RICHARD BRZEZINSKI, ANGUS Mc BRIDE

POLISH ARMIES 1569-1696

Although Poland's recent problems have captured the imagination of the Western world, few people will realise that at one time the Polish state was one of Europe's great powers. One of the chief instruments of her success was undoubtedly her army, which though small can claim many accomplishments and major successes in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Many will know of King John Sobieski, whose legendary 'winged' hussars saved Vienna from the menace of the lurks, but little concrete material has ever been published in the English language on the army that achieved this and other equally remarkable feats.

Who, for instance, has heard that a Polish army once took Moscow and placed a Polish Tzar on the Muscovite throne? For a long time the balance of power between Poland and Muscovy could have tilted either way. and it was only by chance that Muscovy rather than Poland 'gathered up the Russias' to become the great Eastern European power. Who realises that one of the world's great commanders, the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus, spent most of his military career fighting the Poles with only limited success and based many of his reforms on his experiences against the Poles?

Indeed the Polish army had many far-reaching influences on the development of Western armies, and was an important channel for the passing of Eastern military science to the West. The Polish army can claim to have introduced the uhlan lancer; and certainly had an influence on the hussar dress usually credited to Hungary. Through her close connections with the French court, Poland exerted other influences on the development of military uniform in the West, particularly on the long-cut jackets, grenadier caps, and dragoon uniforms of the 17th and 18th centuries. Wieslaw Majewski has even suggested that the modern divisional system had its origins in Poland via Luxemburg's teacher, the great Conde, a friend of Sobieski's wife Marie-Casimire.

Stefan Bathory, Prince of Transylvania and one of the most highly regarded of Polish kings (1576-86). He wears a bright scarlet fur-lined delta with decorative falling sleeves; under this, a tan and red patterned silk zupan with turnback cuffs of Eastern style; yellow ankle boots, and a black magierka Hungarian felt cap. Copy of a portrait by Marcin Kober, 1583. (Polish Army Museum - hereafter MWP)

Even ignoring its achievements, the Polish army of this period with its unique blend of East and West, its colour and unique character - is a fascinating subject within its own right.

I have chosen the period from 1569 (the Union of Lublin) to 1696 (death of Sobieski) simply because it covers the heyday of the Polish hussars. To go much earlier would involve treatment of fully armoured Western-style knights; while to continue after the Elector of Saxony, August 11, became King of Poland in 1697 would bring in the complication of the Saxon army.

This first title deals with the 'Polish Contingent' of the army, which includes the hussars, pancerni 'cossacks', and Hungarian-style infantry. The second title will discuss mainly the 'Foreign Contingent' of the army, Tartars and Ukrainian Cossacks, and other mercenaries in Polish service. This is not a straightforward division by nationality, since the 'Foreign Contingent' was for the greater part of the 17th century full of Poles, despite its name. There will be considerable overlap between the two books which are intended to be consulted together.

Much of the material presented here is previously unpublished even in Poland, and is based on research from primary sources, archives, and museums throughout Europe, and on the moun¬tains of Polish literature on the subject. Most valuable of all have been the works of Zygulski, Bocheński, Górski, Wimmer, Baranowski, Kotarski, Gembarzewski and Stefańska. It is im¬possible in a book of this size to quote all sources and discuss all arguments, and many statements are inevitably generalised. A short list of suggested reading will be given at the end of Part 2. In the meantime, interested readers would do well to read Volume 1 of Norman Davies' brilliant and entertaining history of Poland, God's Playground (London, 1981).

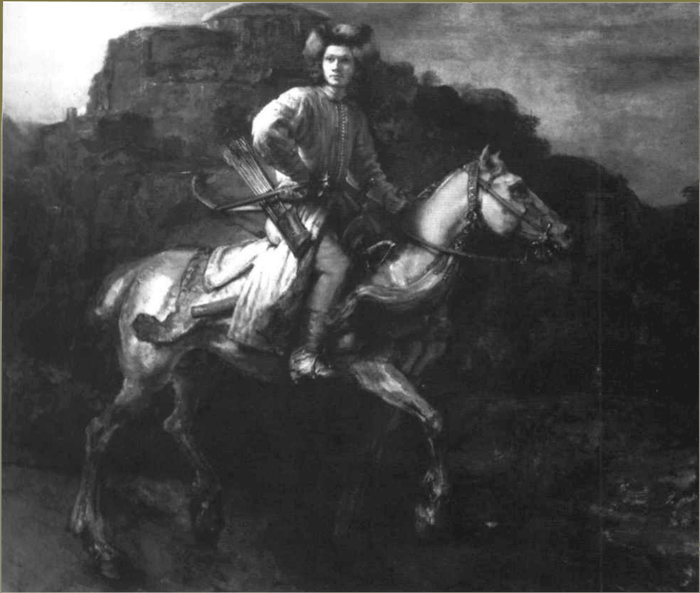

Rembrandt's famous 'Polish Rider': a source of much speculation, and often mis-labelled as an officer of the 'Lisowski' cossacks. Chrościcki (Ars Auro Prior, Warsaw 1981, p.441+) has finally identified it as a portrait of a Lithuanian nobleman, Martin Alexander Ogiński. From 1651 Ogiński was in military service. The portrait was painted in 1655 while Ogiński was studying in the Netherlands. The date of 1655 coincides with the devastating Swedish invasions, and suggests that Ogiński had the portrait painted on the eve of returning to his unit. He reached the rank of pulkownik in 1657, and later became Voivode of Troki, and Grand Marshal of Lithuania. His long coat is the zupan often worn beneath armour. When in the West, Poles usually adopted Western dress and hairstyles (as here) to avoid being laughed at for their unusual Eastern manners. (Frick Collection, New York)

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita)

Relations between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were brought closer by the accession of the Lithuanian Vladislav Jagiello (Jogaila) to the Polish throne in 1386. Lithuania had captured vast territories stretching deep into modern European Russia, but was increasingly finding that it could no longer cope with these on its own. The only place to which Lithuania could turn000

Hussar officer on a 'painted' horse. The dye is shown by the artist of the roll as bright red, although in practice the colour was probably a paler brick-red hue. From the 'Constantia' or 'Stockholm Roll' painted to commemorate the ceremonial entry of the Polish Queen Constantia of Austria into Cracow in 1605. (Royal Castle, Warsaw) for help was Poland. On the condition that the Ukraine was ceded 10 Poland, the two states were formally united in 1569 at Lublin in a union resembling that of England and Wales. In this way Poland took on the duty of protecting the Eastern expanses of Lithuania a task which was to have a significant effect in the orientation of Poland away from the West.

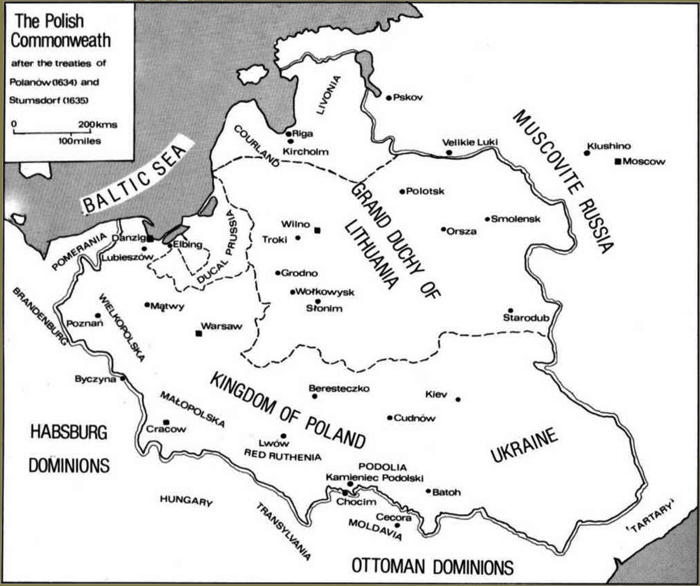

Together, the lands of Poland-Lithuania stretched from the Baltic almost to the Black Sea, and from the Holy Roman Empire to the gates of Moscow. In 1634 after the treaty of Polanów, when they were already past their greatest extent, they covered an area close to one million square kilometres the largest territory in Europe, slightly larger than European Muscovy and nearly double the size of France. With a total population of 11 million, Poland-Lithuania was Europe's third most populous state after Muscovy and France.

The territory of Poland-Lithuania was one vast plain: only in the south, along the Carpathian Mountains, was there an appreciable area of uplands. Canting across the plain were several major rivers, the most important being the Vistula, Neman, and Dnieper. These rivers and associated tributaries made transport very difficult, parti¬cularly along the line of marshes marking the Polish-Lithuanian border, which meant the two states were virtually cut off from each other in the summer. For this reason many campaigns into Muscovy did not get under way until winter, when the freezing of marshes and rivers made transport much easier.

The kingdom of Poland (usually referred to as the 'Crown') and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were governed by a single body, the Seym, to which both states sent representatives. Their territories were divided into województwa (palatinates), each gov¬erned by a wojewoda (voivode). Ziemie (lands), powiaty (districts), fortresses and towns were governed by a castellan or by a starosta (elder). Below these were a multitude of lesser titles: chamberlain, sword-bearer, cup-bearer, etc., many of them merely sinecures. Hereditary social ranks (such as duke, earl, etc.) were banned in Poland, so these titles took on a special meaning, and had the same status as Western hereditary titles without offending the egalitarian ideals of the Polish nobility. Only in Lithuania were some hereditary ranks retained as one of the conditions of the Union of Lublin. The famous Radziwill family, for instance, used the title ksiąze (duke) - though the award of the rank of 'prince' to a member of the family by the Austrian court led to screams of outrage when he attempted to use the title in Poland.

Poland had an unusually large nobility: ten per cent of the total compared with one to two per cent in the rest of Europe. The wealth of these noblemen varied hugely; but all, from the richest magnate to the poorest farmer, living in conditions as miserable as the peasantry, considered themselves equals. The Polish state was set up to serve the Polish nobleman: within it he had all the freedom he could wish for, so much so that visitors such as Sobieski's one-time English doctor Bernard Connor remarked: 'Had we in England but the third part of their Liberty, we could not live together without cutting one another's Throats'.

The nobleman's dress was worn virtually unaltered both at home and for war; and many of the fashionable items, such as swords and horse furniture, would be common to both. The adoption of foreign items of clothing during long campaigns abroad, often in conscious imitation of the enemy's dress, was the main influence on Polish fashion. A contemporary writer remarked, for example, on the rapid changes in dress throughout Poland in the space of only ten years, with Muscovite, Swedish and Turkish features each predominant in their turn after the return of armies from wars in these parts.

Noble dress was extremely expensive; and silks, satins, and velvets were not restricted to civilian use. For cavalry of the Polish model there was little in the way of centralised distribution of dress: men had to supply their own clothes, and they showed little restraint in displaying their wealth. The military theorist A. M. Fredro advised that lavish costume should not be brought into the camp. On his arrival in Poland King Bathory was shocked by the quantity of gold and silver being worn in the Polish army. Numerous laws were passed against sump¬tuous dress; but they failed to stamp out the love of splendour, and such items were widely worn on military service, particularly by the Levy of the Nobility.

Items of dress are often said to be of 'Turkish pattern' or 'Hungarian style'. These can sometimes be controversial, since it is difficult to determine the exact origin of any particular item: in Poland something might be called 'Turkish' while in Turkey it was known as 'Polish'. To complicate the problem even further, a term used for a particular item in one country often indicated an entirely different thing in another.

For a large part of our period, Hungarian dress was dominant; indeed, it is often difficult to distinguish between Hungarian and Polish styles. Some historians have suggested that King Bathory introduced Eastern and, particularly, Hungarian dress into Poland after his election in 1576; however, by the end of the Jagiellonian dynasty in 1572 most of the army and the nobility were already dressed in Hungarian style. Indeed, it seems more likely that the proliferation of Hungarian dress and custom had an influence on Bathory being elected in the first place.

Hungarian dress in turn owed a great deal to Turkish and Persian influences, and these also fascinated the fashion-conscious in Poland through¬out the period. Numerous contracts were carried out in Istanbul for Polish patrons, but these alone could not satisfy the huge demand. Many workshops opened up in Poland, staffed largely by Armenian craftsmen making weapons and other items in Turkish style.

The appearance of Poles abroad, especially on missions to the West, caused reactions varying from ridicule to sensation: Cossack and Tartar hairstyles that would put many a modern 'punk' to shame, eagle- and ostrich-feather 'wings', cloth-of-gold, precious silks even solid gold and silver horse¬shoes, fastened loosely to ensure that they would fall off conspicuously during ceremonial entries! City populations turned out en masse to witness these splendid processions; and even the ever-fashionable

Hussar armour, c. 1540-70. Note that the mail is of a type known an bajdana, made of especially large rings. The pointed Eastern-style szyszak helmet has yet to evolve into a typically Polish style. Circular metal shields, some with fringed edges, were used as well as wing-shaped shields. (MWP) ladies of Paris designed themselves new costumes in the fear that they would be outshone by the splendid dress of the Polish delegations.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com