ANTONY PRESTON, JOHN BATCHELOR

THE SUBMARINE SINCE 1919

In both the First and Second World Ways, the submarine came close to winning a decisive victory. Twice, it almost succeeded in cutting off Britain's supply routes and completely crippling the Allied war effort in Europe. Today, however, those achievements pale in comparison with the almost limitless power of the ICBM-armed nuclear submarine.

In this book we take up the story of the submarine at the end of the First World War, when it had uncontestably claimed a major place in the arsenal of any military-minded nation. We trace its development in the inter-war period, its vital role in all the major theatres of the Second World War. And, through Antony Preston's readable and authoritative text, and John Batchelor's magnificent illustrations, we follow the story up to the present day.

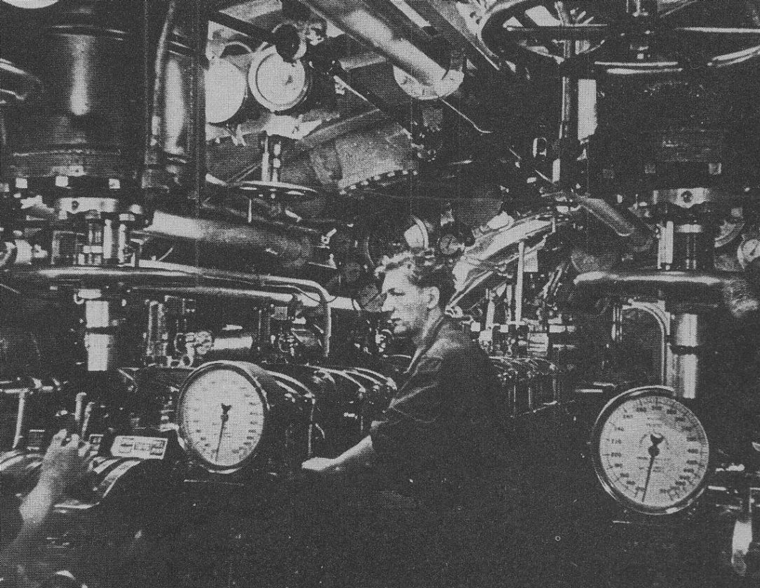

The engine room of a British submarine with the engines cut and the crew at action stations waiting for the signal to dive

Antony Preston was born in 1938 and educated in South Africa. He worked for some time as a research assistant in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. He has written numerous reviews and articles on warship design and aspects of 19th and 20th century naval history for various journals, and periodicals. Among his books are Send a Gunboat (with John Major), V & W Destroyers, and Battleships of World War 1.

John Batchelor, after serving in the RAF, worked for three British aircraft firms in their technical publications departments. He then contributed on a freelance basis to many technical magazines, as well as the boys' magazine Eagle, before starting what was to be a marathon task of over 1,000 illustrations for Purnell's Histories of the Second World War and First World War. He takes every opportunity to fly or sail in, shoot with, or climb over and photograph any piece of military equipment he can find.

BETWEEN THE WARS. A WHOLESOME RESPECT

The experience of the First World War had left no doubt of the military value of the submarine. As victors and vanquished alike gradually began the inevitable re-armament, they could not afford to ignore the new weapon - and, for the Allies at least, the surrendered German U-Boats provided a good starting-point

When the exhausted world powers turned to negotiation in 1918, as an alternative to the four years of destruction which had been endured, it was with a wholesome respect for the submarine. Whether the war would have ended sooner without the submarine is arguable, but there can be no doubt that it would not have been so ruinously expensive. The British Empire, having started the war as the world's largest ship-owner and operator, lost over 9 million tons, as against 4 million tons lost by all other countries put together. This represented about 90 per cent of the steamships under British registration in 1914, and the loss of national wealth went far beyond the actual cost of the cargoes.

The submarine had proven its worth as a fighting weapon during the First World War, as the fearful slaughter of ships showed only too well. When the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918 between Germany and the Allies, one of the key clauses stipulated that the U-Boats must be surrendered at a designated port. All boats fit for sea had to retain their armament, but those unfit for sea were to be disarmed and immobilised.

On the morning of 20 November a melancholy profession began, with batches of U-Boats going to the British east coast port of Harwich until the early months of 1919; others surrendered at Sevastopol or in neutral ports, and even more were put out of action in German ports. A total of 176 boats were surrendered, and immediately the victors seized the chance to study the sinister weapon which had cost them so much in blood and treasure. The U-Boats were parcelled out as follows:

Great Britain

105 boats, of which at least U126, U161 and one of the UC90 class wore the White Ensign for a time

France

46 boats of which 10 were incorporated into the French Navy and renamed: U79/Victor Reveille; U162/Pierre Marrast; U105/Jean Autrice; U166/Jean Roulier; U108/Léon Mignot; UB98/Trinité Schillemans; U119/Réné Audry; UB99/Carissan; U139/Halbronn; UB155/Jean Corré

Japan

7 boats renamed UC90-O3; U125-O1; UC99-O5; U46-O2; UB125-O6; U55-O3; UB143-O7

Italy: 10

USA: 6

Belgium: 2 originally allocated to Great Britain

With the exception of the ten French boats listed, all these submarines were scrapped and disposed of by 1922/23 by agreement between the nations concerned (the French arrangement having been a special case) to compensate for wartime losses. But the lessons had been learned and would be incorporated in future construction.

Despite the fact that wartime experience had not justified the "U-cruiser" type, with its large, clumsy hull and superfluous heavy guns, every navy plumped for cruiser-submarines. The two nations whose navies were expanding rapidly were Japan and the United States, and both took possession of the larger types of U-Boat as their share of surrendered tonnage. The United States took over U140, a 311-ft vessel armed with two 5·9-in guns, and incorporated many of her features into the so-called V-series, the Barracuda Class, and the Narwhal Class, both with high endurance and heavy torpedo-armament, and in the case of the two Narwhals, having two 6-in guns. The sixth in the V-series was the giant Argonaut which was also based on U140, but incorporated the minelaying system of the UEII type U117, which was also among the US Navy's booty.

The first Japanese cruiser-submarine was the I52 laid down in 1922, and she was modelled on the O1 (ex-U125), another UEII type. A year later an even larger type, the "Junsen Type 1" or Cruiser Submarine Type 1 was begun; the four vessels I1-4 displaced 2,135 tons on the surface and 2,791 tons submerged, had an armament of two 5·5-in guns and carried 20 torpedoes. In 1926 I1 showed her capabilities by cruising for 25,000 miles and diving to 260 ft, the deepest dive recorded by a Japanese submarine up to that date. No mines were carried, as the minelaying features of the UEII type were incorporated in a further class, the 121-24, which approximated more closely to the original design in size.

American Nautilus. The USS Nautilus and her sister Narwhal were armed with 6-in guns, and copied many features of the German U117 type of the First World War. They came into service in 1930/31 and served in the Pacific throughout the Second World War. Four additional external torpedo-tubes were added during the war

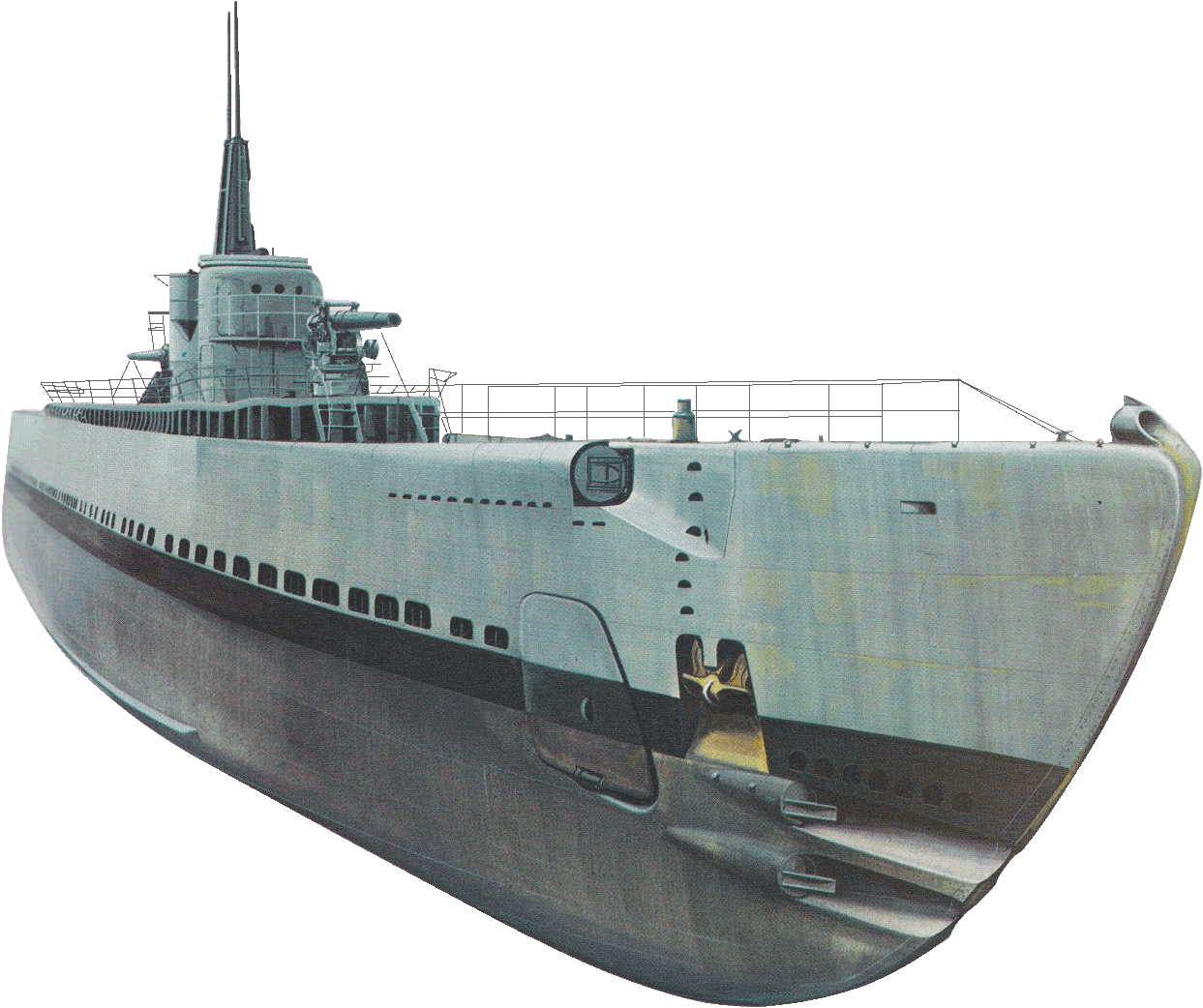

The British also rushed headlong into experiments with cruiser-submarines, and in 1923 they launched the giant X1 under conditions of exaggerated secrecy. She was based on the uncompleted U173 class of giant U-cruisers, and even used similar M.A.N, twin diesels for surface running. German diesel engines had enjoyed a high reputation for reliability, but in this case they proved to be the reason for many of X1's problems; although extremely safe and capable of diving very deep, with a radius of 12,400 miles on the surface, she was plagued by mechanical troubles and was finally scrapped after only five years' active service. Thereafter British interest in giant submarines lapsed, and only the French stayed in the game, with their Surcouf.

Nothing if not logical, the French took the terms of the Washington Treaty at face value, and as the Treaty stated that submarines might carry guns no bigger than 8 in, that was the calibre chosen. This unique submarine carried not only a seaplane but a twin 8-in turret and twelve torpedo tubes, with ten reloads. An interesting innovation was the provision of a quadruple mounting for firing small (15·7-in) torpedoes against merchant ships; although fast, these torpedoes had a range of only 1,500 yards.

Although the Italian Navy developed large submarines from their UEII type, U120, they avoided the extreme examples produced elsewhere. While the number of torpedo-tubes was increased, the gun-calibre was kept down to 3·9 in or 4·7 in, thus avoiding the chief pitfall of the big submarine.

British experience in the recent conflict had taught them one thing, the need for a heavy bow salvo of torpedoes to give greater accuracy at long ranges. This arose because, unlike U-Boats, British submarines had normally attacked well-defended warships. The knowledge that anti-submarine tactics had improved beyond all measure, and would continue to do so, led British submariners to accept the need to fire from a greater distance, and so from the L52 class of 1917, British submarines had a standard armament of six 21-in bow torpedo tubes. By comparison, Japanese and American submarines still had only four bow tubes at the expense of two stern tubes, and German U-Boats had largely been armed with two bow and two stern tubes, although in the later boats an extra pair was fitted.

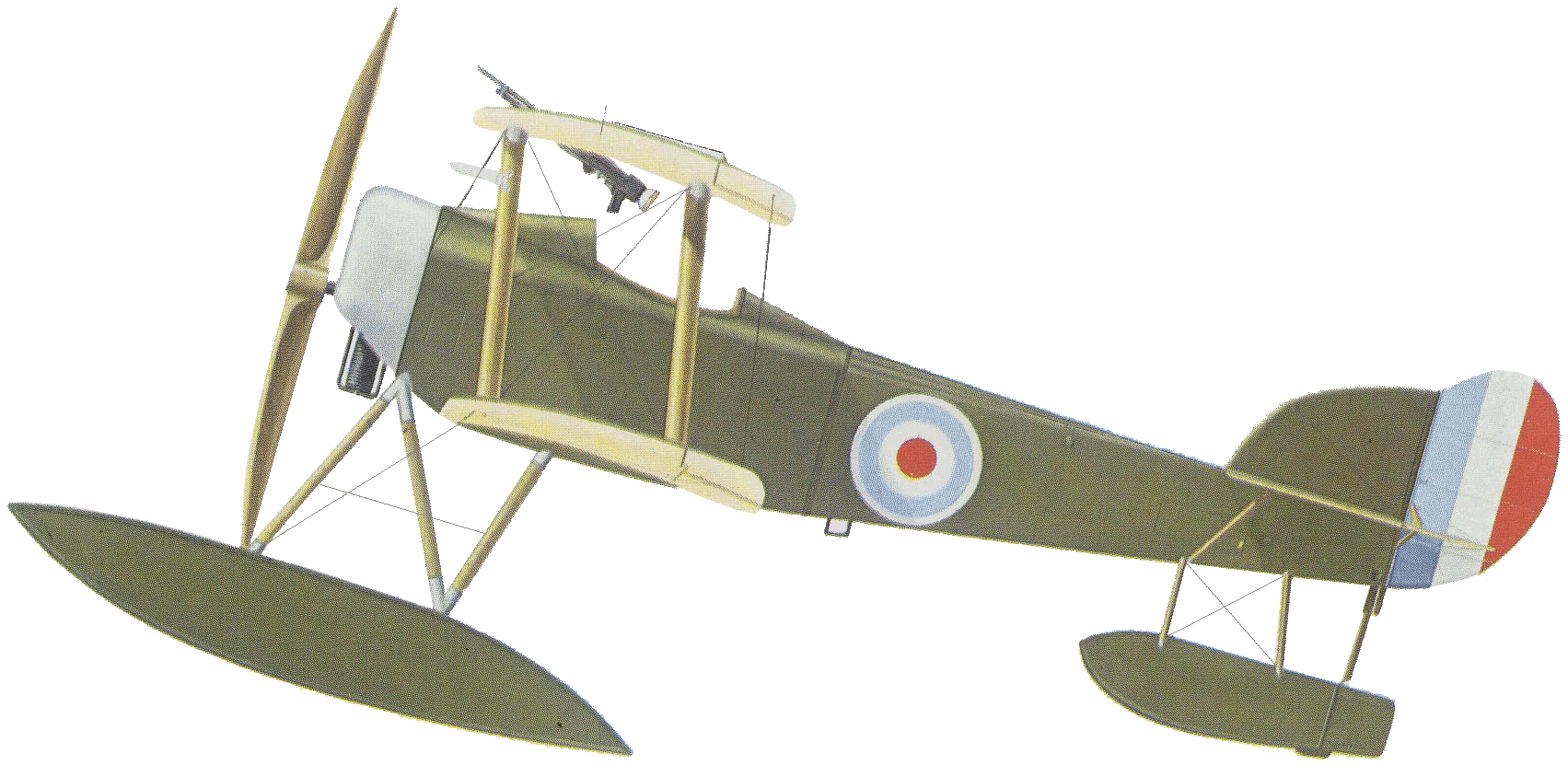

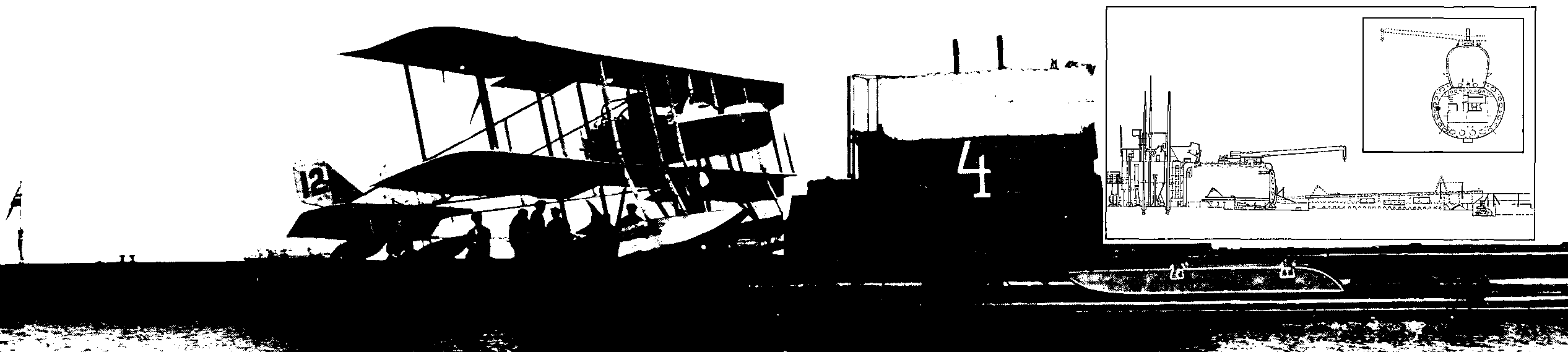

The other important development in the years after the Armistice was the operation of aircraft from submarines. War experience had shown the importance of reconnaissance to the submarine, especially for locating targets when operating in distant waters. In January 1915 U12 had operated a Friedrichshafen FF-29 off her foredeck, and in April 1916 the British E22 flew off two Sopwith Baby seaplanes from a stern ramp. This latter experiment was an attempt to extend the range of seaplanes to shoot down Zeppelins rather than to extend the submarine's capability, but it did prove the feasibility of the idea. As early as October 1915 the Admiralty had considered the need for a watertight hangar, but this idea had to wait until after the war. The Germans built three small Hansa-Brandenburg W-20s in 1917, and the V-19 Putbus for operation from U-Boats, but these were never used at sea.

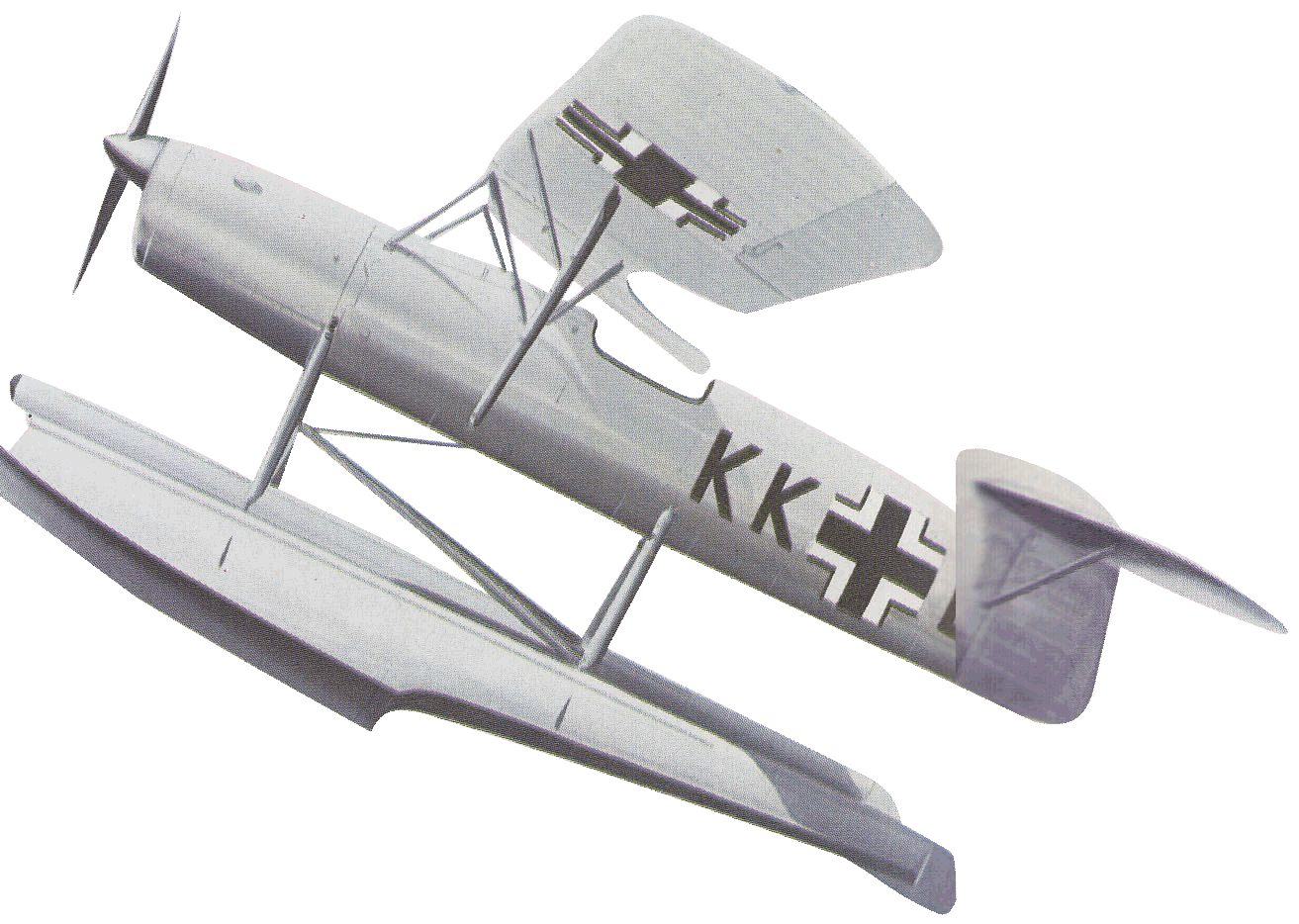

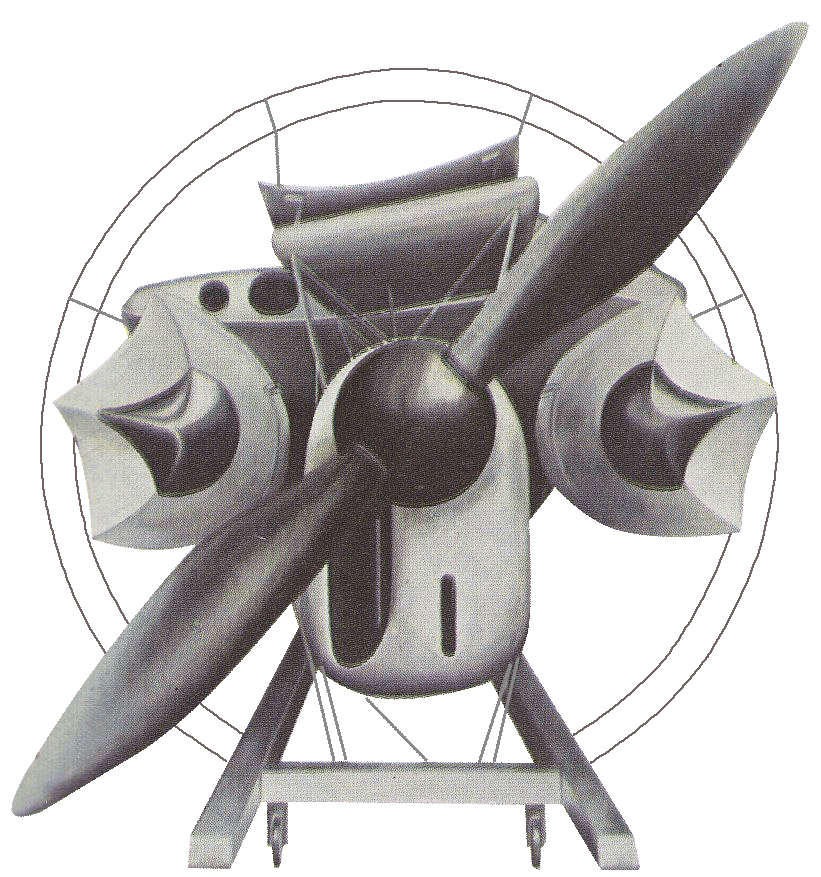

German Arado 231 Seaplane. The single-seater Arado 231 was intended to be launched from U-Boats, although no U-Boat seems to have been designed to meet this requirement. Naturally the design was restricted by limitations on size, and the aircraft could only fly 310 miles at a maximum speed of 106 mph. The wing span of 33 ft 4.5 in could be reduced to 6 ft 6.5 in when folded (above), and the length was 25 ft in

By 1919 the aircraft themselves had developed, and it was not long before experiments were put in hand. In 1923 the United States Navy submarine S1 appeared with a tubular hangar abaft her conning tower. This housed a folding seaplane, which could be run out to the stern after assembly, but as no catapult was provided the seaplane had to taxi before takeoff. The experiment proved quite satisfactory, and a specially designed aircraft was built, the Martin Kitten, but the idea was killed off by lack of funds.

In 1925 the British decided to remove the 12-in guns from their two surviving "M" Class submarines, and M2 was converted to carry a seaplane. A large hangar was built forward of the conning tower, with a large crane on its roof; a light inclined catapult was built on the forward casing, and a specially designed Parnall Peto seaplane was carried. The biggest problem of handling an aircraft on board a submarine was the lack of space, and this dictated very small machines, which in turn lacked the capacity for fuel which would have made them more useful.

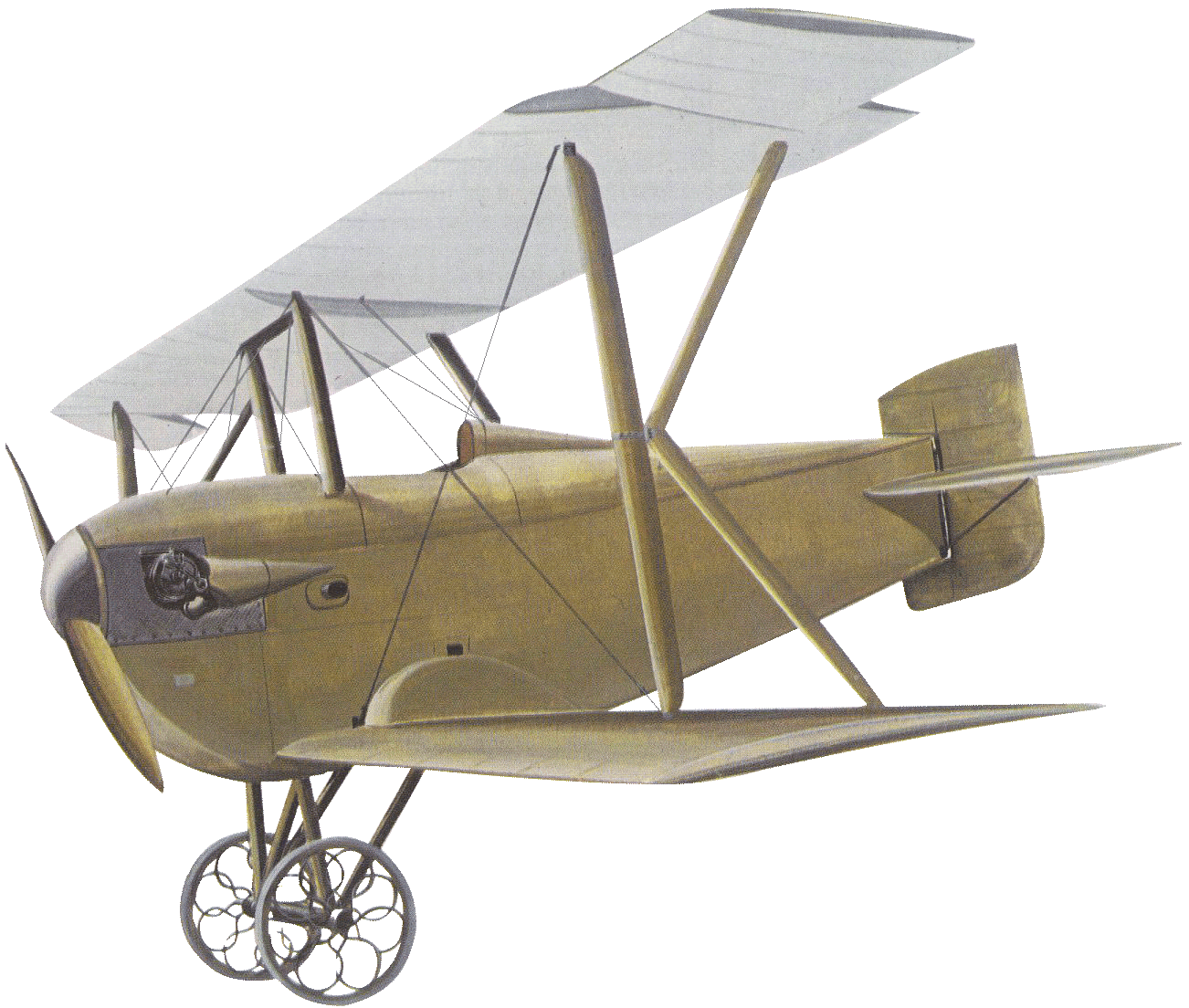

Sopwith Baby. With its 25 ft 8 in wingspan and maximum speed of 100 mph, the Sopwith Baby was successfully flown off a British submarine in 1916. Performance and range were too limited to produce any positive results, however, as was the case with similar experiments with German U-Boats

Then, in 1932, the Japanese launched their prototype 15. They stowed the fuselage and floats in one hangar and the wings in another, sited to port and starboard under the conning tower. The time taken to assemble the seaplane was so long that the submarine would almost certainly have been sunk in the middle of the operation. The 16 had the same problem, but she did at least have a catapult like the M2. Thereafter a seaplane and catapult became a feature of the larger types of Japanese submarines, and special tactics were devised to exploit the combination.

In 1916 the Norwegian Navy bought Farman floatplanes for trials, and when they broke down or ran out of fuel submarines were able to recover them by surfacing gently underneath. In this photograph a recovered seaplane is being lifted off the casing of submarine A4. Note the spare float lashed to the submarine's casing

British M2 Hangar. In 1925 the two surviving 12-in gunned submarines M2 and M3 had their guns removed. To test the concept of using aircraft to seek targets for submarines, M2 was equipped with a hangar forward of the conning tower, and a catapult. She could operate a single Parnall Peto

The sister of M2 was converted to a minelayer at the same time, as a development of the U71 type. M3 had a free-flooding casing (i.e. outside the pressure hull) containing twin mine-tracks, which ran from well forward past the conning tower. She was a great success, although ungainly in appearance, and she was followed by a class of six more. The main innovation in the M3 was the provision of powered chain conveyor gear, which allowed the use of a normal mine and sinker, rather than the special type of mine which had to be used in all First World War minelayers.

The Washington Disarmament Conference of 1921/22 and the Treaty which resulted were the outcome of the rivalry which had grown up between the United States and Japan during the First World War. Although the Treaty is best known for its limitations on large surface warships, it also dealt with submarines. The British delegation was not unnaturally content to see the submarine banned, but this was a futile quest so soon after the great submarine campaign of 1915-18. The Italians and French were particularly anxious to retain a large fleet of submarines as a cheap alternative to new battleships and aircraft carriers, and the Japanese made little secret of their intentions to build up a big fleet to threaten American superiority in the Pacific. Lord St Vincent's words of 1801 had come true, and neither of the two largest navies really wanted to see any progress made with the weapon most likely to destroy their own superiority.

Stored German Arado 231

The best that could be done was to limit the gun-calibre to 8 in, as in heavy cruisers, but the French were particularly obdurate in rejecting limitations on numbers of submarines and in blocking attempts to outlaw unrestricted warfare. The world's major navies, denied the opportunity of building unlimited numbers of surface warships as much by economics as by international agreement, plunged into an orgy of submarine building.

The smaller navies were also conscious of the value of submarines, and the Nether-lands and the Scandinavian countries had developed their own designs with some success. The Royal Swedish Navy had been building submarines since 1908, but the first fully indigenous design, the Sjölejonet Class, was not ordered until 1934. They displaced 580 tons on the surface, were 210 ft in length, and had a submerged speed of 9 knots. The disposition of torpedo tubes was unusual - three 53-cm (21-in) bow tubes, two rotating deck tubes similar to those on French boats, and a single stern tube; two single 40-mm deck guns were carried in retractable mountings, an idea derived from Dutch submarines. Three were completed in 1938/9, and a further six were ordered when the international situation worsened.

Martin Kitten. The Martin Kitten was the first aircraft specially designed for operating from submarines. 4 were ordered in 1922 but only one prototype survives. It is unusual in having wingtip ailerons and also in having wheels instead of floats. This meant that the aircraft had to do a crash-landing after completing its mission, but the cockpit is so cramped that the pilot would have extreme difficulty in baling out. In fact, pilots would probably have been chosen for their lack of stature and expendability if it had gone into service

Denmark lacked the resources of Sweden, but she too produced original designs like the "H" Class, whereas Norway was more content to rely on foreign designs. The "B" Class were completed in the early 1920s to an American Electric Boat Company design of 1914 vintage, but B1 nevertheless served in the Second World War. Poland had a small force of five boats, comprising the Dutch-built Sep and Orzel and a trio of French-built 980-tonners, the Rys, Wilk and Zbik, of which the Orzel and Wilk managed to escape to Britain in September 1939 in a desperate dash for freedom.

Cruiser-submarine comparative specifications

| Cruiser-submarine comparative specifications | |||||

| Type | Tonnage (surf/sub) | Length/Beam (ft) | Speed (kts) (surf/sub) | Guns | Torpedoes |

| U117 (Germ.) | 1164/1512 | 276·5/24·5 | 14·7/7 | 1x5·9 in | 4x20 in (20 reloads) |

| U139 (Germ.) | 1930/2483 | 311/29·75 | 15·8/7·6 | 2x5·9 in | 6x20 in |

| U151 (Germ.) | 1512/1875 | 213·25/29·25 | 12·4/5·2 | 2x5·9 in; 2x3·4 in | 2x20 in |

| U173 (Germ.) | 2115/2790 | 320/29·75 | 17·5/8·5 | 2x5·9 in; 2x3·4 in | 6x20 in |

| Barracuda (US) | 2000/2620 | 341/27·25 | 18/11 | 1x5 in | 6x21 in |

| Argonaut (US) | 2710/4080 | 381/34 | 15/8 | 2x6 in | 4x21 in |

| Narwhal (US) | 2730/4050 | 371/33·25 | 17/8 | 2x6 in | 6x21 in |

| X1 (UK) | 2425/3585 | 363·5/29·75 | 19·5/9 | 4x5·2 in | 6x21 in (6 reloads) |

| Surcouf (Fr.) | 2880/4304 | 361/29·5 | 18·5/10 | 2x8 in | 8x21·7 in (10 reloads) 4x15·7 in |

| I52 (Jap.) | 1500/2500 | 330·75/25 | 22/10 | 1x4·7 in; 1x3 in | 8x21 in (9 reloads) |

| I1 (Jap.) | 2135/2791 | 320/30·25 | 18/8 | 2x5·5 in | 6x21 in (14 reloads) |

| Ettore Fieramosca (Ital.) | 1556/2128 | 275·6/27·25 | 19/14 | 1x4·7 in | 8x21 in (6 reloads) |

The Dutch had originally built two types of submarine, those with "K" numbers for the East Indies, and those with "O" numbers for home waters, but in 1937 the two series were combined under "O" for "Onterzeeboot". The O21 class of five boats were laid down in 1937/38 for general service at home and in the Far East. They were conventional in all ways but one: they were the first to incorporate an "air mast" for charging batteries while running at periscope depth, a vital step in extending the submerged endurance of submarines.

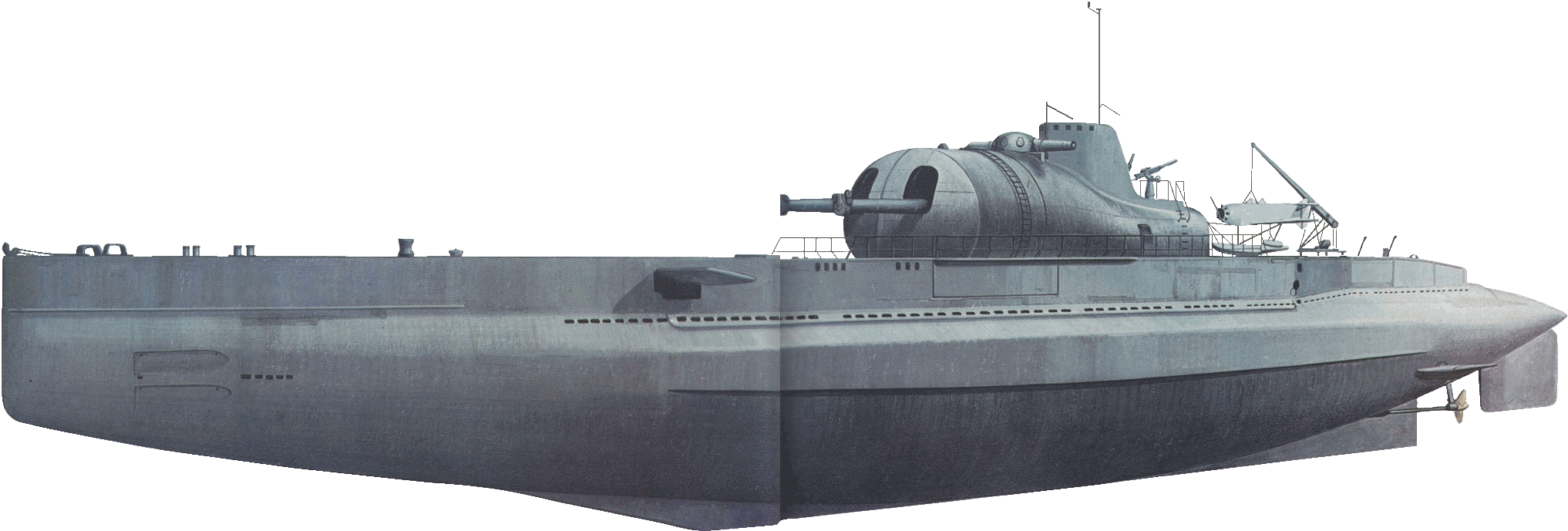

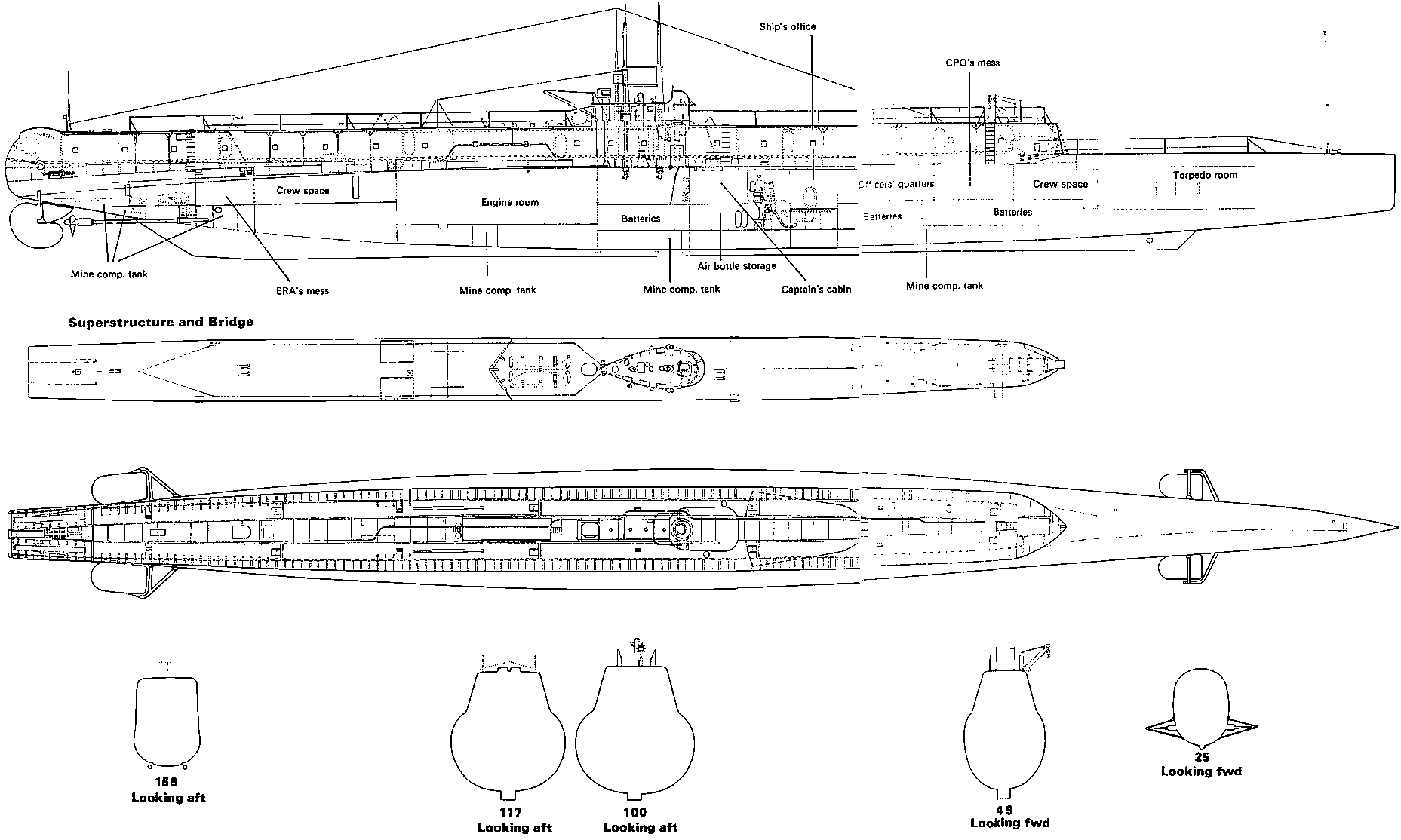

British X1. X1 was the largest British submarine ever built until the advent of nuclear propulsion, and was in many ways superior to other cruiser-submarines. Her radius of action was 12,400 miles on the surface, and she could remain submerged for over two days, thanks to her large battery capacity. In addition, her two twin gun-mountings were carried high above the waterline to free them from spray interference, but despite all these advantages her unreliable machinery prevented her from being a success

Alas, like other prophets the Dutch were without honour in their own country, and with their Allies for that matter; when O21-24 arrived in England in May 1940 the first thing the Royal Navy did was remove the air masts, and only in 1943 did the Germans realise the worth of the gadget they had found in a Dutch shipyard. Looking around in desperation for an antidote to the danger of recharging batteries on the surface at night, when aircraft and escorts were using radar, they re-examined the air mast and perfected it as the "schnorchel".

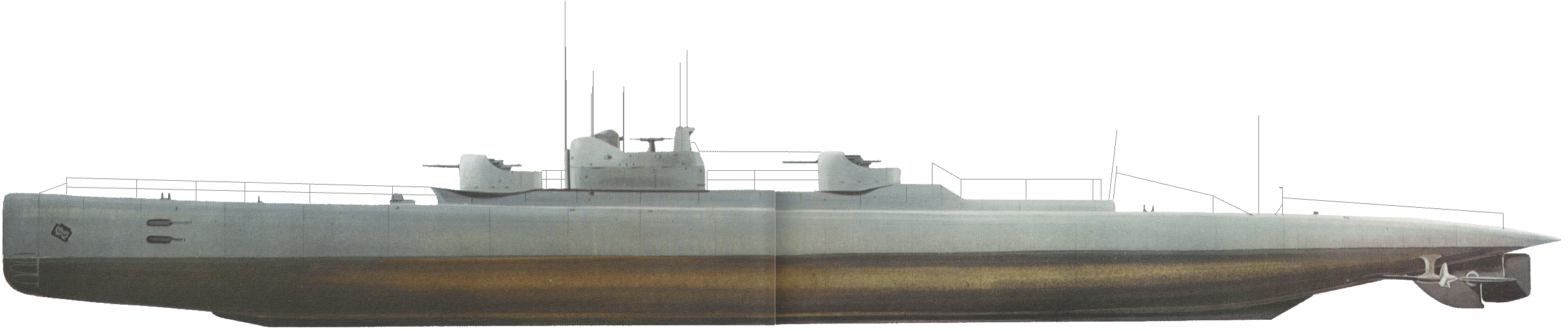

French Surcouf. Not only the largest submarine in the world, the Surcouf was also the only one to have the maximum calibre of guns allowed under the Washington Disarmament Treaty. Her 8-in guns were carried in a twin power-operated turret, and could each fire three 260-lb shells per minute to a range of 30,000 yards. In addition, she carried a seaplane in a cylindrical hangar abaft the conning tower. She operated under the Free French flag in the Second World War, but was accidentally rammed by an American freighter in 1942

After their spectacular experiment with the Surcouf the French Navy reverted to more conventional submarines. In March 1920 the Chairman of the Naval Estimates Committee in Parliament had suggested quite seriously that a fleet of 250 to 300 submarines would answer all needs hitherto met by cruisers and battleships. Fortunately this extreme argument was met by a reasoned rebuttal, for it was clear to naval officers that, despite its potency, the submarine had only recently suffered a catastrophic defeat. Furthermore it was correctly argued that on a ton-for-ton basis the complexity of a submarine made it just as expensive as a surface ship to build and maintain, and also reduced its effective life. Although submarines were to be built in large numbers, they were nonetheless part of a balanced fleet. Two types were built after 1922, 1st Class boats of some 1,000 tons, and 2nd Class boats of 600 tons, the larger being intended for overseas patrol duties and the smaller ones for defensive patrol duties in home waters.

British M3. Submarines were forbidden to have guns larger than 8 in by the terms of the Washington Disarmament Treaty, so the "M" Class were disarmed and converted. M2 was converted to enable her to launch a Parnall Peto seaplane, while M3 became a minelayer. By stowing her mines inside a large free-flooding casing outside the main hull, she was able to use normal mines, which were laid over her stern by means of a chain-conveyor gear. She paved the way for the highly successful Porpoise Class, and was scrapped in 1932

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com