J. ARNOLD, S. SINTON, illustrated by DARKO PAVLOVIC

US COMMANDERS OF WORLD WAR II. NAVY AND USMC

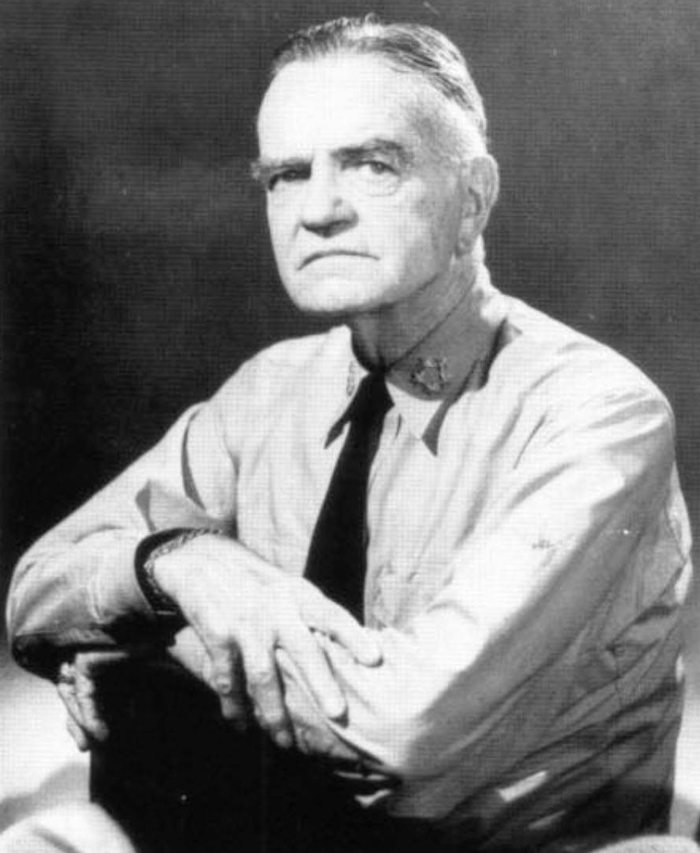

Thomas Hart was born in Davison, Michigan, in 1877. He graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1897. Hart led two submarine divisions to Europe in 1917. He graduated from the Naval War College in 1923 and the Army War College the next year. Hart gradually climbed the promotion ladder and became commander of fleet submarines from 1929-31. He held the prestigious assignment of Superintendent of Annapolis from 1931 to 1934. He next commanded a cruiser division and then became a member of the General Board from 1936 to 1939. His successful tenure, while holding a mix of important sea and shore duties, led to his promotion to admiral in July 1939.

Hart was in command of the small, aging Asiatic Fleet when the Japanese attacked the Philippines in December 1941. The Asiatic Fleet had never been intended to operate as a fighting fleet. Rather, its purpose was simply to show the flag. On the war's first day, Japanese bombers drove the fleet out of its main base in Manila Bay.

Admiral Hart inspects a Douglas SBD Dauntless on the flight deck of the Lexington. American carriers were unable to support Hart during his doomed defense of the Dutch East Indies. (National Archives)

Even though Hart had experience with submarines, the outbreak of war found his 22 submarines at sea inexplicably scattered. Neither they nor the surface elements accomplished much in the defense of the Philippines. Hart had built Manila into his fleet's major logistical center. MacArthur's decision to abandon Manila caught him by surprise and deprived the fleet of supplies, repair facilities, and communications. The day after Christmas 1941, Hart fled south aboard a submarine.

Because of his failure, Hart patriotically recommended that someone else assume command of the defense of the Dutch East Indies. Because he was present on the scene, Washington refused. Therefore, Hart next received the unenviable position of commander of naval forces for the American, British, Dutch, and Australian Command. He correctly doubted that the Dutch East Indies could be defended because of Japanese air superiority. He wanted to use his cruisers and destroyers for hit-and-run raids against Japanese convoys. The British wanted to use them to escort convoys to Singapore, and the Dutch to defend Java. Washington's efforts to manage operations from a distance added to the confusion. Hart supervised the successful destroyer action off Borneo on January 24, 1942. It marked the first time an American surface force had engaged since 1898. Still, Hart's pessimism angered some top American leaders and, more importantly, caused difficulties with the senior Dutch commander, Admiral K. W. Doorman. To placate Doorman, Hart was recalled to the United States "for reasons of health." He retired in July 1942 but was recalled to serve on the General Board. He did not see duty at sea again.

Hart retired again in February 1945 to accept appointment to a Senate seat. He held this position until the end of 1946 and died in 1971. During World War Two, fate had dealt Hart an enormously difficult task. He proved unequal to the challenge.

Born in Elizabeth, New Jersey in 1882, the son of a naval captain, William "Bill" Halsey graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1904. After sailing with the global tour of the "Great White Fleet" from 1907-09, Halsey began a 23-year tour involving destroyers, escort duties, and torpedo warfare. In 1917, he commanded a destroyer based in Ireland. After the war, he served as a naval attache in various European capitals. By 1927, Halsey sensed that the navy's future would be closely associated with air power. A vision impairment prevented him from becoming a pilot. Halsey finally qualified as a naval aviator in 1935 at the age of 52. Meanwhile, he had graduated from both the Naval War College and the Army War College. He commanded the aircraft carrier Saratoga from 1935-37 and rose to rear admiral the next year. The outbreak of war found him the senior carrier captain in the Pacific.

The aggressive Halsey supported Nimitz's strategy calling for carrier raids against Japanese bases. Halsey led the first US offensive in the Pacific, an attack against Kwajalein on February 1, 1942. This attack, and ensuing raids in early 1942 against Marshall, Gilbert, Wake, and Marcus islands, caused little damage but provided useful experience for the carrier task forces. Halsey's task force launched the B-25s that raided Tokyo in April 1942. Halsey was in hospital with a skin infection during the Midway campaign. He recommended that Admiral Raymond Spruance replace him.

Halsey replaced Ghormley as commander of the South Pacific Theater in October 1942. When sailors learned about the change in command they cheered wildly. Halsey went to theater headquarters in New Caledonia where, in the words of one historian, he "swept through Noumea like a tornado." At this time, the supply line supporting the marines on Guadalcanal was badly clogged. Halsey's energy galvanized the support troops and encouraged hard-pressed marines and sailors. To the ground commander on Guadalcanal, General Alexander Vandegrift, Halsey said, "Go on back [to Guadalcanal]. I'll promise you everything I've got." Halsey was true to his word. He made numerous decisions that aggressively placed his major surface units and scarce carriers at risk in order to win the fight for Guadalcanal. In November, at a time when many doubted the wisdom of committing two new battleships to the narrow waters around Guadalcanal, Halsey sent Willis "Ching" Lee with the battleships to intercept a Japanese relief force. Halsey believed that "he must throw everything at this crisis." He also, wisely, relied upon his subordinates' initiative, in this case giving Lee complete tactical freedom of action. For his victories during the Guadalcanal campaign, Halsey received promotion to full admiral on November 26, 1942.

During discussions about how best to continue the offensive, Halsey met with MacArthur. To everyone's surprise - both men had mercurial temperaments - the two leaders got along well together. Halsey commanded the offensive against the Solomon Islands throughout 1943 and into 1944. The American advance through the Solomons triggered a Japanese counter-offensive in November 1948. To defend the Bougainville invasion force, Halsey ordered a carrier strike against Rabaul. Since the early hit-and-run raids in 1942, carriers had avoided attacking strongly defended Japanese bases. Halsey knew that Rabaul was one of the strongest Japanese bases in the Pacific. He boldly ordered the raid to proceed. He later remembered, "I sincerely expected both air groups to be cut to pieces and both carriers stricken if not lost. (I tried not to remember my son Bill was aboard one of them.)" In the event, the raid was a stunning success. It demonstrated the power of carrier task forces and paved the way for subsequent, far-ranging operations.

Admiral William Halsey was the most aggressive senior US naval commander of the war. A typical Halsey message was sent to his commanders in the Solomon Islands on October 26, 1942 at a time when the fate of Guadalcanal hung in the balance: "Attack - Repeat - Attack!" His message electrified his combat elements. He also inspired men throughout his command with his injunction to, "Kill Japs, Kill Japs, Kill More Japs!" These words, in letters two feet high, hung over the fleet landing at Tulagi, across the water from Guadalcanal. When Halsey became famous, newspapers corrupted "Bill" to "Bull" to capture his thrusting nature, but no one who knew Halsey personally ever called him that. Halsey's aggressive nature served him well until the invasion of Leyte, when he uncovered the invasion beaches as he led his carriers after a Japanese decoy force. He later wrote that when informed that Japanese battleships would soon be loose in Leyte Gulf, "There was nothing I could do except become angrier." (National Archives)

From the summer of 1944 on, Halsey and Spruance shared active command of the carrier task forces. The idea behind this notion was that each admiral and his staff would have time to rest and plan after a major operation but that the ships themselves would stay in action. Even though his fleet had grown tremendously, Halsey retained his improvisational command style. A staff officer observed that under Halsey "you never knew what you were going to do in the next five minutes or how you were going to do it, because the printed instructions were never up to date ... [Halsey] never did things the same way twice."

Successful carrier operations against the Philippines convinced Halsey to advocate an early invasion of Leyte. He did not expect the Japanese fleet to intercede against the October 1944 Leyte landing. He was wrong. When his scout planes located the Japanese carriers, he did not realize that these carriers were bait designed to lure his own carriers away from Leyte Gulf. Halsey gobbled up the bait but carelessly left the San Bernardino Strait unguarded, thereby allowing Japanese battleships to attack the invasion fleet. Arguments over Halsey's action continued for years but it is evident to most observers including, at the time. Admirals King and Nimitz, that Halsey had blundered. In 1944 Halsey's enormous popularity with both sailors and the public protected him from punishment and from possible relief. Halsey made another controversial decision when he sailed his fleet into the teeth of a terrific typhoon in December. Three destroyers sank, with the loss of 800 sailors. Many historians have roundly criticized Halsey's judgment and management during this storm. Halsey's fleet provided air cover for the Okinawa invasion during July and August 1945. His last combat command involved attacks against the Japanese home islands. The Japanese surrender occurred aboard Halsey's flagship, the battleship Missouri.

Halsey's dynamic leadership bolstered morale during the difficult early war months. His aggressive style usually paid enormous dividends. He was guilty of inefficient, sometimes careless, administration. In spite of these flaws, Halsey emerged from the war as a highly respected leader who attracted fierce loyalty from his men. Halsey died in 1959.

Frank Fletcher was born in Marshalltown, Iowa, in 1885. He graduated from Annapolis in 1906 and received his commission two years later. His gallant participation in the Vera Cruz occupation in 1914 earned him the Congressional Medal of Honor. Fletcher commanded a destroyer during World War One. During the interwar years he held a variety of staff positions and graduated from both the Naval War College and the Army War College. Promoted to rear admiral in 1939, Fletcher served with the Atlantic Fleet as commander of Cruiser Division Three from 1939 to 1941.

When the Pacific War began, Fletcher commanded the effort to relieve Wake Island. However, he had never before led carriers. Consequently, the relief effort was badly bungled. The high command at Pearl Harbor ordered Fletcher to turn back from Wake Island as its American defenders foundered. Although some members of Fletcher's staff argued that he ignore the recall, Fletcher dutifully obeyed orders. In the words of navy historian Samuel Eliot Morison, "the failure to relieve Wake resulted from poor seamanship and a want of decisive action."

Frank Jack Fletcher was an admiral of the old school who had trouble adjusting to fast-paced, carrier warfare. His orders for the May 1942 battle in the Coral Sea were to "destroy enemy ships, shipping and aircraft at favorable opportunities in order to assist in checking further advances in the New Guinea-Solomons area." Given that he commanded only two carriers, such daunting orders would have challenged anyone. In the event, Fletcher proved reluctant to utilize his radio intelligence and made several tactical blunders. Nonetheless, his planes sank the first Japanese carrier of the war - the American pilot jubilantly radioed, "Scratch one flattop" - and gave the first check to the Japanese advance in the Pacific. (National Archives)

Fletcher commanded the carrier task force that intercepted the Japanese thrust into the Coral Sea in May 1942. This confused fight was the first sea battle in history fought entirely by air. Although the Lexington was lost, Fletcher's carriers repulsed the Japanese and prevented them from moving against Port Moresby, New Guinea. Next came the decisive sea battle of the Pacific War at Midway. As he steamed into position near Midway, Fletcher faced an enormous responsibility. At Pacific Fleet headquarters, an analyst noted, "The whole course of the war in the Pacific may hinge on developments of the next two or three days." On June 3, 1942

Fletcher received reports that search planes had found the main Japanese fleet. He correctly judged the reports to be wrong and instead trusted his intelligence reports regarding the more likely location of the Japanese carriers. He also correctly judged that the Japanese had no idea that his carriers were in the area. When, the next day, search planes did find the enemy carriers, Fletcher ordered an attack. Fletchers aviators sank four Japanese carriers. The Japanese managed to damage Fletcher's flagship, Yorktown, so severely that Fletcher had to transfer to the heavy cruiser Astoria. The Yorktown later sank. Still, the four-to-one exchange rate was hugely favorable to the Americans.

Fletcher showed that he had learned from his experience at the Coral Sea and did well at the Battle of Midway. Promoted to the rank of vice admiral, Fletcher next took charge of the impending counter-offensive in the Solomons. When he met with the principal commanders to discuss the operation, Fletcher was openly skeptical. Worse, he had a public row with Admiral Richmond Turner, the newly arrived commander of the transports and cargo ships that were to land the marines at Guadalcanal. Having lost the Lexington at Coral Sea and Yorktown at Midway, Fletcher was afraid to risk his three remaining, priceless carriers, particularly if they had to operate within range of Japanese land-based aircraft. Consequently, Fletcher announced that he would keep his carriers within supporting range of the landing forces for only two days, half the time needed to land all the troops and supplies. In the event, Fletcher abandoned the marines 12 hours earlier than even he had planned, claiming that he was short of oil and weak in fighter planes. He retired without authorization from his superior. Admiral Ghormley. Turner and the marines felt this desertion unwarranted. Historians have concurred, exposing Fletcher's claims about oil and fighters as flimsy excuses to hide his real concern: his unwillingness to risk his carriers.

Sudden bursts of brief, intense combat characterized carrier warfare in the Pacific. A battle's outcome could hinge upon the precise location of a bomb strike. For example, had the bomb that hit Fletcher's Yorktown at Coral Sea struck 20 feet toward her centerline, thereby damaging her flight deck instead of penetrating the comparatively unused lee of her island, she would have been disabled for Midway. Here, a Japanese dive-bomber descends on the Hornet at the Battle of Santa Cruz while a torpedo plane approaches from the left. (US Naval Historical Center)

Based upon intelligence reports about another major Japanese operation in the Solomons, on August 23, Fletcher's carriers were operating about 150 miles from Guadalcanal. The next day he received contact reports and hurried his carriers, including his flagship Saratoga, to intercept the Japanese. At the ensuing Battle of the Eastern Solomons, the war's third great carrier engagement, he hurled most of his air power against the first target his scouts detected. His planes sank a Japanese light carrier, a ship the Japanese had designated as "bait." This left the enemy's two fleet carriers intact and able to retaliate. However, Fletcher showed that he had learned from previous battles and retained 53 fighters for combat air patrol over his carriers. A ferocious aerial combat took place, with the Enterprise absorbing three bomb hits. Thereafter, both sides cautiously withdrew. Overall, Fletcher's handling of this battle was timid, but because the Japanese were even more cautious and had lost a carrier, the Americans could claim victory. Admiral Nimitz observed, "The Japanese had shot their bolt and with air forces seriously reduced were retiring." For the next two months, both sides sought to reinforce Guadalcanal and a naval war of attrition ensued. Fletcher's flagship Saratoga was torpedoed on August 31 by a Japanese submarine. Fletcher himself received a wound.

After the Guadalcanal campaign, the high command, responding to widespread criticism of Fletcher's performance as a carrier task force commander, reassigned him to command of naval forces in the North Pacific. He held this position from 1943 until the war's end. After the war, he became Chairman of the General Board until his retirement in 1947. He died in 1973.

Fletcher possessed unquestionable personal courage. However, he was unable to adjust to the stress of fast-moving carrier warfare. The loss of Lexington at Coral Sea and Yorktown at Midway made him extra cautious during the Guadalcanal campaign. Nonetheless, Fletcher commanded the carriers that gave the Japanese their first important check, at the Battle of the Coral Sea, and was in charge of the vessels that turned the tide of battle in the Pacific at the Battle of Midway.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1886, Raymond Ames Spruance graduated 25th in his class from the US Naval Academy in 1907. He sailed in the global voyage of the "Great White Fleet" in 1907. Thereafter, he followed a typical career trajectory that did not include any combat duty. His specialty was gunfire control. His most uncommon service before World War Two involved three tours of duty at the Naval War College. In July 1941, Spruance assumed command of the Pearl Harbor- based cruiser squadron. The outbreak of war saw this unit assigned as a surface screen for Admiral Halsey's carrier forces. Spruance learned a great deal by observing Halsey in action. When Halsey, in turn, realized that he was too sick to command during the Midway campaign he recommended that Spruance replace him even though Spruance was not an aviator. In May 1942, Spruance assumed command of Task Force 16 aboard the carrier Enterprise.

Spruance immediately plunged into the pivotal Midway campaign. On June 4, he received orders from Admiral Fletcher to attack the Japanese carriers. Spruance initially intended to launch his strikes at 0900 hrs., when his planes would be only some 100 miles from the enemy. Upon learning of the Japanese early morning raid on Midway, Spruance revised his plan. He decided, on the basis of advice from his chief of staff, to attack two hours earlier. This meant his planes would risk running out of gas and probably result in the loss of planes and pilots. Nonetheless, Spruance judged it an acceptable risk because the possible reward was to catch the enemy carriers in the act of refueling their planes on deck. In addition, Spruance decided to launch even' available plane, "a full load," retaining only enough fighters for a combat air patrol over his own carriers. Spruance's calculated risk worked brilliantly. His planes did strike at a time when fuel lines, bombs, and ammunition were strewn about the Japanese flight decks. His divebombers fatally damaged three Japanese earners in their first strike, turning the tide of battle in the Pacific War.

Spruance's performance at the Battle of Midway justified his appointment. He had wisely used his available forces to help win this decisive action. His cool, calculated tactics overshadowed the performance of his superior, Admiral Fletcher. Two weeks later came promotion to chief of staff of the Pacific Fleet and subsequent assignment as a deputy to Fleet Commander Admiral Nimitz. In this capacity, he helped plan the offensive into the Central Pacific. In August 1943, he assumed command of this offensive, supervising the invasion of the Gilbert Islands. The American earner task forces now dominated the Pacific. Spruance demonstrated this fact when he led a raid against the formidable Japanese base at Truk in February 1944. Thereafter, he directed the invasion of the Marianas.

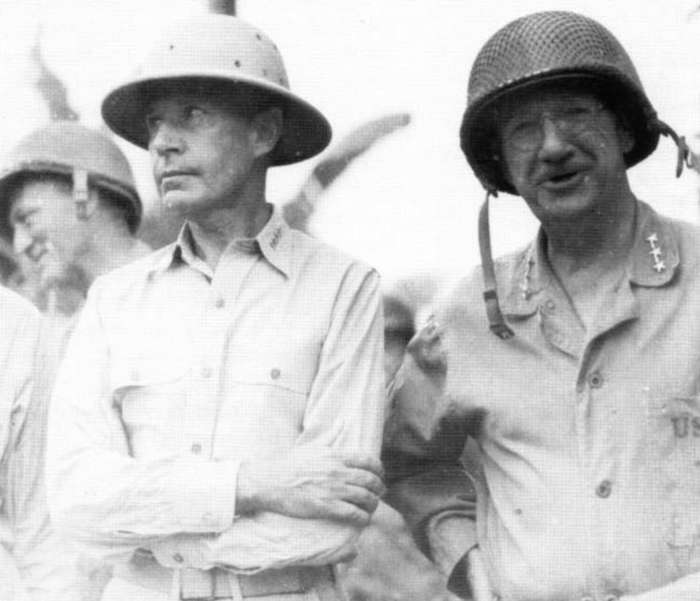

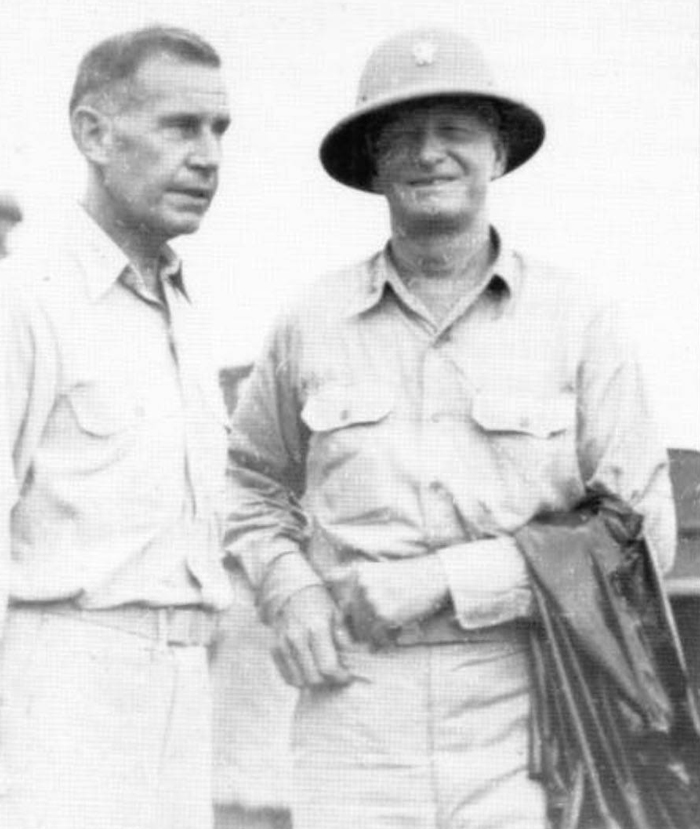

Admiral Spruance (left) on Saipan, is standing next to Marine General Holland Smith (National Archives)

At the decisive Battle of Midway, Admiral Raymond Spruance (on left, standing next to Admiral Nimitz) performed superbly. He maintained a clear picture of the rapidly changing tactical environment and judiciously listened to advice from his staff to boldly seize the chance to strike the Japanese carriers when they were most vulnerable. According to naval historian, Samuel Eliot Morison, "Spruance emerged from this battle one of the greatest fighting and thinking admirals in American naval history." (National Archives)

During the Marianas campaign Spruance's Task Force 58 virtually annihilated the last of the Japanese carrier-borne air fleet. However, he also had a chance to destroy the Japanese surface fleet. Instead, he cautiously avoided using his battleship force in a night engagement. In the words of an American after-action report, "The enemy had escaped ... we could have gotten the whole outfit! Nobody could have gotten away if we had done what we wanted to do." Throughout the war, Spruance held a healthy respect for Japanese fighting prowess. In this case, his respect may have been misplaced. During subsequent operations, Spruance participated in a unique command arrangement. From the summer of 1944 on, when Spruance assumed active command, his force was known as the 7th Fleet. When Halsey commanded the same vessels, it was known as the 3d Fleet. The idea behind this sharing of command was that each admiral and his staff would have time to rest and plan after a major operation but that the ships themselves would stay in action. Spruance was in command during the invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. He was planning the invasion of japan when the war came to an abrupt end.

In November 1945, Spruance superceded Nimitz as Commander-in-Chief Pacific Fleet. He was appointed President of the Naval War College in February 1946 and held that position until his retirement in the summer of 1948. He served as Ambassador to the Philippine Islands from 1952 to 1955 and died in 1969.

Spruance's cautious, methodical command style contrasted with Halsey's impulsive, risk-taking approach. An officer who served with both admirals observed that whereas Halsey improvised and did not utilize up-to-date printed instructions, Spruance relied on printed instructions "and you did things in accordance with them." In Nimitz's words, "Halsey was a sailor's admiral and Spruance was an admiral's admiral." The cool, aloof Spruance inspired respect but not love.

Because he eschewed publicity, he never received the popular acclaim accorded to other officers. Among naval historians, Spruance is regarded as a great commander. Many claim him to be "the most brilliant fleet commander of World War Two."

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com