J. ARNOLD, S. SINTON, illustrated by DARKO PAVLOVIC

US COMMANDERS OF WORLD WAR II. NAVY AND USMC

Born in 1889 in Indianapolis, Indiana, Norman Scott received his commission from the US Naval Academy in 1911. He was the executive officer aboard a destroyer when it was sunk by a German submarine in December 1917. During this incident, he exhibited stellar conduct. During the interwar years, Scott served as naval aide to President Woodrow Wilson, held various staff and line assignments, including a three-year stint as instructor at Annapolis, was a student at the Naval War College, and command of the heavy cruiser Pensacola. When the United States entered World War Two, Scott was serving on the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations. According to Admiral Spruance, Scott "made things so miserable for everyone around him in Washington that he finally got what he wanted - sea duty."

Admiral Norman Scott was the first flag officer to fight a surface engagement in the Pacific with a carefully prepared battle plan. The resultant October 11-12, 1942 Battle of Cape Esperance made Scott a national hero. (US Naval Historical Center)

Rear Admiral Scott commanded a light cruiser division during the August 9, 1942 Battle of Savo Island. His forces did not engage during this terrible American defeat. He commanded a three-ship cruiser division assigned to defend the carrier Wasp during the August 24 Battle of the Eastern Solomons. An aggressive leader, his great opportunity came at the October 11-12, 1942 Battle of Cape Esperance. He had orders to protect a convoy sailing to Guadalcanal by offensive action. His orders required him to search for and destroy enemy ships and landing craft. Scott had studied previous night actions against the Japanese. He worked out a careful battle plan and trained his units intensively for three weeks to execute the plan. He conditioned his crews for night action by keeping them at their stations from sunset to dawn. Scott was also the first surface task force commander in the Pacific to enter battle with a carefully prepared battle plan. He instructed his ships to proceed in column, with destroyers in the van and rear. Destroyers were to illuminate with searchlights, fire torpedoes at large ships, and use their guns against smaller targets. Cruisers were to engage with gunfire without waiting for orders.

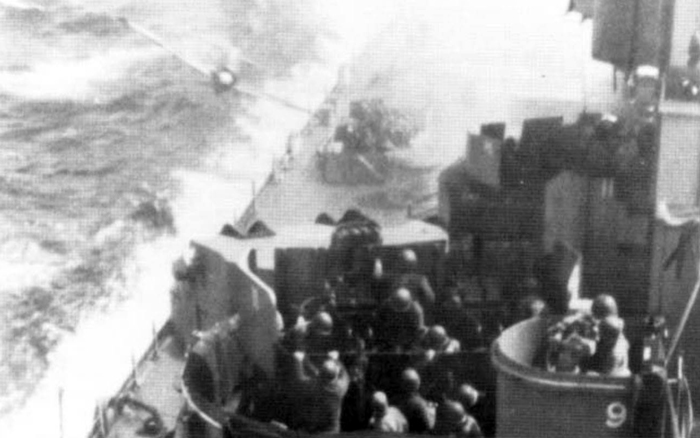

Superceded by Admiral Daniel Callaghan, who was a personal friend of President Roosevelt, Scott was relegated to a subordinate role on the night of November 13, 1942. He died in the opening moments of the battle, while aboard the antiaircraft light cruiser Atlanta. The Atlanta, shown here, later sank. (US Naval Historical Center)

Neither Scott nor his contemporaries understood how best to utilize the American radar advantage during a night action against the Japanese. (US Naval Historical Center)

The Battle of Cape Esperance proved to be a complicated, confused Fight. Scott had to order a countermarch shortly before the engagement began and this placed his ships in an awkward tactical situation. Moreover, at a crucial time, he mistakenly ordered a ceasefire because he thought that his ships were shooting at one another. Nonetheless, during the battle, his cruiser and destroyer task force managed inadvertently to "cross the T" of the Japanese cruiser force. The subsequent qualified success at the Battle of Cape Esperance marked the first time that the Japanese suffered a defeat in a night battle involving evenly matched surface forces. Over-optimistic reports of Japanese losses elevated Scott to hero status. In reality, the battle helped American morale but failed to prevent the Japanese from reinforcing Guadalcanal. Moreover, Scott had employed faulty tactics that succeeded more from luck than design. However, he fought the battle bravely and never allowed it to degenerate into a wild ship-to-ship mêlée.

In November, a desk officer whose commission antedated Scott's by a few days, Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan, superceded Scott. Under Callaghan, Scott flew his flag aboard the anti-aircraft cruiser Atlanta. On November 12, 1942 Admiral Turner learned that a heavy Japanese force was steaming toward Guadalcanal. The only forces available to check them were Callaghan's two heavy and three light cruisers along with eight destroyers. Turner ordered Callaghan to stop the Japanese Navy at all costs. A month earlier, Admiral Nimitz had predicted that Guadalcanal could be defended only "at great expense to us." His words were prescient. On the night of November 13, 1942 (Callaghan emulated Scott's long, single column formation. The result was an exceptionally confused night action in which the American vessels plunged into the middle of a Japanese formation that included two battleships. At the very close range of 1,600 yards, the battle began. Japanese searchlights illuminated the Atlanta's bridge. Shells rained down on the Atlanta, killing Scott and all but one of his staff. Later, Callaghan also died. Scott received a posthumous Congressional Medal of Honor for his conduct. Vandegrift eulogized the two admirals and their crews for "their magnificent courage against seemingly hopeless odds."

Scott is best remembered for his leadership at the Battle of Cape Esperance. In the words of Samuel Eliot Morison, the foremost American naval historian of the war, he fought the battle "with a cool, determined courage."

Born in Natlee, Kentucky in 1888, Willis Lee graduated from Annapolis in 1908 and received his commission two years later. Lee's first duty after graduation was aboard a battleship. He remained a "battleship sailor" for the rest of his life. In 1914, he participated in the Vera Cruz expedition and served aboard destroyers in the Atlantic during World War One. Lee was an expert rifleman. While on the US team at the 1920 Olympics, he won five gold medals. Lee graduated from the Naval War College in 1929. During the interwar years, he held a variety of commands, including more destroyer service and command of a light cruiser. In July 1938, Lee became operations officer to the Commander Cruisers, Battle Force. Thereafter, he served this force as chief of staff to the Commander Cruisers. Holding the rank of captain, in June 1939 Lee became assistant director of fleet training. In January 1941, he was elevated to head of the fleet training division. In this capacity, he was responsible for training the large influx of sailor recruits who were to man the navy's newly constructed ships. Promoted to rear admiral, in February 1942 Lee became chief of staff to the Commander-in-Chief United States Fleet, Admiral King. After six months' service, he received the command he most coveted, commander of Battleship Division Six, Battleships, Pacific Fleet. For the remainder of his active service, Lee commanded battleships, rising to the rank of vice admiral in command of Battleship Squadron 2.

Unlike most senior officers, Lee studied modern technology and understood radar. He "knew more about radar than the radar operators." He put this knowledge to good use and played an important role in defeating the final Japanese effort to capture Guadalcanal. Lee was especially motivated to perform well during this operation because the Marine General Vandegrift, who had led the invasion of Guadalcanal, was a longtime friend. American carriers had recently suffered so severely that Admiral Halsey decided to block the Japanese using his new, fast battleships. Accordingly, Lee took Task Force 64, his first independent flag command, composed of four destroyers and the battleships Washington and South Dakota, to intercept a Japanese force. The enemy force, which included a battleship, was intent on bombarding Guadalcanal.

During the ensuing Naval Battle of Guadalcanal on the night of November 14-15, 1942, Lee lost three of his destroyers and scores of men during the initial exchange. A power failure aboard the South Dakota caused that ship to become a helpless target of the Japanese heavy ships. Only Lee's flagship, the Washington, was undamaged. Through it all, Lee remained imperturbable. Near midnight, the Washington's radar locked onto a Japanese battleship and mortally wounded it with a withering barrage; nine 16-inch shells and 45-inch shells hit in less than seven minutes. The burning battleship retreated, accompanied by the rest of the Japanese fleet. Lee took the Washington on a solo nighttime search for enemy transports. Failing to find any, he gave up the search at dawn only to confront torpedoes launched from two enemy destroyers. The Washington managed to dodge the torpedoes. The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, a series of actions that included Lee's fight with his beloved battleships, was hugely significant. In the words of naval historian, Samuel Eliot Morison, the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal "was decisive, not only in the struggle for that island, but in the Pacific War at large." It marked a definitive American shift from the defensive to the offensive and a corresponding Japanese loss of offensive initiative.

Known for having "one of the best brains in the Navy, Willis "Ching" Lee displayed the capacity for quick decisionmaking on the night of November 14-15. During the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, a ferocious night surface action, Lee kept his head and displayed calm reasoning. In the words of naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison, "An able and original scientist as well as flag officer, [Lee] appreciated the value of radar, used it to keep himself informed of enemy movements and tactics, and made quick, accurate analyses from the information on the screens." (US Naval Historical Center)

At the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Rear Admiral Willis Lee's flagship was the new battleship Washington. This battle was one of three battleship-to-battleship actions of World War Two. The others were the Battle of Calabria, June 27, 1940 and the Battle of Surigao Strait, October 25, 1944. In addition, the Prince of Wales fired at the Bismark during the latter's last fight. (US Naval Historical Center)

After the Solomons campaign, Lee's ships supported the series of amphibious assaults that catapulted US forces through the Central Pacific. Lee received promotion to vice admiral in March 1944. During the Marianas campaign in June 1944, Lee's battleships had a chance to engage the Japanese in a night action. However, his big ships had spent all of their time recently supporting the carriers, and this duty exclusively involved anti-aircraft defense. They had not practiced surface engagements of any sort, let alone a night action. As one of Spruance's officers noted, "He'd had a lot of experience in night attacks and most of it had." Consequently, with Spruance's concurrence, Lee declined to seize the chance. Late in the war, Lee received the assignment of developing tactics to combat the Japanese kamikaze attacks. He died from a heart attack aboard a launch taking him to his flagship in August 1945.

Admiral Halsey presents the Navy Cross to Willis Lee for his leadership at the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. (National Archives)

Known to his friends as "Ching" Lee, Willis Lee was the most notable American battleship admiral of World War Two.

Charles Lockwood was born in 1890 in Midland, Virginia. Raised in Missouri, he received a commission from the US Naval Academy in 1912.

At the age of 24, in 1914 he commanded a submarine, and by 1917 commanded a submarine division. After a brief stint aboard a surface ship, he returned to submarines and commanded the ex-German submarine, UC-97, from March until August 1919. During the interwar years, Lockwood held both surface and submarine commands, including duty on the Yangtze Patrol off China, served as a member of the US Naval Mission to Brazil, and taught at Annapolis. In the fall of 1937, he served in the office of the Chief of Naval Operations and then became chief of staff to Commander Submarine Force. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor found Lockwood serving in London as US naval attaché, where he acted as chief of staff to Admiral Ghormley.

Rear Admiral Lockwood entered front-line service on May 26, 1942 when he assumed command of the submarines operating in the Southwest Pacific. Initially, these boats operated from western Australia, but Japanese pressure in the Solomons and New Guinea caused a shift to bases in eastern Australia. During the summer and fall, Lockwood sent occasional long-range patrols into the South China Sea and off the Philippines. Although there were many targets, his submarines achieved few successes because of faulty torpedoes. Not until September 1943 were all of the problems fixed. After 21 months of war, Lockwood's submariners finally had an effective weapon.

When the commander of all the US submarines in the Pacific Fleet died in a plane crash, Lockwood replaced him in February 1943. He held this position until the end of the war. Lockwood made it a habit to personally greet newly commissioned submariners who joined his force. Along with a train of experts, he boarded the new submarine to meet its captain and to learn about any teething problems and new equipment and gadgets. Then he invited the captain to lunch. He employed a familiar style that made him popular with officers and men alike. He became known as "Uncle Charlie."

By early 1943, code breakers cracked the code used by the Japanese to direct their supply and merchant ship convoys and escorts. Henceforth, the Pacific Fleet's submarines utilized this information to sail directly to potential targets, thereby eliminating the need for long, fuel-consuming, and often fruitless searches. Still, submarine warfare remained a difficult enterprise. During 1943, decrypts directed submarines to over 800 potential targets. Submarines sighted only some 350, attacked about one-third of these vessels, and sank only 33.

Admiral Charles Lockwood was the most experienced American submariner. When he took command in Australia, his submarines were failing to achieve good results. They used the M-14 torpedo. It was an expensive, technical marvel equipped with a magnetic exploder. Because of its cost, the M-14 was never tested with a live warhead. Frustrated submariners reported that they seemed to miss their target repeatedly. Lockwood ordered tests and soon discovered that the torpedo's depth control mechanism was defective. At first, the Bureau of Ordnance refused to believe these results until Admiral King pressured the bureau into running its own tests, which confirmed the problem. The M-14 still suffered from faulty magnetic and contact exploders. The torpedo design did not compensate for variations in a ship's magnetic field caused by the ship's position on the earth's surface. Much more basic, the torpedo's firing-pin mechanism did not work. (National Archives)

"Uncle Charlie" Lockwood looks on while Admiral Nimitz shakes hands with a submarine crew. (National Archives)

Lockwood s force continued to grow. By July 1944, some 100 submarines operated from Pearl Harbor and another 40 from Australia. They carried the now reliable M-14 torpedo as well as an electrical torpedo that left no wake. By the year s end, about half of the Japanese merchant fleet, including replacements, and two-thirds of her tanker fleet, had been sunk. The submarines had closed the flow of oil from the East Indies to Japan and cut her bulk imports by about 40 percent. Overall, they accounted for over 1,300 Japanese ships, or some 55 percent of Japan's entire losses at sea. The cost to Lockwood's submariners was heavy; about one in five submariners who made war patrols failed to return.

A torpedoed Japanese destroyer photographed in 1942 through the periscope of an American sub. By the war's end, the Pacific Fleet's submarines had sunk an impressive number of capital ships, including a battleship, eight aircraft carriers, and 11 cruisers. National Archives)

Admiral Marc Mitscher, a master of carrier warfare, is shown here. (National Archives)

Lockwood retired as a vice admiral in 1947 and died 20 years later. Although little remembered, Lockwood deserves great praise for contributing to the success of the American submarine campaign in the Pacific.

Born in 1887 in Hillsboro, Wisconsin, Marc Mitscher graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1910. He was an average student whose wild escapades earned him the nickname "Oklahoma Pete." After serving on a variety of surface ships, Mitscher attended flight school in 1915 and qualified as a pilot the following year. Mitscher earned the Navy Cross in 1919 for piloting a flying boat across the Atlantic Ocean. His interwar service focused on the development of naval aviation. .After serving at several naval air stations and working on experimental aircraft, Mitscher was assigned to the US Navy's first carrier in 1926. That same year, he landed the first aircraft on the newly constructed giant carrier, the Saratoga.

Marc Mitscher's fleet endured punishing kamikaze attacks while operating near to the Japanese home waters. Here a Japanese "Zeke" (Zero) is shown on final approach against the battleship Missouri in 1945. (US Naval Historical Center)

In this faded and scratched but remarkable navy photo, a Japanese "Kate" torpedo bomber bores in toward the Hornet's island at center. At right is the splash of the torpedo that has just been dropped. It will hit the damaged Hornet and end any chance of saving her. (National Archives)

In July 1941, Mitscher was assigned to the new carrier, Hornet. He oversaw its commissioning and received promotion to rear admiral three days before war broke out. Mitscher's Hornet carried the B-25 bombers flown by the Doolittle raiders. As the Hornet passed beneath San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge on April 2, 1942, Mitscher announced over the Hornet's speakers, "This force is bound for Tokyo!" He commanded the carrier at the decisive Battle of Midway. After some land-based assignments, Mitscher took charge of all air units on Guadalcanal in April 1943. He led navy, army, marine, and New Zealand aircraft during the ensuing Solomon Islands campaign. In January 1944, Mitscher became commander of Carrier Division Three, which served with Admiral Halsey's and Admiral Spruance's Fast Carrier Task Force. He led the carrier attacks against the Marshall Islands. To support the invasion of Eniwetok, Mitscher's carrier task force attacked the Japanese base at Truk in February 1944. Historian, Ronald Spector, observes: "For a carrier task force to attack such a base unaided by land based planes ... would have seemed near madness a year ago. Yet Mitscher, masterfully handling his carriers its a single striking force, showed how easily it could be done." Mitscher's carriers sent 30 strikes against Truk, each of them more powerful than either of the two Japanese strikes against Pearl Harbor.

Mitscher's airmen enjoyed overwhelming success during operations around the Marianas Islands in the summer of 1944, in part because of the decline in the ability of Japanese pilots. More powerful US anti-aircraft fire also took its toll on the Japanese. A Japanese plane is downed while attacking the Kitkun Bay. (National Archives)

Admiral Theodore Wilkinson mastered the complexities of organizing and directing an amphibious invasion fleet. This type of job did not confer the same glory as a gun-to-gun duel or a carrier engagement, but it was indispensable to winning the war in the Pacific. (National Archives)

Promoted to vice admiral in March 1944, Mitscher commanded the carrier forces that raided the Marianas in June. The subsequent, overwhelming victory became known as the "Great Marianas Turkey Shoot." During this action, Mitscher's bold decision to turn on his ships' lights to guide his aviators back to safe night landings saved numerous lives. Under Halsey's command, Mitscher's carriers destroyed the Japanese decoy carrier force at the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944. His planes flew over Japan as a distraction from the attack on Iwo Jima. His forces completed the destruction of the Japanese surface fleet in the Battle of the East China Sea in April 1945.

Mitscher returned to Washington in July 1945, and received promotion to full admiral the following year. The strain of war had undermined his health. Mitscher died while C-in-C of the Atlantic Fleet in 1947. A modest leader, who avoided publicity, Mitscher was much respected by his men. In the words of historian Ronald Spector, he was "an inspiring leader [who] soon became the acknowledged master of the new carrier warfare."

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com