MARK R. HENRY, MIKE CHAPPELL

THE US ARMY IN WORLD WAR II. THE PACIFIC

The US Army of 1939 had no flamethrowers, but they were quickly developed by the Chemical Corps and issued to the combat engineers. The first model (E1-R1) came into use in 1942 in New Guinea but proved very weak and unreliable: '... Cpl Tirrell crawled through the underbrush to a spot some 30 feet from a Japanese emplacement. He stepped into the open and fired his flamethrower. The flaming oil dribbled 15 feet or so, setting the grass on fire. Again and again Tirrell tried to reach the bunker, but the flame would not carry. Finally a Japanese bullet glanced off his helmet, knocking him unconscious.' Poor design, fragility of fittings and the heat and humidity of the Pacific were hard on the E1-R1 and M1 models. The use of gasoline also caused projection problems. Dogged attempts to improve it paid off in the steadily more reliable M1A1 (1943) and M2 (1944) models.

In 1942 just 24 flamethrowers were assigned to a division; by 1944 they had become a key weapon in the Pacific, and the divisional scale of issue had reached 192. The successful M1A1 and M2 used one cylinder of propellant nitrogen and two cylinders of 'napalm' - jellied gasoline, with an improved range of 40-50 yards. The M1 and M1A1 flamethrowers weighed about 701bs (31.7kg), and their 5gal fuel capacity gave all models only eight to ten seconds of fire. An assistant accompanied the flamethrower operator to turn on the tanks from the rear just before use; by 1944 the assistant was to carry a jerrycan of additional fuel. The E1, M1 and M1A1 had electrical spark ignition problems, so some teams carried WT/thermite grenades to insure that the target 'cooked off'. The M2 had a range of 50 yards and an improved pyro ignition system based on a Japanese method. Stuart and Sherman flamethrower tanks were also to be seen in the Pacific in 1944-45. (Flamethrowers were available in Europe, but not used in such numbers.)

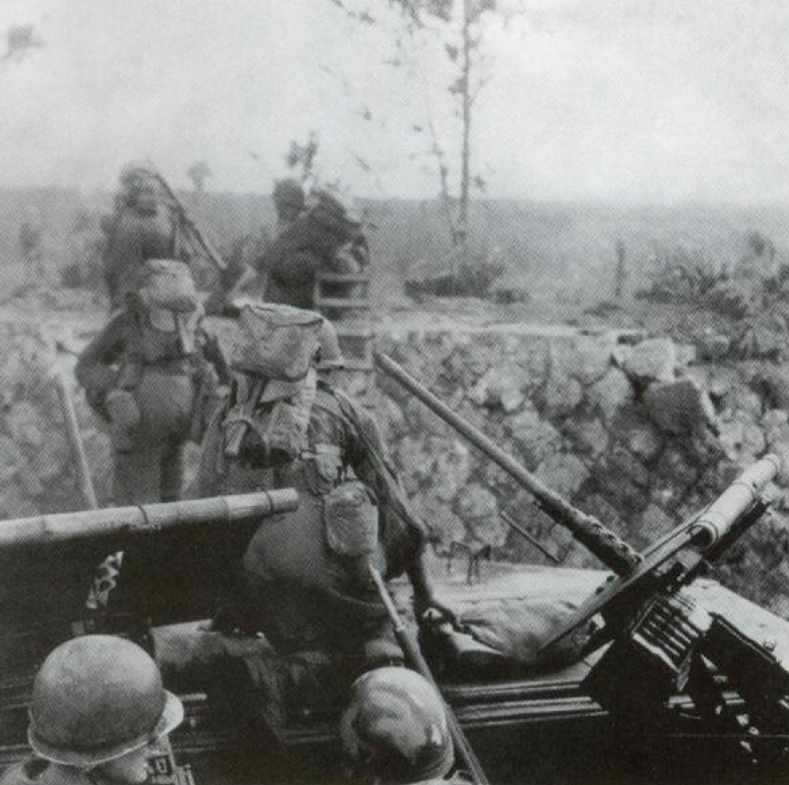

Lone flamethrowers deployed without protection were usually suppressed or destroyed with little impact. By 1944 many Army (and Marine) divisions were organising specially equipped bunker-busting teams of 15-25 men who used 'corkscrew and blowtorch' tactics. These teams were formed around two flamethrowers and included riflemen, BARs, demolitions men and bazookas. They used flamethrowers to burn off jungle cover to expose Japanese-held caves and log bunkers. Then riflemen, BARs and bazookas laid down suppressive fire as the flamethrowers approached. Flame shot across the gun slits forced the enemy back as the demolition teams closed; then combinations of thrown demolition charges, bazooka fire and close-range flame finished the job. Near the front lines, jeep-mounted refill/repair positions supported the still short-winded and fragile flamethrowers. These integrated teams proved highly successful, but not all divisions organised them.

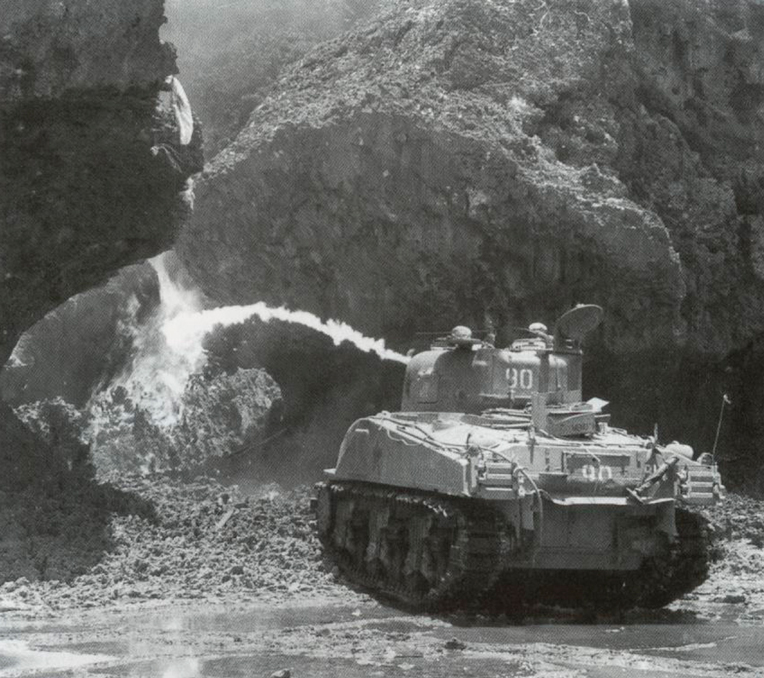

Okinawa, 1945: an M4 Sherman flame-tank ('Zippo') of the 713th Tank Bn hoses down a cave entrance in support of the 7th Division's advance. Shermans modified to take flamethrowers became available in mid-1944 and were heavily used on Okinawa; they could shoot flame up to 65 yards and sustain fire for about one minute. Although flame-tanks in the Pacific were quite widely dispersed in small numbers, the 713th was the only complete battalion.

In the Pacific, Mediterranean and North-West European theatres successful amphibious operations would prove critical to winning the war. Fortunately, in the 1930s the US Marine Corps - with very limited assistance from the Navy and Army - pursued doctrine and hardware to make these operations possible. A waterborne assault is among the most difficult manoeuvres an army can attempt. The costly failure of the British/Canadian 'raid in force' at Dieppe in 1942 foreshadowed disaster for any opposed amphibious landing. By 1943 the US was able to prove their amphibious equipment and doctrine to be sound and viable, and in the last two years of the war American strength and expertise in this challenging form of warfare became unsurpassable.

Bougainville, 1944: a 37th Division flamethrower man checks out a burned Japanese bunker. By 1944 the improved M1A1 and M2 flamethrowers had become a integral part of small unit tactics for neutralising Japanese positions - the so-called 'corkscrew and blowtorch' method. Operators sometimes 'hosed down' targets to soak them with fuel before lighting them up.

The standard landing craft of the war was the 'Higgins boat', designed by that company at the behest of the Marine Corps (over the objections of the US Navy). The Higgins boat or LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle/Personnel) in all its variants was said by Eisenhower to have been one of the three tools that won the war for the Allies (the others being the C-47 Dakota transport aircraft, and the jeep). This floating shoebox with a front ramp carried approximately 36 combat-loaded soldiers. More than 22,000 LCVPs were produced before VJ-Day.

Primary among the Army's amphibians was the six-wheeled DUKW (universally known as the 'duck', although the title code letters officially stood for '1942 - amphibious - all wheel drive - dual rear axle'). Essentially an amphibious 214-ton truck with a rudder and propeller for water travel, it could simply drive down into the water and then drive out again on the other side. Developed in 1940-41, it came into Army service in 1942. The DUKW could travel at 45mph on land and 6 knots in the water, carrying 25 men or 2.5 tons of supplies. It gained early fame for an incident off Cape Cod in 1942 when an '... Army truck rescues men from a stranded naval vessel'. The Allies rapidly became dependent on the logistical link it provided between ship and shore. In the Pacific, the Army operated several amphibious brigades of DUKWs; US Navy-crewed DUKWs also supported landings in the Mediterranean and Normandy.

Loading an amtrac; the LVT-4 of 1944 could hold about 34 passengers, and had a rear ramp, which made loading and unloading much easier and safer. Note the gull-winged track pattern. These men all carry the M1936 musette as a pack.

The Army also used the USMC-developed amphibious tractors or 'amtracs' to support their operations in the Pacific. This vehicle had been initially designed by John Roebling for civilian use as a 'swamp buggy'. The open-topped Landing Vehicle Tracked (LVT-1) or 'Alligator' was a fully-tracked amphibian that could cross reefs and sandbars to deliver troops on to the beach, propelled by its flanged track plates. With a crew of three, it carried 20-plus soldiers or 2 tons of cargo, and travelled at 25mph/4 knots; at least three machine guns could be mounted, but it was initially unarmoured, and was a transport rather than a fighting vehicle. The improved LVT-2 or 'Water Buffalo' which reached combat units in 1943 carried 24 men or 3 tons of cargo. Infantry had to clamber over the hull sides to disembark from the LVT-1 and -2; the LVT-4 (1944) and LVT-3 (1945) had rear ramps, and could carry a jeep and a 37mm gun, a 105mm gun, 4 tons of cargo, or at least 32 infantry.

Okinawa, 1 April 1945: over the top - GIs of the 96th Division clamber between the .50cals at the front of an amtrac and up a seawall at Hagushi beach. The 'April Fools Day' landing by four divisions was unopposed. These men wear the old M1928 packs; and note, centre foreground, a camouflage-painted helmet.

The 'amtracs' soon gave birth to 'amtanks', armed and lightly armoured variants to provide fire support at the point of landing (though their inherent vulnerability was always recognised, and every effort was made to get 'real' tanks ashore as early as possible). The LVT(A)-1 and -2 of 1944 mounted the 37mm gun turret from the Stuart M5A1 light tank; the LVT(A)-4 had an open-topped turret with a short 75mm howitzer. Small numbers of amtracs were also modified to carry flamethrowers, rocket projectors, several .50cal machine guns and 37mm aircraft cannon. The armour on the LVT(A)s was only capable of turning small arms fire, but their presence on the beach gave troops a critical firepower edge during the first minutes of a landing.

The USMC enjoyed priority of issue, and the first US Army amtrac battalions did not see combat until the Kwajalein landing in the Marshall Islands in February 1944; each had 119 I.VTs organised in two 51-vehicle companies and a headquarters. In time the Army would actually outstrip the Marines in these units - 23 Army to 11 Marine amtrac, and seven Army to three Marine amtank battalions. By June 1944 in the Marianas the first Army amtank unit, the 708th Amphibian Tank Bn - which won a Distinguished Unit Citation on Saipan - had four companies each with 13 x LVT(A)-ls and 4 x (A)-4s, supporting the amtracs of the 534th, 715th and 773rd Amphibian Tractor Battalions.

The only US Army tanks available in the Pacific at the time of Pearl Harbor were about a hundred M3 Stuart light tanks of the Provisional Tank Group (192nd and 194th Tank Bus), on Luzon in the Philippines. Although the M3 was under-gunned and under-armoured by international standards, the unit fought bravely and effectively against the even weaker Japanese Type 95s before the fall of Bataan.

New Guinea, April 1944: M4A1 Shermans and infantry prepare for an assault up Pancake Hill, Hollandia. The GIs have fully loaded camouflage jungle packs; the tank crews wear both leather tanker and M1 steel helmets. At night the tanks would 'laager up' side by side, facing in opposite directions, to fend off any surprise attack.

By 1943 the heavier M4 Sherman began to become available, but until 1945 the improved M5A1 Stuart still equipped some companies of mixed tank battalions. The units in theatre represented about one-third of the US Army's total of tank battalions; none were organic to Army divisions in the Pacific - all were independent, assigned by corps or army as needed.

For the first half of the war the jungles and islands did not provide much of a field of use for the tank; and throughout the war its main role was in direct support of infantry, where its cannon and machine guns were of huge value in suppressing enemy fire and 'bunker busting'. Stuarts were fitted with flamethrowers in 1943; and the flamethrower-equipped Shermans of the complete 713th Tank Bn were particularly valuable in 1945 on Okinawa, where the bloody fighting sometimes resembled World War I trench warfare. Apart from the fighting on Luzon in December 1944-February 1945 tank-vs-tank actions were rare, and the US equipment was always superior to the Japanese. (On Peleliu in September 1944 US Marine Sherman crews used HF. rounds to ensure a kill when they encountered Japanese Type 95s - the armour-piercing rounds punched right through them so easily that they failed to destroy them.)

PACIFIC THEATRE CAMPAIGN SUMMARY

While the main purpose of this book is to describe uniforms and equipment, a brief campaign summary may help readers put this material in context.

Leyte, 1944: these men use the packboards usually associated with mountain troops to carry gear through the jungle. The foreground GI appears to be hauling the special rubberised case for carrying electronics and other water-sensitive gear.

The Japanese began amphibious landings on the islands culminating in the 22 December 1941 landing on Luzon. The half-trained Filipino army rapidly retreated and Manila fell on 26 December. Gen Douglas MacArthur made a planned withdrawal to the defence of the Bataan peninsula. The combined Filipino/US defenders were slowly pushed back and finally forced to surrender on 9 April 1942. The fortified island of Corregidor held out until Japanese amphibious assaults forced surrender on 6 May. MacArthur had failed to properly victual Bataan and Corregidor, but the defence had cost the Japanese five precious months.

In the winter of 1942 the Australian 7th and US 32nd Divisions, fighting in some of the worst jungle terrain in the world, forced the Japanese back from Port Moresby and into the defence of Buna. With almost no armour or artillery, the Allies finally seized Buna in January 1943. The US lost 60% of their force to disease along with 2,700 battle casualties. After a year of lighting, enveloping US amphibious landings at Aitape/Hollandia in April 1944 defeated the Japanese 18th Army at a cost of just 5,000 men. The US 41st Division's capture of Biak island in June 1944 was among the last pitched battles of the campaign. Skillful combined Australian/US operations would continue in New Guinea until its final subjugation in August 1944.

Japan, 1945: soldiers of the 'Americal' Division - note shoulder patch worn on khakis by the lieutenant, far right - receive medals before they return to the States. The men wear HBTs and helmet liners; NCO stripes began to reappear after VJ-Day.

The US Army joined the Marines in the battle for Guadalcanal in October 1942 with the deployment of the 23rd Division. By January 1943 the 25th Division along with the 2nd Marine and 23rd Divisions were on the offensive; by February the island was secure, for the loss of 6,000 US casualties and an additional 9,000 sick.

The Army landed on New Georgia in July 1943 with the 37th and 43rd Divisions; joined by the 25th Division, they overcame fierce resistance and secured the island by the end of August.

In November 1943, Marines seized a five-by-ten mile perimeter around Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville. Defence of the newly won terrain was left to the 23rd and 37th Divisions. By mid-1944 the island was secured.

With the strategic Rabaul at the north end of the island, the 1st Cavalry Division and US Marines landed at the south (Cape Gloucester) in December 1943. By March 1944 the 40th and 1st Marine Divisions had advanced up the coasts, but this had cost MacArthur over 2,000 casualties for little real gain. The Australians then took over and contained Rabaul. The 1st Cavalry Division had gone on to capture Los Negros island (Admiralties) in late February 44.

Okinawa, 1945: a rare capture of a Japanese soldier. This GI has a 'WP' grenade hanging from his M1936 suspenders; his helmet chinstrap is tucked up into the issue elastic neoprene band. Interestingly, he has three wristwatches on his left arm.

After receiving desert training, the 7th Division landed on the cold, wet Japanese-held island of Attn in May 1943. Rooting out the 2,500-man enemy garrison cost the 7th 1,700 battle casualties and 2,100 men to non-battle causes, especially trench foot. The Japanese finished the battle with banzai charges and only 29 men survived the fighting to be captured. A combined US/Canadian force (including the 1st Special Service Brigade) landed on nearby Kiska island in August 1943, to find that the 4,500-strong Japanese garrison had been evacuated in late July.

Philippines, early 1942: an American officer in khaki chinos, with an M1928 Thompson, standing next to his Filipino counterpart. Both wear the M1917A1 helmet with web chinstrap; the Filipino officer wears medic's yoke suspenders, and a revolver in a civilian holster. US officers commonly served in the newly formed Filipino units. See Plate A.

The 27th Division seized Makin (Gilberts) in November 1943. In February 1944 the 7th Division landed on Kwajalein (Marshalls), seizing the island in a week for a loss of just under 1,000 men. Later in the month, the 27th Division landed on Eniwetok in support of the Marines with similar results. In June 1944 the 27th Division reinforced two Marine divisions in the bitter fighting for Saipan (Marianas). Almost 30 days of fanatical Japanese resistance ended on 13 July; US losses were 16,000 men. During the battle, the 27th's commander was relieved by the (Marine) corps commander for lack of aggressiveness - a conflict which probably had more to do with differences in tactics between the Army and Marines than anything else. Guam (Marianas) fell to the Marines and the 77th Division in July 1944.

Okinawa, 1945: three GIs from the 77th Division wearing typical uniforms and equipment of late war front line infantry. The medic (centre) has the standard medical pouches but not the yoke suspenders. Note (left) the World War I canteen, and the three-pocket grenade pouch hanging in front of his thigh. Both riflemen appear to be wearing the old M1928 pack, with two of the suspender straps looped together across their chests. At (right) the deep pocket of the second pattern HBT shirt shows well.

The 1st Marine and 81st Divisions made the preliminary landings on the Palaus (Peleliu) in September 1944; fierce fighting cost the Marines 6,500 and the 81st 3,300 men. MacArthur's first landings in the Philippines hit Leyte unopposed in October. The Japanese rapidly fed in reinforcements, and the capture and pacification of the island would continue until VJ-Day, costing some 16,000 US casualties. MacArthur then landed on Luzon in January 1945. Gathering strength, the Army slowly began the drive to Manila and the nearby Clark Field airbase. The 275,000 Japanese troops commanded by the able Gen Yamashita mostly stayed in the rugged terrain of the north, waiting for a battle of attrition. Racing ahead with the 1st Cavalry and 37th Divisions, the US forces seized Clark Field and Manila after hard fighting, especially in the city; Manila fell on 4 March 1945. Corregidor would fall to a daring airborne and amphibious assault on 27 February. Until VJ-Day MacArthur continued to expend his forces on reducing the Japanese on the various islands of the Philippines archipelago and preparing for the assault on Japan. US losses in the Philippines were 64,000, with an additional 100,000-plus non-battle casualties.

This unusual photo of the commander and staff of the 6th Ranger Bn in a rear area shows rank insignia and camouflage helmet covers being worn. In combat no rank would be displayed, and billed soft caps were preferred by the Rangers. The CO (front) appears to be wearing paratrooper boots. The 6th Rangers were constituted in 1944 and served with distinction in the Philippines.

World War II saw huge advances in the treatment and evacuation of casualties, especially by US medical personnel. 'Wonder drugs' like penicillin, sulfa powder and morphine, and the ability to transfuse with stored blood, drastically reduced deaths due to infection and shock. Medics and sometimes GIs themselves carried sulfa powder and one-shot morphine ampules for immediate use in the foxhole. If a wounded GI could be safely evacuated for treatment - a big 'if' - his chances of survival were remarkably high, averaging 95.5% in 1941-45. About 75% even of stomach wounds, and an astonishing 95% of chest wounds, survived treatment. Even men with limbs blown off, or head wounds, survived more often than not - if they were evacuated to the rear areas quickly enough.

Burma, 1944: dog handlers of BrigGen Frank D.Merrill's 5307th Composite Unit ('Merrill's Marauders', later Mars Task Force) - cf Plate F. The GI with the carbine has padded the straps of his camouflage jungle pack. The Thompson gunner (left) wears the rubber and canvas jungle boots, and a soft billed cap under his helmet; note his dog's first aid pouch. For their third mission in April 1944 the 5307th comprised H Force (Col Hunter) with 1st Bn divided into Red and White Combat Teams, plus the Chinese 150th Regt; M Force (LtCol McGee) with 2nd Bn and 300 local Kachin guerrillas; and K Force (Col Kinnison) with 3rd Bn divided into Orange and Khaki Combat Teams, plus the Chinese 88th Regiment.

Disease, as always, was a major problem: during World War II as a whole, for every one man wounded in combat 27 were temporarily disabled by disease. In the Mediterranean and European theatres the Army's greatest single scourge was venereal disease. Malaria was also a serious problem in North Africa and Sicily. In the Pacific, VD was not a problem - but almost every other disease known to man was; the heavily jungled and malarial South-West Pacific was especially hazardous. Malaria was almost universal in combat areas, and dysentery, dengue fever and typhoid could cause debilitating fever and diarrhoea. For malaria the Allies produced Atabrine pills, which would suppress the symptoms; their side effects were that they turned the skin a yellowish hue - and were rumoured to cause sterility, which discouraged soldiers from taking them as ordered!

Okinawa, 1945: this veteran infantryman from the 96th Division is - typically - as lightly equipped for combat as possible. He has only his rifle, a cartridge belt, a first aid pouch and an (empty) canteen carrier visible; he might add a poncho and a grenade.

Wounds and serious diseases played a smaller part in the day-to-day miseries of the average GI than the results of the generally unhealthy environment. In the Pacific minor cuts, abrasions and insect bites rapidly became infected and often refused to heal without lengthy treatment. The chafing of constantly wet clothing caused widespread fungal skin diseases and ulcerations - generically called 'jungle rot'. Another medical problem not to be underestimated in the Pacific was simple heatstroke caused by high temperatures and extreme humidity.

As the Japanese gave priority to attacking aid stations and killing medics, the latter wore no red cross markings and commonly went armed. Aborigines in the South-West Pacific gave yeoman service in moving the wounded to the rear areas. Chaplains were also commonly to be found serving alongside medics.

Okinawa, May 1945: clustered round a jeep radio, weary GIs of the 77th Division - note marking on side of helmet, and see Plate G - hear the news of the German surrender. Against the rain they wear the poncho, with its 'turtleneck' drawstring closure - see Plate C. For the men of the 'forgotten armies' in the Far East the war is emphatically not over yet.

(In the European theatre German troops generally did not fire deliberately on medical personnel. It was thus in the interests of stretcher bearers and medics to be distinguished in combat by the wearing of the red cross armband, and red cross markings on white disks or other shapes on their helmets.)

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com