MARK R. HENRY, MIKE CHAPPELLTHE

US ARMY IN WORLD WAR II. NORTH-WEST EUROPE

Women's Army uniforms were almost universally condemned for their poor fit and appearance. By VE-Day, however, they had some of the most practical and best-looking uniforms of any of the women's services. The 1942 drab service dress for enlisted WAACs/WACs consisted of a hip-length tunic with four brass buttons, in the same drab brownish colour (OD shade 54) as used by male personnel. It had scallop-flapped internal breast pockets and plain slashed lower pockets. A skirt reaching to just below the knee, and the stiff-billed 'Hobby' hat, were both in matching drab brown (see also MAA 342, Plate B2). A russet brown shoulder-purse was issued to be carried with this uniform. WAAC/WAC officers wore the same general style of uniform as the enlisted women. Their coat and hat were made of wool barathea in the Army officers' dark green/chocolate colour (OD shade 51), and worn with a skirt made in the colour of officers' 'pinks'. The first coat issued had transverse shoulderstraps and an integral belt; the later model had normal epaulettes and no belt. In service dress, WACs wore sensible russet brown laced low-heel shoes, and sometimes brown gloves.

With the 1943 enrolment of the Auxiliaries of the WAAC into the regular Army the new Women's Army Corps dropped their 'walking buzzard' insignia in favour of the standard US eagle. They retained the use of the Athena head branch insignia, though many WACs serving with a specific branch - e.g. the Air Corps - wore that collar insignia instead.

In late 1944 WACs in Europe followed the current fashion, receiving a specially designed 'Ike' jacket with a matching skirt, trousers, and an overseas cap of more curved shape than the men's (see Plate Dl). This jacket was modelled on the CI issue field/service jacket, both with and without breast pockets. It was made in both enlisted drab and officer's dark green/chocolate colours, and proved very popular. Like the men's version, the WACs' short jacket soon became the standard issue for the 'CI Jane'.

An off-duty dress was authorised in 1944 consisting of a fairly plain-looking, long-sleeved, knee-length dress of wool crepe. This came in both beige (summer) and dark khaki (winter) colours; it had concealed buttons, a belt, patch breast pockets and epaulettes. Basic branch insignia were worn on the collar. A standard issue drab or matching beige overseas cap was worn with this dress.

A wounded lieutenant of the 506th PIR, 101st Airborne Division is helped ashore from an LST at Southampton, England, on 9 June 1944. At left, a trench-coated lieutenant carries his web belt, complete with the canvas scabbard for a folding-stock M1A1 carbine. The black medic wears the issue raincoat.

Again, note the white 'playing card suit' tactical marking on the sides of the injured officer's helmet - a common practice in the Airborne, to distinguish regiments and sub-units. All officers were to have their rank painted or mounted on the helmet front, like these two lieutenants; after D-Day this was commonly ignored by front-line leaders. Helmet nets of various types were issued throughout the ETO, with finer-mesh examples used from late 1944; elasticated helmet bands were to be seen in 1945.

The ANC was an auxiliary organisation originating in the Spanish-American War. These nurses were essentially contracted medical professionals who were, like the WAAC, finally given full Army status in 1943/44. They started the war wearing a dark blue tunic and skirl service uniform. Their working outfit was the classic white dress with nurse's cap and blue wool cape with red lining. They also used a seersucker white and brown striped work dress with insignia. In 1944 the ANC converted to the standard WAC uniforms available at that date. Standard officer insignia were worn, with a branch emblem of a brass caduceus with a superimposed black 'N'; most nurses were second lieutenants, but were paid less than their male Army counterparts. Nurses had a plain beige off-duty dress - this was in fact copied by the WAC (see above). The front of the nurse's service dress hat was similar to the WAC 'Hobby' hat, but the back was rounded to the crown.

A corps consisted of a minimum of two divisions. In the order of battle of the US Army in the ETO in 1945 we find about 18 corps - the uncertainty over the exact number lying in the presence of a number of divisions under direct command of an army. Most of these corps had three divisions, some four, one five and one - XVI Corps of 15th Army- had six. A representative example is Gen Walker's XX Corps of 3rd Army, which comprised four divisions - the 4th and 6th Armored, and 76th and 80th Infantry. In addition a corps normally had many independent units of tanks, artillery, engineers and other specialists under direct command.

An army was formed from two or more corps. Ten armies were formed for service in World War II. The 2nd and 4th Armies were stationed in the US and consisted of divisions under formation. By 1945 the last of the divisional units based in the US had left these two armies and were headed for the front. The 1st, 3rd and 9th Armies served in France, Belgium and Germany. The 7th Army served in Sicily, the South of France and Germany. The 5th Army was stationed in Italy. The 6th and 8th Armies served in the Pacific, with the 10th formed on Okinawa. As an example, in 1945 Gen Hodges' 1st Army consisted of III, V, VII and XVIII (Airborne Corps) and totalled 17 divisions.

Army groups were formed with a minimum of two armies. In 1945 the Twelfth Army Group (Gen Omar Bradley) consisted of the 1st and 3rd Armies (Gens Hodges and Patton). The US 9th Army (Gen Simpson) was traded back and forth between the Twelfth and the British/Canadian Twenty-First Army Group (Gen Montgomery). The Sixth Army Group (Gen Jacob Devers) consisted of the 7th Army (Gen Patch) and 1st French Army (Gen de Lattre). The Fifteenth Army Group (Gen Mark Clark) was made up of the 5th Army (Gen Truscott) plus all the other Allied forces in Italy. In the Pacific, Army units served under Theater Commanders (Gen Douglas MacArthur and Adm Chester Nimitz). Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) commanded all ground forces in Europe (Gen Dwight Eisenhower).

England, 1944: HM Queen Elizabeth with a WAC officer and senior NCO. The captain wears her bars on the left front of the gold-piped WAC officer's overseas cap and on her tunic epaulettes, the Athena branch insignia, and the ribbons of the ETO and WAC medals. The first sergeant wears the generic ETO shoulder patch, and a year's worth of overseas service bars. (See also Plate D1.) Note the strong contrast between the dark officer's and lighter enlisted ranks' tunics.

In World War 1 entire divisions were withdrawn from combat for periodic rest and rebuilding. In the Pacific in World War II the short, violent battles for island groups and the time lag between invasions helped accomplish this rest cycle for Marine and some Army units. In the Mediterranean, Sicily fell in 30 days and the preparations for the Salerno and Anzio landings gave 5th Army units a reasonable chance to rest. In the ETO, and later in Italy, this cycling of units for rest was the exception.

Once a division was committed into combat, it was expected to stay at the front. During the war the 1st Infantry Division spent 442 days in combat, of which 317 days were served in the ETO. In France and Germany alone the 'Big Red One' lost 206 per cent of its strength to casualties; 85-90 per cent of this loss was from the three infantry regiments. During the 2nd Infantry Division's 314 clays of ETO service it lost 184 per cent of its strength. Among those infantry divisions which entered combat in Normandy and fought through the eleven months to VE-Day, the average loss was about 200 per cent of establishment.

This rate of casualties had a terribly wearing effect on units, and gave the ever-dwindling handful of old hands an even more fatalistic view of their fate than usual. As the war dragged on it seemed that only a 'million dollar wound' was going to get a GI out of the war with all his limbs. The exception was the Airborne force (82nd and 101st Divisions). They did suffer severe losses, and were kept in the line for longer than they should have been after D-Dav, but they were pulled out of the line to keep them available for future airborne operations.

The giant olive drab machine needed a constant flow of additional troops to keep up its strength. The AEF in World War I solved this problem by disbanding about every fourth division arriving in France and redistributing its men. In World War II the Army refused to allow this, and depended on individuals sent from the US to fill the gaps. Emphasising its machine-like viewpoint, the Army called these men 'replacements'. In 1944 the number of men individually trained for posting as replacement parts rapidly fell short of the needs of the ravenous armies in France. The units based in the USA were soon mercilessly plundered. This weakened these training units, and sent bewildered replacements forward to units with which they had no connection. The semi- trained (Us lurched through the system until they arrived at forward replacement depots, called 'Repple-Depples'. Here combat- experienced GIs, sent forward again after recovering from wounds, mingled with the green replacements for days or even weeks as they awaited new assignments.

Metz, late November 1944: riflemen and a BAR gunner from the 5th Division check houses for enemy 'stay-behinds'. Notice that only one wears a pack (to which he has strapped a K-ration box) and the others have their blankets, raincoats or ponchos stuffed through the back of their belts. The Germans turned Metz into a fortress which held up the Allied advance for many weeks; it finally fell to XX Corps of Gen Patton's 3rd Army on 22 November after a fortnight's hard fighting. At that time MajGen Walton Walker's XX Corps consisted of MajGen Stafford Irwin's 5th Infantry Division, the 90th Infantry Division, the 7th Armored Division, and the 2nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Group; but divisions were often switched between corps at short notice, and by the following spring XX Corps' composition was entirely different.

The 'savvy' veterans wanted to return to their old units, and commonly went AWOL (Absent Without Leave) to hitch a ride forward - whereupon their old outfits looked the other way and gladly took them in. The fresh replacements were ushered in small groups to their new units, usually in the front line and in the dark. Friendless and almost untrained in surviving this deadly environment, they were killed and wounded in droves, often still anonymous to the GIs of their platoons. In historian Stephen Ambrose's Citizen Soldier he says of the 'reppledepple' system: 'Had the Germans been given a free hand to devise a replacement system for the ETO, one that would do the Americans most harm and least good, they could not have done a better job.' General Norman Cota, who distinguished himself in combat as second-in- command of the 29th Division on Omaha beach, considered it both foolish and downright cruel to send a green young man into action in this way, robbed of the psychological support of buddies he had trained with and leaders he knew.

The authorities slowly realised the brutal and wasteful nature of the system, but did little to improve it beyond changing the name 'replacements' to 'reinforcements'. Some divisions took it on themselves to introduce reforms, however; they began holding replacements back after their arrival for (re)training by veteran NCOs. These men were then hopefully introduced to their new units out of the front line, with a chance to get to know, and be known by, their leaders and comrades. These replacements had a much higher survival rate and more quickly became assets to their units.

In MAA 347 we mention the 10,000-odd African-American soldiers of non-combat units who volunteered for infantry service in response to Gen Eisenhower's call during the manpower crisis of winter 1944/45. Other classes of recent civilians and soldiers were also rushed forward to swell the ranks of the rifle companies, including deferred college men (ASTP), surplus air cadets, and GIs stripped out of anti-aircraft, tank destroyer, and other support units. These were intelligent and sometimes seasoned men, making the quality of replacements received at the end of the war surprisingly superior.

January 1945: a 'lost patrol' of the 94th Division pose for a photo, happy to be back in the fold and getting canned rations. Both Parsons and M1943 field jackets can be seen, and note the 94th's patch worn by the medical tech-corporal at right foreground. At left centre, the BAR man's weapon still has its bipod (often discarded), and he carries the cleaning kit on his belt. Peering over his shoulder is a dark-bearded veteran; the smooth-faced boy at extreme left is probably a more recent replacement.

Historically, Americans have been a technically minded people. As early as the 1840s the 'flying artillery' of the Mexican War earned a high reputation, and at most periods, including World War II, the artillery has been the most effective branch in the US Army. The artillery suffered far fewer casualties than the infantry, and this contributed to its level of professionalism and cohesion. The quality of its mostly redesigned and sometimes motorised guns was about average for the period, but US-developed fire control and ammunition made all the difference.

Ammunition was first rate and usually in good supply. By German standards, US employment of artillery was lavish. In part due to its availability, US leaders were much more willing to expend ammunition than men. The introduction of air-bursting VT (radar) ammunition in late 1944 made the US guns even more deadly. With the use of Forward Observers, light spotter aircraft and telephone/radio communications to tie them together at a Fire Direction Center (FDC) they had unequalled potential to co-ordinate their fires, creating a specially devastating 'Time on Target' (ToT) technique. ToT was executed by mathematically co-ordinating different guns at different locations to land their shells on target at exactly the same moment. The FDC's accuracy and speed in calculating the complex mathematics was aided by a US-developed artillery Graphical Firing Table (GFT) slide rule.

March 1945: crossing the Rhine in a DUKW, a lieutenant from an amphibious unit glances back at GIs of the 89th Division. Many seem to be wearing the new two-part M1944 pack system (see Plate G2).

The war began with the Army using both the old French 75mm howitzer and the newer M5 Sin (75mm) gun. By 1943 the 75mm was rapidly disappearing from all but anti-tank work. The M2 105mm howitzer soon became the most common US artillery piece of the war. It had a range of 12,200 yards (11km, 7 miles) and used high explosive (HE), white phosphorus (WP) and smoke ammunition. The towed gun with shield weighed about 2.5 tons; the 75mm and 105mm shared the same carriage. The 105mm was also mounted as the M7 Priest self-propelled gun, based on an M3 Grant tank hull and weighing about 25 tons. The M7 had a seven-man crew and was also armed with a .50cal machine gun in a kind of forward 'pulpit' - thus its name. It was first issued in 1942 and over 3,000 were ultimately built.

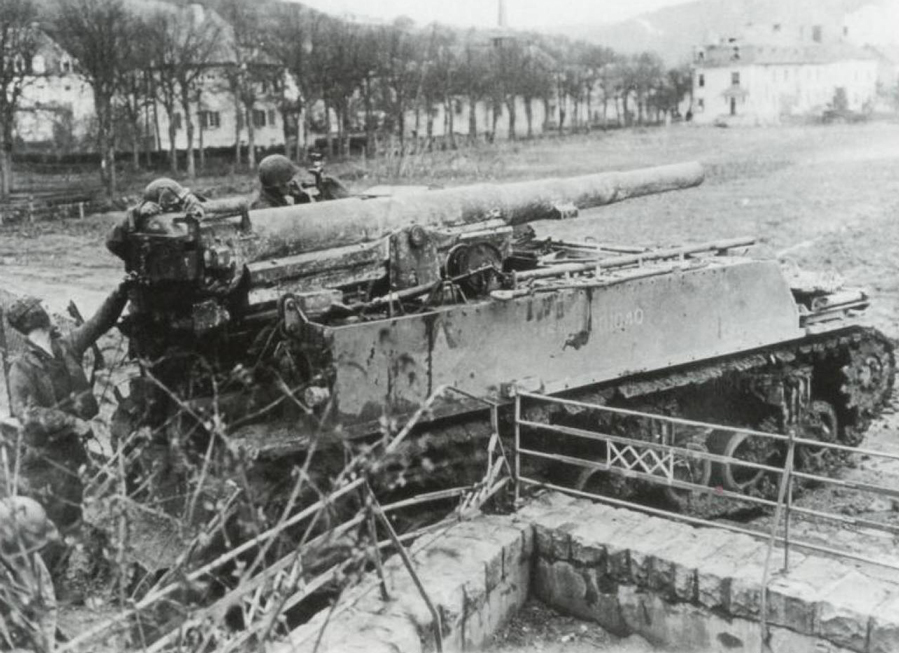

Luxembourg, February 1945: a gunner checks the angle on the barrel of his M12 155mm self-propelled howitzer. These guns were sometimes used, as here, in the direct fire role during serious street and fortress fighting; the effect was devastating.

The 75mm pack howitzer was developed after World War I as a light field piece that could be broken down and 'packed' by six mules in rough terrain; it was also modified as a horse-drawn weapon. By Work! War II the 1.1-ton M3 pack howitzer was issued to infantry units to fill out their cannon companies, in which role it was commonly used in the Pacific. An airborne M8 version weighing 1,300lbs (590kg) was parachuted or glidered in for use by the artillery units of the airborne divisions; A larger 105mm pack howitzer weighing 1.3 tons was available by 1944; its accuracy left something to be desired and at 8,300 yards (7.6km, 4.7 miles) its range fell about 1,000 yards short of that of the 75mm. Used in the Pacific, Italy and in airborne operations, the little pack guns did yeoman service.

Based on the French 155mm GPF gun, the 155mm gun/howitzer also proved a very successful weapon system. (Note that both the 155mm and 8in artillery pieces came in different 'howitzer' and longer-barrelled, longer-ranging 'gun' versions.) The new M1 155mm howitzer weighed 6.4 tons and its HE, WP and smoke shells had a range of 16,300 yards (14.9km, 9.2 miles). The longer-barrelled M1 155mm gun weighed 15 tons and could fire HE and AP shells over 25,000 yards (22.8km, 14.2 miles). Some of the older M1918A1 155mm guns were mounted on M3 Grant hulls as M12 self-propelled artillery. After limited use in North Africa, six battalions were belatedly fielded in Normandy. It was guessed that the guns would be useful for direct fire operations against fortifications, and indeed they made short work of all but the stoutest, as well as providing general indirect fire support.

Due to availability of British ammunition a 4.5in gun was also built to supplement the 155mm; this was slightly heavier than the 155mm howitzer at 6.6 tons, and its 551b ammunition did not have the hitting power of the 155mm's 951b shell. The heavy 8in howitzer shared the 155mm's gun carriage, weighed about 15 tons and had a range of 18,500 yards (16.8km, 10.5 miles). Independed corps artillery battalions were usually armed with 155mm ('Long Tom'), 4.5in and 8in pieces.

Under camouflage netting, gunners of an African-American artillery unit man the standard M2 105mm howitzer during a fire mission; note the locally-cut timber under the wheels. Nine independent black artillery units served in France and Germany, of which the 969th FA Bn (Colored), an VIII Corps outfit equipped with M1A1 155mm howitzers, won a Distinguished Unit Citation for its defence of Bastogne.

The 'siege gun' version of the 8in gun weighed 35 tons; used by both the US Navy and Army, it fired shells weighing over 2001bs (90.7kg) to ranges of up to 35,000 yards (32km, 19.8 miles). The GIs learned that if they drilled a small hole through the shell fuze it caused a satisfying screaming sound as the round went down range. The 240mm howitzer weighed 32 tons and could fire its 3601b (163kg) HE round 25,200 yards (22.8km, 14 miles). Both the 240mm howitzer and the 8in gun used a wheelless split trail carriage. They were employed for the first time in the defence of Anzio; these weapons were later transferred to France for use against the fortified port cities.

Mindful of the success of the Russians and Germans in deploying rocket-propelled artillery', the US also fielded rockets in late 1944. The 4.5in finned rocket was used with limited success in saturation bombardment missions. The rockets were mounted on truck beds or on the turrets of some unhappy Sherman tanks (model T34). As the rockets had a large launch signature, it was expedient for rocket units to 'shoot and scoot'.

La Haye du Puits, Normandy, summer 1944: a heavy weapons team from the 79th Division bring up their 81mm mortar. The tube and the baseplate each weighed 45lbs (20kg), and the GIs use shoulder pads to cushion the load. In the left background one man wears the pannier-like ammo vest to carry rounds.

In 1939 production of the M3 37mm anti-tank gun began; this was generally based on the German 37mm, and over 20,000 were made in 1939-43. This drop-breach gun weighed just over 9001bs (408kg) and was used both as an AT gun and in the M3/M5 Stuart tank series; it could fire HE, AP, and a very useful canister ('grapeshot') round. The 37mm was adequate for use against Japanese tanks, but by the time of its deployment against the Germans in Tunisia it was ineffective. By 1944 the 37mm was only to be seen in the Pacific and in US light tanks.

The need for a heavier AT gun led to US production of the current British 6-pounder (57mm). The US M1 57mm weighed 2,700 lbs (1225kg) and fired AP or HE rounds, and was known for its vicious recoil. Some 16,000 had been made when production ceased in 1944; although it continued in service throughout the war it was obsolete for AT work by that date.

July 1944: in the wrecked streets of St L6, Normandy, GIs unhitch a 57mm anti-tank gun from a halftrack smothered in their slung packs. This US version of the British 6-pdr AT gun was barely adequate by 1944 standards but was used for lack of anything better.

The M5 3in (75mm) artillery piece was used for anti-tank work with good results in Tunisia. With a redesigned gunshield this 2.5-ton piece gave effective service until VE-Day. The M2 90mm AT gun used in the M36 tank destroyer and M26 tank was also built as a split-trail towed AT gun, but none reached combat before VE-Day.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com