RICHARD BRZEZINSKI, ANGUS Mc BRIDE

POLISH ARMIES 1569-1696

A: Siege of Pskov, 1581

The Muscovite campaigns of Stefan Bathory (1579-82) were hindered by the bitter Russian weather. This scene is based on contemporary remarks that soldiers often froze to death, even on horseback. The Englishman Mundy, for example, saw: 'Horses' noses and men's beards hang dangling with icicles', and heard of: 'countrymen coming on sleds... frozen stiff stark dead, still holding the bridle or reins in their hands, standing or sitting as alive guiding their horses. Others have been brought in so on horseback, their stiff benumbed limbs keeping them fast in the saddle. A soldier standing sentinel with his musket on his rest hath been found in that posture, stark dead and stiff with cold. These are common reports'.

A1: Lithuanian infantryman

The Lithuanians at first had much in common with their Muscovite neighbours. They wore Muscovite-style long, padded kaftans with high collars, essential in the Lithuanian winters, which were matched in severity only by those of Muscovy. The quilting gave protection not only against the cold but also as a form of armour. King Bathory showed interest in such kaftans; in a letter of 1577 to the Livonian hetman he wrote: 'It was brought to our attention, that Your Honour, has had a silk kaftan made, which is proof even against bullets. We instruct Your Honour to send it to us most urgently, with the craftsmen who made it...' Lithuanians seem to have abandoned their Muscovite tenden¬cies in fashion by the beginning of the 17th century, and were afterwards dressed in similar manner to the Poles.

The figure here is based on Lithuanians in engravings by Adelhauser & Zündt (1567) and Vecellio (1590s). According to Vecellio, Lith¬uanians wore red hats lined in a different colour. His arquebus bag is reconstructed from early 17th-century Hungarian and Polish prints. Such bags were probably used by most soldiers (see also G1).

A2: Hussar Comrade, 1560-90

King Bathory brought with him several 'banners' of Hungarian hussars as part of his Guard when he arrived in Poland in 1576. Hussars were, however, already the predominant type of cavalry in Poland. The use of white and black bearskins is mentioned, for example in Orzelski's account of Bathory's entry into Cracow in 1576. The figure is based mainly on a woodcut in a book by Czahrowski (1598), and on hussars in De Bruyn's book of 1575 Diversum gentium amatura equestris. The gilded szyszak helmet is of the Hungarian style worn by wealthier hussars in the 16th century (MWP). Wings worn tacked onto curved wing-shape shields were the forerunners of the more stylised wing-shaped ornaments. Shields were carried by hussars until the 1570s, though many accounts speak of them still being in use well into the '80s and '90s.

A3: Hungarian Haiduk Officer, 1577

Bathory's Hungarian and Transylvanian haiduk guard came to Poland with him in 1576. They differed little in dress from the Poles, though because of the warmer Hungarian climate their clothes tended to be somewhat less substantial, and usually shorter in cut. This officer has an overgarment shorter than his undergarment, whereas the Pole's would usually be of equal length. Generally speaking the infantryman's dress was hopelessly inadequate: during the Pskov campaign, Piotrowski notes after the first snows: 'Fur-coats begin to fetch a good price... but with the poor infantryman in the earthworks, God only knows what will happen'.

The figure is based on Abraham de Bruyn's costume book of 1581. The dangerous-looking spiked buzdygan mace was once in the collection of Jan Strzalecki; it is very similar to the one being carried in de Bruyn's engraving. The sword is a Hungarian 'Batorówka'-type sabre, with character¬istic long quillons, named after King Bathory because of the picture of the king on the blade (MWP). Gloves are restored from an officer in the 'Pattern of Costumes' painting.

'Death and the nobleman', a stucco relief in Tarlów parish church, dated to shortly after 1640: perhaps the clearest existing illustration of the dress and equipment of an unarmoured Polish cavalryman. He wears typical Polish dress: zupan undergarment, kontusz overcoat, fur-lined kuczma cap with feather, and high leather boots. The whip, cap, haircut and lack of spurs are typical Tartar features copied widely in Poland. Note in particular the winder key for a wheellock firearm hanging from an ammunition pouch. (Polish Institute of Art, Warsaw)

Polish light cavalry, probably 'cossacks' (they are described in French sources as 'carabiniers'), from Grand Marshal Opaliński's banner under Choiński, clothed in red during the celebrated entry into Paris in 1645. Note the lark of bows and spears, and the method of slinging the carbines. Aquaforta by Stefano della Bella. (British Museum)

A4: Hungarian Haiduk, 1577

Based on de Bruyn's costume book Omnium poene gentium imagines... (1577). He wears the very characteristic pillbox-shaped magierka (Hungarian cap), with peak and side flaps folded down in the cold weather. These caps were usually made of felt or thick cloth in various designs; they were commonly black, though many other colours were used. His simple sleeveless cape is a type seen in pictures of Poles and Hungarians throughout the period and widely worn throughout the army. The jacket has the curious split skirt joined by braiding which seems to have been fashionable in the 1570s. His sword is the typical open-hiked Hungarian sabre carried widely in both Hungary and Poland.

Bathory's footguard is described by Orzelski in 1576 during Bathory's arrival in Cracow as 'composed of Haiduks, Hungarians, Poles, and Circassians. They had long firearms, curved sabres, axes that were easy to throw; the age of all was young, their stature enormous; they were dressed in a violet colour'. Bathory's Hungarian haiduks differed slightly from Polish haiduks in that they were formed into regiments of between 500 and 3,000 men, which in turn were divided into rotas of 100 men; Polish haiduks do not appear to have used such large permanent groupings. These men earned a fearful reputation in Poland, for both their efficiency and their cruelty, especially among the Polish nobility who were frightened that Bathory would use them to impose a more absolute form of government. After Bathory's death many Hun¬garians stayed on in the Royal Guard to serve King Sigismund.

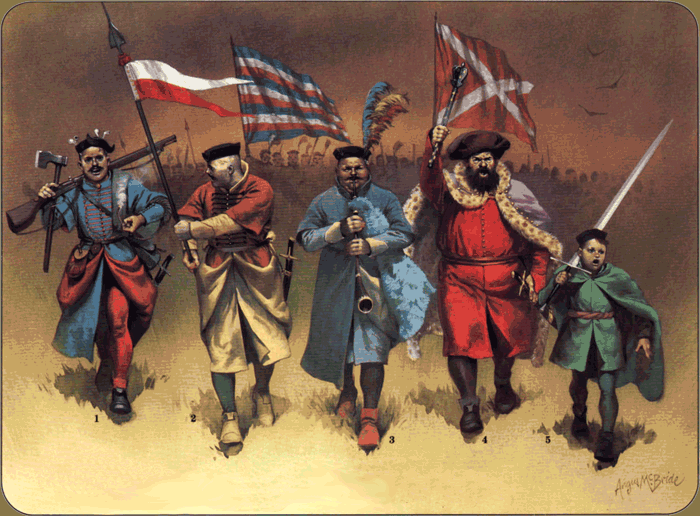

B: Ceremonial Entry of Queen Constantia; Cracow, 1605

The ceremonial entry into Cracow of the Austrian Archduchess Constantia, married by proxy to King Sigismund III of Poland, took place on 4 December 1605. It was normal in Poland to welcome foreign queens with magnificent processions in which the entire Royal Guard and numerous detachments from the nobles' private armies took part in full parade dress. The figures here are based on the famous 'Constantia Roll'.

B1: Rotamaster of Hussars, 1605

The rotmistrz ('rotamaster' or captain) was the commander of a Polish cavalry troop or infantry company. He carries a buzdygan mace, symbol of his rank. He wears a red silk zupan coat, and a black furred Hungarian cap, decorated with crane or heron feathers. His swords are a Tartar-style sabre worn at the waist and a Turkish-style koncerz, gilded and encrusted with turquoises. He wears a single 'wing' attached to the left side of the back of the saddle, this being the most obvious place for feathered decorations after the abandonment of the wing-shaped shield also usually carried on the left side.

His Turkish parade horse is dyed half red, an Eastern fashion which aroused incredulous com¬ments from Western observers. The English traveller Fynes Morison, in his Itinerary in 1598, noted that in Poland, 'They have a strange custom, seeming to me ridiculous, because it is contrary to nature... they paint their [horses'] manes, tails and the very bottoms of their bellies most subject to dirt, with a carnation colour which nature never gave to any horse...' During a similar procession of Poles into Paris in 1645 Mme. Motteville had to admit that the fashion, 'though fantastic, was not thought unpleasing'. The pale brick-red dye was obtained from the Brasil tree, and, curiously, was guaranteed by its manufacturers to be permanent and non¬toxic. The treament seems to have been reserved for light-coloured horses, though in India and Turkey darker horses were also dyed with henna. There here are, in fact, even references to horses in Poland being dyed green!

B2: Hussar 'Comrade' 1605

This figure is taken from a unit on the Gonstantia Roll, described on a caption as the 'Royal Troop'. However, it is possible that each separate rank of this unit was based on the dress of a different hussar 'banner' that took part in the ceremony. One contemporary description of the occasion records men in the hussar 'banner' of the Castellan of Czchów, Mikolaj Spytek Ligęza, wearing red welensy (capes to cover armour) on which were stars and crescents, so an identification with this 'banner' seems most likely. Note that stars and crescents are common Eastern European motifs in this period. They also appear on wings, flags, mailshirts, and bowcases (see D2).

He carries a Hungarian-style sabre, and under his leg an Italian-Hungarian style pallasz broad¬sword, a variety common to the hussars and used after the lance had been broken. The stirrups are of so-called 'Polish' type, though they owe a great deal to early Tartar models. Spurs are of the long-necked type with eight spikes, used until about the middle of the 17th century. The szyszak helmet is restored from an early German model of approximately similar form to the one on the roll (Wawel, Cracow). The comrade wears an anima-type breastplate with mail skirt and sleeves. Con¬temporary accounts speak of 'iron sleeves' worn with anima cuirasses, but it is not certain if this refers to separate mail sleeves, or to part of a mail shirt or to armguards. In any event, anima cuirasses of this type surviving in the Graz Armoury have separate mail skirts.

C: Polish Haiduks, 1660-25

Haiduks were the standard type of infantry in Poland over the period 1569-1633, and possibly even earlier. Uniformity of dress within infantry units started early in Eastern Europe - in Poland, certainly as early as 1557, and by the 1570s it was quite exceptional to find haiduks without uniform. On raising the unit an allowance was usually made for cloth for uniforms (barwa). NCOs and officers were usually dressed in good-quality English or Dutch woollen cloth, while the men had to settle for home-produced products. The most popular colour by far was blue in various shades, sometimes lined in red or white. Private units were dressed more or less at the whim of the commander, which usually meant in the colours of his personal badge or of the district where the men were raised.

Haiduks and Polish light-armed cavalry attack the Swedish lines at Kircholm. The haiduks are in blocks made up of several companies, and fire from the front rank of the formation; they are all dressed in blue uniform with red trousers, black caps and shoes. The light cavalry are armed with lances, and wear curious baggy caps and shaggy wolfskins, with no uniformity in colours of dress. From the 'Battle of Kircholm' painting. (Château de Sassenage)

The various types of infantry in Polish service, from a costume book by Abraham de Bruyn (1540?-87), Habits de diverses nations... published in 1581 in Antwerp, copied with slight variations from his earlier work of 1577 published in Cologne. The work was based on material supplied to de Bruyn by friends, and in his own words 'not yet known by the art of engraving or publishing'.

C1: Haiduk Arquebusier

This haiduk is based closely on the 'Patterns of Costume' painting from c. 1600-25. He is armed with an arquebus, lighter than the musket which by this time was in use throughout the West but was not immediately adopted in Poland. Rather interest¬ingly, he has no bandolier of measured charges over his shoulder. Indeed, not a single picture of Polish haiduks in this period shows bandoliers, and it seems likely that they were not used in conjunction with the arquebus. On his arm he carries a carefully wound match; over his shoulder, a canvas bag for his arquebus; and at his waist a leather bullet-pouch and a cuir-bouilli powder flask, of gourd shape with a fiat back and fluted belly. He wears a Hungarian sabre at his waist. The typical skin-tight trousers were worn by most Poles in this period. His shoes are so-called trzewiki. The light axe, typical for haiduks, is not the famous berdish, which was of quite a different form and did not appear in large quantities until the middle of the 17th century.

C2: 'Tenth-man', Gostomski's Company, 1605

The haiduk company was organised along a decimal system, and most commonly into units of between 100 and 200 men. Each section of ten men was commanded by a non-commissioned officer (dzięsiętnik), who was equipped somewhat differ¬ently from the rest of his section. His uniform would often be in different colours (e.g. red lined with green rather than blue lined with red); and his chief armament was a darda, probably a general term for shafted weapons such as halberds, half-pikes and partisans. The odd looking partisan-spear being used here is taken from the Constantia Roll. Haiduk NCOs are often portrayed with a darda that looks more like a halberd. The haiduk formation drew up in ranks ten deep, so the 'tenth-man' could take his position either at front or rear. In actuality he probably changed his position depending on the tactical situation, controlling the lire of his men from the rear or second rank, and moving to the front if the formation was threatened by cavalry.

C3: Bagpiper, Stradom Town Guard, 1605

This figure is taken from a unit on the Constantia Roll, described on a caption as the Stradom Town Guard. Bagpipes, of course, were not peculiar to the Scottish Highlands; they were used widely through¬out 17th-century Europe. This particular set are, however, somewhat unusual. The bag is made from a goatskin dyed pale blue, while the pipes bear more than a passing resemblance to Alpine horns; and it is easy to speculate that the location of the town of Stradom in the foothills of the Polish Highlands had some influence on the design. Other musicians used in the haiduks included drummers and lifers.

C4: Rotamaster

There were no regulations governing the dress of rotamasters, and consequently they wore rich civilian dress. There were, however, several common features in officers' dress: the large fur cap appears in several sources depicting officers, while their men are dressed only in Hungarian felt caps. Officers were also more able to afford lavish fur- lined cloaks, worn usually on the shoulders, held in place by a decorative metal brooch or chain. The rotamaster was quite often mounted. (Based on a watercolour by Heidenreich, dated 1601-12.)

C5: Rotamaster's Boy

There are frequent references to rotamaster's boys on haiduk company rolls; they were allowed a small wage. This one is dressed in haiduk fashion, even down to the Tartar hairstyle. The figure is based on the same source as C4. The sword is a two-hander with the arms of Mikolaj Radziwill, Voivode of Wilno dated 1572 on the blade, now in the Museum fur Deutsche Geschichte in East Berlin. Several pictorial sources show the young servants of Polish officers carrying such swords, despite their very un-Eastern appearance.

D1: Light-armed cavalryman, first quarter of the 17th century

Based on the contemporary painting of the battle of Kircholm, this could represent the appearance of unarmoured 'cossacks', Tartars, or rear ranks of hussar formations. Wolfskin cloaks were more common than leopardskins, and were worn by 'comrades' as well as 'retainers'. One incident confirming the wearing of wolfskins occurred prior to the battle of Kircholm in 1605, when a Lithuanian hussar was captured in battle gear and wolfskin by the Swedes, and taken to the Swedish King Charles IX. Count Mansfeld, one of the more distinguished of the Swedish officers, reportedly said to Charles: 'If all the Poles are like this one, I do not doubt that they will stand and fight our army'.

Haiduks marching with an officer: a woodcut from Paprocki's book Herman (1578). Paprocki probably took part in the Danzig campaign of 1577-78. Note the long skirts of the Haiduks' delias, tucked into their waist belts. The officer is carrying a nadziak war hammer with striped haft, and has a typical fur cap. (PAN Library, Kórnik)

This praise infuriated Charles, who at once replied: 'Go dress yourself in a wolfskin, and you'll be just as frightening'. (Naruszcwicz, History of J. K. Chodkicwicz, 1781.)

The cap, reconstructed from the Kircholm painting, seems to have been influenced greatly by the Serbian deli's cap, as shown on contemporary sources (Codex Vindobonensis. c. 1590). It is well known that the Polish nobility tried to imitate Tartar fashions; this new piece of evidence would suggest that they also tried to imitate the Serbian deli.

D2: Polish 'Cossack' cavalry officer, 1600-25

The misiurka mail helmet was often replaced by a rather more comfortable, typically Polish fur cap derived from the Tartar kuczma, and worn both summer and winter. Such caps were widely worn on campaign by 'cossacks' as well as hussars: and most contemporary pictures of the battle of Vienna show cavalry in fur caps rather than metal helmets.

The figure is taken as closely as possible from the 'Patterns of Costumes' painting, which can in fact be dated largely from the equipment worn on this figure alone. He carries a wheel-lock bandolet carbine (reconstructed from an example in the Polish Army Museum) and the typical Oriental bowcase and early short quiver. The figure is very similar to an engraving in Abraham Boot's Fournael van der Legatie from 1627. His sword is very similar to a gilded eagle-head sabre belonging to Christian II, Elector of Saxony, from 1610, now in the Historical Museum, Dresden, and has been restored from this. The armguard on the left arm seems to be of a Western style. This also supports the dating of the picture to the early 17th century since the Oriental karvash armguard was - according to Bochenski - only gradually introduced in Poland over the first decades of the 17th century. The rich dress and lack of an armguard on the right would tend to suggest that this man is an officer Polish officers frequently rode into battle with their right forearm bared as a mark of command.

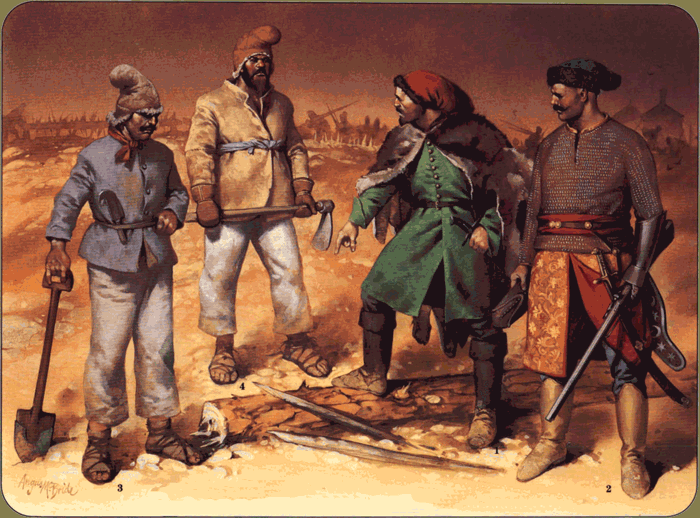

D3 & D4: Peasant infantry, 1630s

Based on watercolours added to one copy of Abraham Boot's Journael... (Gdansk Archives), these figures must give a fairly good idea of the appearance of ununiformed peasant levies, such as the Wybraniecka infantry, throughout much of the 17th century. They wear clothes made from sheepskins and homespun cloth and linen. They were rarely expected to take part in combat, and so were often specifically required not to have weapons or uniform. Tools and field-obstacles are added from the contemporary MS. of Naronowicz-Naroński's Military Architecture.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com