fleet s air arm and its submarine force remained intact after Pearl Harbor. To restore morale and keep the Japanese off balance, Nimitz, a former submarine expert, ordered unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan. Nimitz reorganized the surface fleet into task forces centered on fast aircraft carriers. With the support of Admiral King, he began planning offensive action involving carrier raids. At this time, most senior naval officers believed that it was too risky for carriers to attack heavily defended land bases. The senior earner admiral, William Halsey, supported Nimitz and ottered to lead the first attacks. The subsequent raids accomplished little in strategic terms but they were important in raising morale, providing experience, and developing tactics.

Admiral Chester Nimitz utilized his resources aggressively. Still, he soberly recognized the gravity of the situation around Guadalcanal during the late summer and fall of 1942. Following the devastating Japanese battleship bombardment of Guadalcanal, on October 15 Nimitz assessed the situation: "It now appears that we are unable to control the sea in the Guadalcanal area. Thus our supply of the positions will only be done at great expense to us. The situation is not hopeless, but it is certainly critical." (National Archives)

Relying upon intelligence intercepts, Nimitz aggressively employed his scarce earners to intercept the Japanese at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942. Before that .battle, he confidently observed that "because of the superiority of our personnel and equipment" the United States could take the risk of fighting the Japanese even when facing adverse odds. This proved to be an overly sanguine view. Still, the drawn battle was a useful propaganda victory and marked the first strategic check to Japanese expansion.

Nimitz's superb intelligence teams predicted another Japanese thrust against Midway Island. Nimitz was determined to parry this thrust but the fleet was critically short of carriers. When the badly damaged Yorktown arrived at Pearl Harbor on May 22, Nimitz and the navy's technical experts sloshed around the dry dock to inspect the vessel. The best estimate was that repair would take 90 days. Nimitz told shipyard technicians, "We must have this ship back in three days." On the morning of May 29, the Yorktown departed to join the forces that intercepted the Japanese at the decisive Battle of Midway.

Nimitz supervised the Solomon Islands campaign in late 1942 and early 1943. Thereafter, the rapid buildup of American strength permitted offensive actions on a much larger scale. Nimitz endorsed the "island-hopping" strategy that bypassed many Japanese strongholds, leaving them to "wither on the vine" during the inexorable advance against the Japanese homeland. Through it all, Nimitz continued his aggressive leadership, as illustrated by the drive into the Central Pacific. While the battle for the Gilbert Islands was taking place, American planners considered the next step: the invasion of the Marshall Islands. Nimitz's chief planning officer suggested a bold stroke: a strike against Kwajalein Atoll in the center of the island chain. Nimitz concurred. Citing the apparent enormous risks, General Holland Smith and Admirals Kelly Turner and Raymond Spruance vehemently disagreed. After a heated meeting on December 14, 1943, Nimitz polled his subordinates. They all said Kwajalein was a mistake. Directing his comments to Turner, Nimitz responded, "This is it. If you don't want to do it, the Department will find someone else to do it." The dissenters obliged.

The decisive Battle of Midway occurred because American strategists used their intelligence wisely. Admiral Nimitz observed: "Had we lacked early information of the Japanese movements, and had we been caught with carrier forces dispersed ... the Battle of Midway would have ended differently." Nimitz well understood how US hopes depended upon a small handful of fleet carriers. This shows some of the damage suffered by the Yorktown at Midway. (US Naval Historical Center)

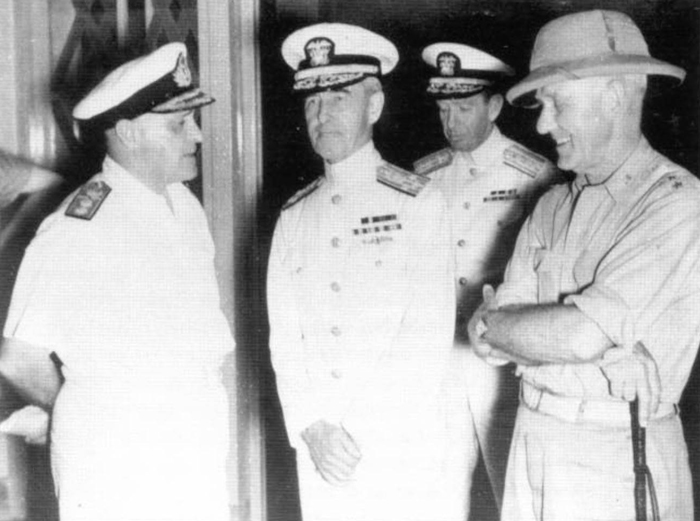

Admiral Thomas Hart (second from left) doubted that the Dutch East Indies could be held in the face of Japanese air superiority. Hart meets with the British Admiral Layton (left) on Java in a futile effort to coordinate an effective defense. (The George C. Marshall Research Library, Lexington, VA)

The successful capture of the Gilberts and Marshalls demonstrated how fast-carrier operations could support amphibious invasions in wide- ranging operations. Nimitz turned his attention to an attack on the Marianas in order to provide a base to bomb the Japanese homeland. Palau and the Philippines came next. Nimitz advocated bypassing the Philippines in favor of an invasion of Formosa. Daunting logistics and MacArthur's political influence helped persuade Roosevelt to overrule Nimitz and order the invasion of the Philippines. In December 1944, Nimitz received promotion to fleet admiral, a rank that made him equal to MacArthur. The two great leaders had cooperated well in the past and this cooperation continued to the end of the war.

Nimitz ended the war as a hugely popular and respected leader. He succeeded Admiral Ernest King as Chief of Naval Operations for a two- year stint that ended in 1947. In this capacity, he won an important bureaucratic victory by opposing the proposed consolidation of the army and navy. He retired in December 1947 and died in 1966.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com